Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

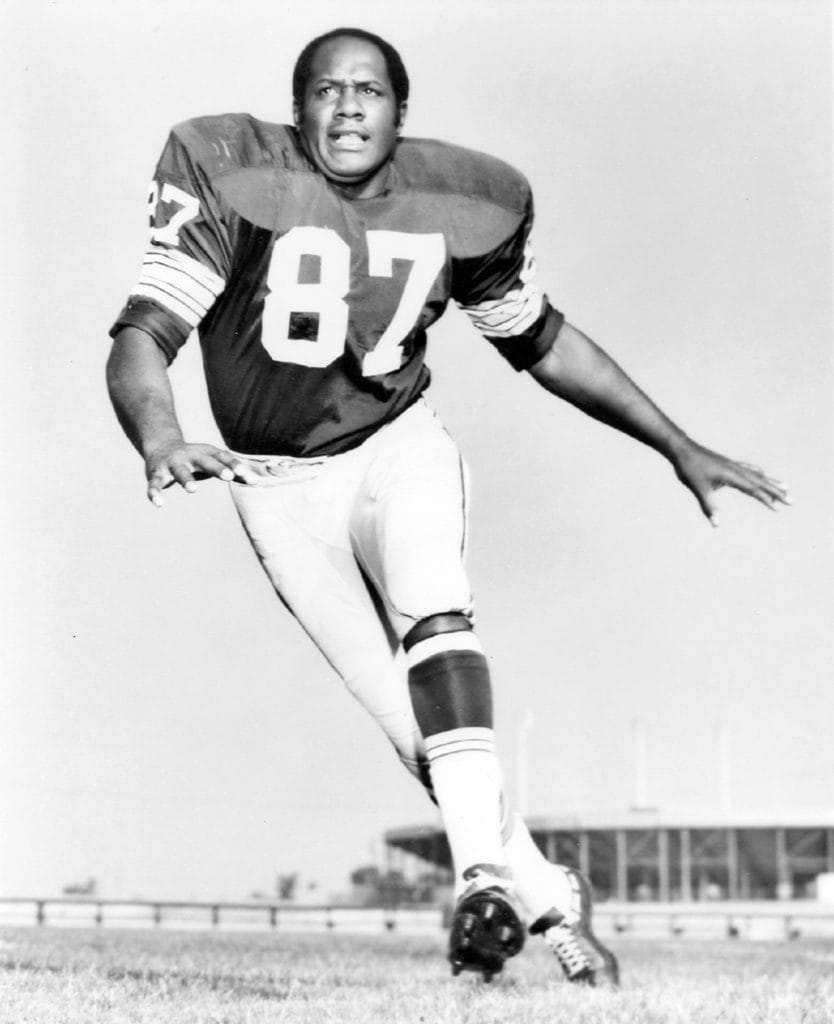

Arkansans don’t have their own NFL team, but they have nonetheless played a significant role in the nation’s most popular sports league. Fifty years ago, a handful of native Arkansans fueled the success of the first Super Bowl champions and in the process helped propel a still partially segregated United States into a more meritocratic society. One such Arkansan was Conway County native Elijah Pitts, a former star at the historically black Philander Smith College in downtown Little Rock.

On January 15, 1967, Pitts scored two touchdowns in the first Super Bowl — then dubbed the NFL-AFL Championship Game — in a Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum which had 30,000 seats left empty. Its halftime performance featured a couple universities’ marching bands and a local high school drill team. “I never thought the Super Bowl would become what it is,” he later told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette’s Jim Bailey.

From relatively humble beginnings, the annual game has evolved into a commercial bonanza with halftimes that now showcase the world’s most famous entertainers. During Super Bowl 50, it was Beyonce’s turn, and her performance created a stir.

By contrast, the racial makeup of the Super Bowl teams themselves sparked no public debate. African Americans accounted for 68% of the Denver Broncos’ and Carolina Panthers’ starting players. A mostly African-American NFL, where blacks and whites alike have equal shots at starting jobs, is the NFL most fans know.

Arkansans like Pitts and Travis Williams, an El Dorado native who joined the Packers in 1967, deserve credit here. As a rookie Williams became one of the most electrifying kickoff returners the game has ever seen. In nine games in 1967, Williams returned four kickoffs for touchdowns with an average return of 41.1 yards — a single-season NFL record which still stands. The season ended with another title. That Packers team, featuring three African-American Arkansans, punctuated a 7-year run of five Green Bay NFL championships in all.

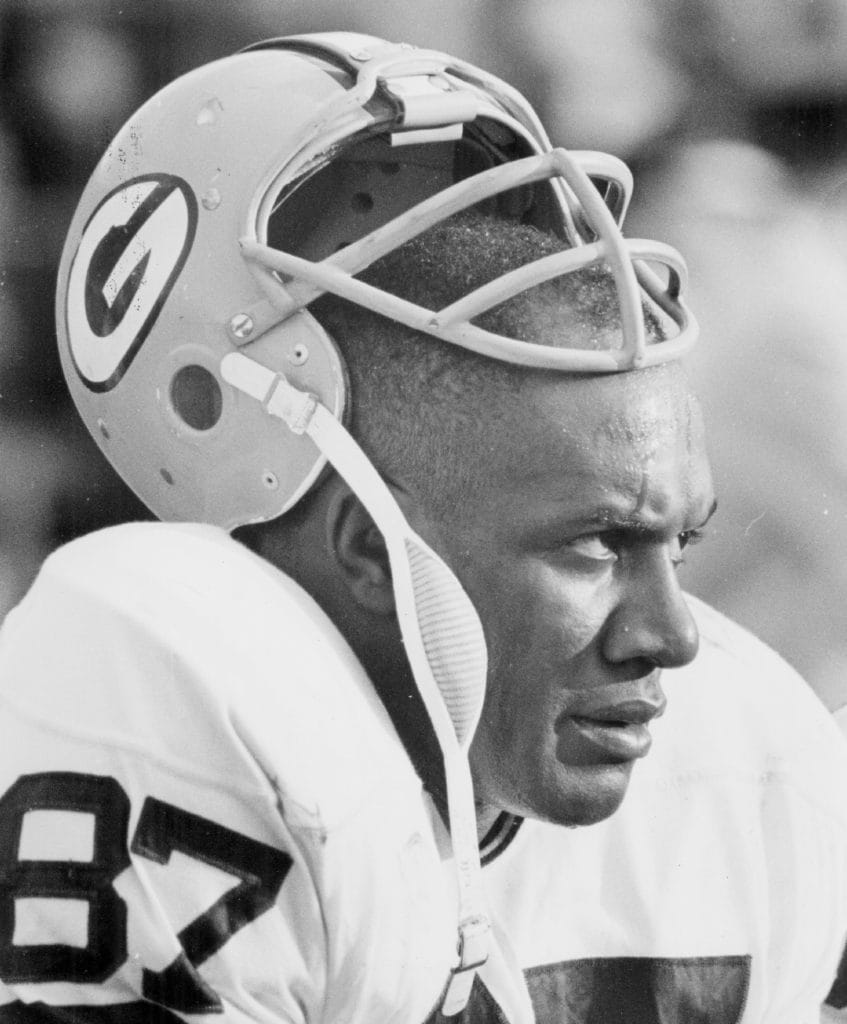

“Our success probably helped diversity in the league more than anything,” said star defensive end Willie Davis, also an Arkansan native. “The rest of the league knew they had to keep up.” Davis spent his early years in Hot Spring County before moving just over the state border to north Louisiana. He starred at two all-black schools: Booker T. Washington High School in Texarkana, Ark. and then Grambling State University.

Green Bay’s 1967 edition included 13 African American Packers. Eight years earlier, when Packers coach Vince Lombardi had arrived, the roster had only one. The east Wisconsin town had seven black male residents in all, WISports.com’s Jay Sergi wrote. A year later Davis joined the team. “They had no idea about black people except for what they saw on TV, which at the time was even more negative in its representation of the black community,” he wrote in his memoir Closing the Gap. “They had no real life experience with black people out here, and they were perplexed and fascinated by us.”

Willie Davis, photo courtesy of the Green Bay Packers

Davis recalls the more white locals and black players learned about each other, the more the walls came down. “‘Maybe all those things I heard about you people aren’t true,’ was a rather common phrase I heard in the beginning,” he recalled. Pretty soon, Green Bay natives embraced their black Packers as much as their white Packers.

“They all wanted to be our friends. I can’t tell you how many times I had a beer bought for me or how many times bar or restaurant patrons argued to see who could sit next to me,” Davis recalled. “What I found these people wanted to talk about was their love for the Green Bay Packers.”

No doubt, most fans also admired Vince Lombardi, whose longstanding refusal to allow skin color to alter his assessments of players’ true abilities started paying major dividends. While the Civil Rights Act of 1964 mandated widespread integration in American society at large, the Packers’ success had a similar effect within the narrow confines of pro football. “It was as if the owners took a look at Coach Lombardi’s formula and said ‘Hey, I gotta get some of those (African-American) players!,” Davis told WISports.com. “Pretty soon, all the teams opened up shop, allowing all positions on their teams to be earned by the best competitors.”

Lombardi, who believed prejudice against his Italian-American heritage cost him earlier job opportunities, helped speed a widespread social change already underway. “He treated us as equals, just players competing for a spot on the team,” Davis said. “He chose not to see color in an era where most coaches chose to look the other way in terms of blacks.”

This is Part 1 of a two-part series OnlyInArk.com is running to celebrate African-American Arkansans’ contributions to the sports world. Stay tuned for Part 2. The author has started two projects to honor Arkansas’ African-American sports of heritage here and here.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Evin Demirel

In the big three team sports, the Razorbacks have produced only two...

This season, the Arkansas Razorbacks are doing things no Hogs basketball...

Beasting isn’t a term normally reserved for women basketball players,...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment