Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

It was 1961, and LaVerne Bell-Tolliver was terrified. She had just entered seventh grade at Forest Heights Junior High in Little Rock and was the only black student to do so.

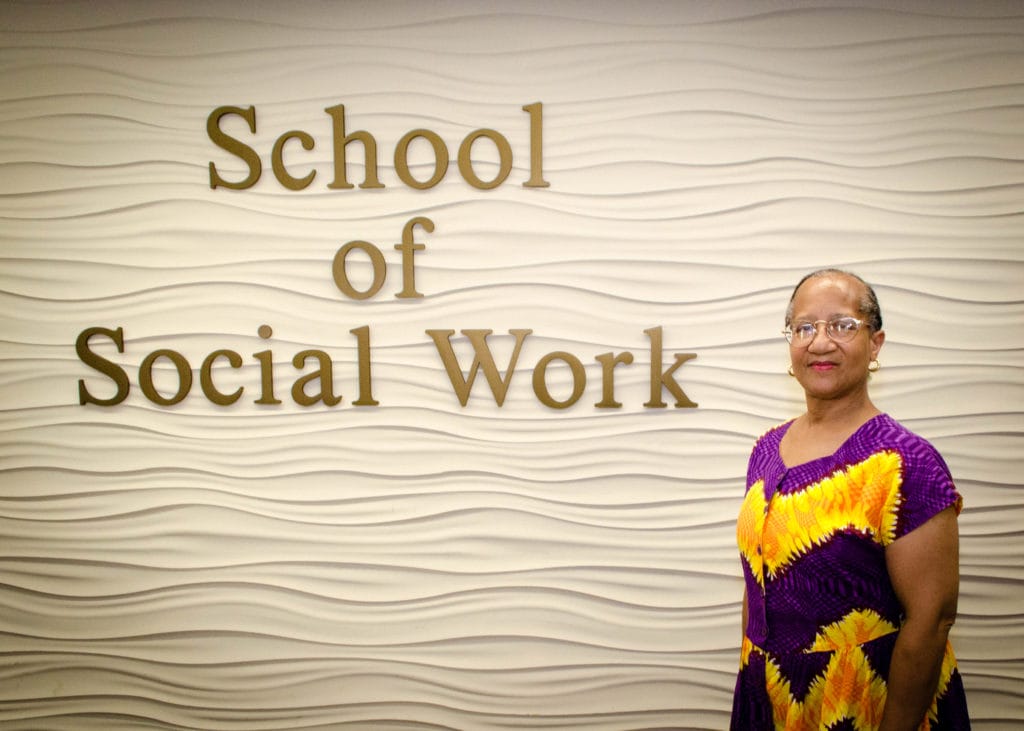

Throughout her time at the school, she often was ignored and isolated. No one sat with her at lunch or during assemblies. Her self-esteem was low, and by ninth grade, she had developed ulcers. Bell-Tolliver, who is now an associate professor of social work at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, later learned the school board had selected 25 young black students to be the first to desegregate Little Rock’s junior highs—East Side, Forest Heights, Pulaski Heights, Southwest and West Side—in the early 1960s.

As an adult, she had unanswered questions. How did the selection process take place? What happened to those students? What was their experience like? In 2014, she set out to interview those students, and their experiences can be read in her book, “The First Twenty Five: An Oral History of Little Rock’s Public Junior High Schools,” which released Feb. 1.

“It is very isolating to be the only student of color in a school,” said Bell-Tolliver, who believes her grades and citizenship records likely contributed to her being selected. “Given the fact that Forest Heights was in a wealthy area, [children of wealthy parents] attended that school. I did experience some isolation or people who ignored me during that time.”

Bell-Tolliver was originally supposed to attend her junior high school, which is now Forest Heights STEM Academy, with one other black student whose parents withdrew her before the school year began. Desegregating a school—especially alone—was not something Bell-Tolliver wished to do. Two other black students joined the school when she reached ninth grade.

“We had a ninth-grade picnic, but the principal called me in to determine if I was going to go,” Bell-Tolliver said. “While it was OK for me to go, I needed to know the location was segregated, which is kind of astounding. There were those kinds of things that still stick out.”

For her book, Bell-Tolliver traveled across the country to interview 18 of the 25 students (Those who were not interviewed are mentioned in the book). Among those interviewed was Katherine Bell, Bell-Tolliver’s sister, who attended a different junior high and whose experience was not shared with Bell-Tolliver until the interview process.

“Some students really, really wanted to attend [their school], and they would do it again even though they experienced hardships,” Bell-Tolliver said. “What also surprised me was that one student dropped out of Southwest and one student attended alone for the next two years, and I didn’t learn that until I started interviewing the person. One person attended grades eight and nine alone. I think they designed some of the schools to not be successful.”

In junior high, Bell-Tolliver learned that although some students spoke to her inside the classroom, they would not acknowledge her when class was over. Forest Heights only allowed those enrolled to attend school functions, so she couldn’t invite her black friends to school dances if she wanted. This all worsened her experience at the school.

In her interview process, she learned that one student faced more aggression at his school due to being a male and that at other schools that had more than one African-American enrolled, students still felt alone. Some black students had a couple of teachers who were nice to them, but for the majority, that wasn’t the case. Many teachers witnessed violence done by other students and “turned their backs and did nothing.”

“From the systemic standpoint, children need to have teachers and administrate staff who genuinely care even though the expectations are high,” said Bell-Tolliver, whose self-esteem was so low then that she believed she was one of the poorest students there. “My sister and [another] young lady both talked about the fact that they did not encounter anyone who expected them to excel. These were students who had done well in school, and they were, in some cases, not being challenged to that extent to be able to excel.”

Looking back, she believes she performed as well, if not better, than other students. At the time, when students had to take their report card from teacher to teacher to receive their grade, one instructor gave Bell-Tolliver a mark lower than she earned.

“My home-ec teacher made me march back to that class and tell [that teacher] to put the right grade back on there,” she said. “Of course, that was not comfortable.”

It was hard for Bell-Tolliver to fit in and learn how to interact socially in such an environment as a preteen. But that experience also helped shape her into who she is today.

“On the other hand, I’ve come to understand how to [navigate] adverse conditions and to stand up under pressure that many people are not able to handle,” she said. “There are some deep issues pertaining to others [and] they still impact me to some extent.”

At programs this month in recognition of the book launch, some of the former students featured in the book were present to discuss their desegregation experience. Bell-Tolliver said the experiences of those former students aren’t exclusive to the past and we can learn to treat one another better.

“People are still experiencing being different in some kind of way, relating to race and ethnicity and even disability,” she said. “As many times as people come to me years later and say, ‘I’m sorry. I wish I had done such and such.’ That could be the greatest kindness of all if you’re kind in that moment.”

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Syd Hayman

It’s no secret that Arkansas contains beautiful nature, charming cities...

What is now a well-respected vegan-friendly establishment with a variety...

In December 1977, year-old choir Art Porter Singers performed George...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment