Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

When it comes to economic empowerment, Al Bell has walked the walk.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, the North Little Rock resident led Stax Records, a soul music record label second only to Motown in sales and influence. The Memphis-based label signed and promoted musical titans like Otis Redding, Isaac Hayes and The Staple Singers. In later decades, after Stax closed, Bell worked with Prince to release the smash single, “The Most Beautiful Girl in the World,” and created a label which produced hits like Tag Team’s “Whoomp! There It Is.” Adapting business lessons gleaned from his godfather, former Arkansas governor Winthrop Rockefeller, Bell has reached pinnacles of success in his 78 years most Americans will never see.

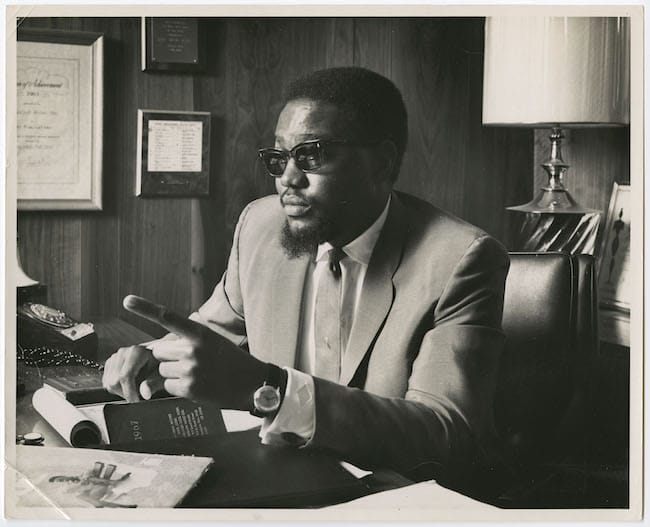

Al Bell the Maverick: Courtesy of Stax Museum of American Soul Music

Yet the goal of a more equitable society has long weighed on Bell’s mind — even more so when he thinks of his relationship with Martin Luther King, Jr. King was assassinated 50 years ago on April 4 in Memphis while denouncing America’s involvement in the Vietnam War and advocating for better pay and working conditions for Memphis sanitation workers — part of a “Poor People’s Campaign” for Americans of all colors. In 1967, King had said: “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.”

Bell knew King for nearly a decade, he told more than 100 people last week in a panel at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. As a teenager in the late 1950s, he was working as a teenage disc jockey in Little Rock. One of his Scipio Jones High English teachers, Virginia Robinson, directed his attention to Rev. King who was then leading civil rights protests focused on uplifting African Americans. Mrs. Robinson urged Bell to join the activist Southern Christian Leadership Conference King had helped found.

So, in 1959, Bell moved to Georgia to attend SCLC leadership workshops and become a student teacher. “I learned more about what Dr. King was about, which at that time was more passive resistance seeking equal rights. But what was at the core of Dr. King’s [ideology] was economic development and economic empowerment.” Those core goals resonated with Bell, the budding entrepreneur.

Watch the Crystal Bridges talk with Al Bell and Dr. Mark Anthony Neal, a professor at Duke University:

The nonviolence stuff, though, was more of a challenge. Especially during the time Bell was on the front lines of a march in Savannah, singing “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around.” He recalled an especially virulent white man in the crowd “calling me all the kinds of names you could think of.” Then, as he got within four feet, the man spat on him. “Before I knew it, I was out of my pocket with my switchblade knife, going through all these people after this man,” Bell recalled, chuckling. “Hosea Williams and Ralph Abernathy came after me, but I lost complete control and broke up the march,” Bell said in 2005.

That night, King reemphasized to Bell what passive resistance meant. King said: “Many of us are gonna be killed, they’re gonna hang us, dogs are gonna bite us and we’re gonna have to take all of that,” Bell recalled at a recent Rhodes College panel. “What’s important about it, is that they’re gonna carry it on television… People will realize outside of America that we even exist in America as a people, and they will see how America is treating us. Then, after that’s done, you can go about the business of talking about economic development and economic empowerment — which is what got him killed.”

Dr. Mark Anthony Neal on left and Bell on right at Crystal Bridges

Bell graduated from Philander Smith College in 1961 and moved to Memphis, where he starred as a radio DJ for WLOK. He honed his flair for promotion with sign-offs like this: “This is your 6 feet 4 bundle of joy, 212 pounds of Mrs. Bell’s baby boy, soft as medicated cotton, rich as double-X cream, the women’s pet, the men’s threat, the baby boy Al” — and then he rang a bell — “Bell.”

He joined Stax in 1965 and quickly ascended the ranks, working on the business and production sides. He continued to cultivate regional talents who elevated the label into the world’s foremost exporter of soulful sounds with a raw, gritty edge. Meanwhile, the nation grew more polarized as American casualties in Vietnam skyrocketed. That war’s economic costs had stifled some of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s earlier efforts to alleviate poverty, so Martin Luther King and the SCLC began planning a massive, multi-racial march on Washington D.C. to ignite mass support for an economic bill of rights. “It didn’t cost the nation one penny to integrate lunch counters,” King said in February 1968. “But now we are dealing with issues that cannot be solved without the nation spending billions of dollars and undergoing a radical redistribution of economic power.”

Specifically, the Poor People’s Campaign sought:

– A $30 billion annual investment in antipoverty measures

– A government commitment to full employment

– Enactment of a guaranteed income

– Funding for the construction of 500,000 affordable housing units per year

Around this time, Bell said he truly began to fear for King’s life. For years, the FBI — behind the urging of its director J. Edgar Hoover — had spied on King, planting false stories in the media and among activists to destroy his credibility and paint him as a communist sympathizer. In 1964, agents sent King an anonymous letter urging him to commit suicide, according to Newsweek and the final report of the 1975 U.S. Senate Church Committee. In January 1968, Hoover, without notifying the White House, ordered FBI field offices to volunteer for a new secret operation coded POCAM (for “poverty campaign”), “designed to stop King in a specialized thrust of the FBI’s COINTELPRO against ‘Black Nationalist/Hate Groups,’” historian Taylor Branch wrote in “At Canaan’s Edge.”

Bell’s concern grew when he learned more white people than black people were signing up for the D.C. march, scheduled for later spring 1968. “That bothered me,” he told the Crystal Bridges crowd. King “could go to Washington with a million black folks, and they could handle that — no big deal. But you come in there with a million white folks and 250,000 black folks — that’s a problem.”

Bell believed a majority-white movement would have signaled a widespread desire to overthrow the government. King “was waking up another group of citizens in America who realized ‘Hey, we’ve got a problem: We’re not being treated fairly.’” In “making that kind of move, they had no other alternatives but to eliminate him.”

At 6:01 p.m., April 4, 1968, a single bullet through the jaw and neck dropped King on the balcony of Memphis’ Lorraine Motel. The preponderance of evidence points to James Earl Ray, an escaped convict, as the shooter. Ray pleaded guilty in 1969 and avoided the death penalty. The case closed, but he quickly afterward filed a motion to withdraw his plea, claiming he’d been coerced by his attorney and the FBI. In jail, he maintained his innocence for decades. Many in King’s family, too, believe Ray was framed as part of a larger conspiracy.

King’s sudden death loosed torrents of grief, bitterness and civil strife across our nation. It also opened an ongoing opportunity, especially on anniversaries like these, to practice listening, understanding and healing. Presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy stressed this hope in perhaps his greatest speech, given only minutes after learning of King’s death.

For Bell, music provided a path to healing. Before the shooting, Bell wanted to tell King to take time off and reduce his public presence before something terrible happened. He said he chose to communicate this with a song delivered by singer Shirley Watson: “Send Peace and Harmony Home.” Originally, “I didn’t mean to the spiritual world. I just thought he should take a sabbatical.”

On April 4, they were recording it in the studio. The feeling wasn’t quite there, though, Bell recalled. After eight or ten takes, Stax songwriter Homer Banks “opened the door and shouted ‘Dr. King got shot and killed!’ as the tape was rolling. Shirley started crying and singing, and we got the essence of ‘Send Peace and Harmony Home.’”

[NOTE: The singer’s name is “Shirley Watson,” not “Walton” as misspelled in the YouTube video]

Al Bell At Stax Header Photo: Courtesy of Reed Bunzel

Arkansan Evin Demirel often writes about cultural heritage. He highlights other Scipio Jones High School alumni in his book “African-American Athletes in Arkansas: Muhammad Ali’s Tour, Black Razorbacks & Other Forgotten Stories.”

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

One response to “Al Bell and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Last Days”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

[…] Print Page […]