Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

Baseball Hall of Famer Bill Dickey was born in Bastrop, Louisiana, on June 6, 1907, an irrelevant inconvenience for one of the most honored men in Arkansas baseball history. The family moved to Kensett, Arkansas, when Bill was a child. Technically an adopted son, Bill Dickey’s name is indelibly associated with Arkansas baseball. Ask anyone in Arkansas, William Malcolm Dickey is from White County, Arkansas!

Dickey’s father was a railroad man who had grown up playing on semi-pro teams in Tennessee, and he passed his love of the game down to his sons. Bill’s older brother, Gus, played on semi-pro teams around the Dickey family’s new home, and his younger brother, George, would eventually spend 13 seasons in professional baseball.

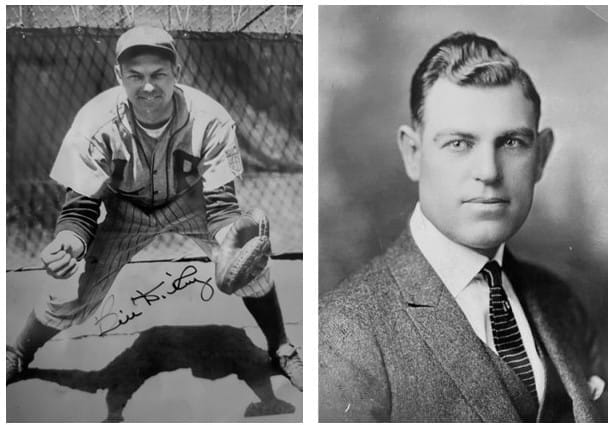

In the Kensett, Arkansas, of the early 1900s, Sunday baseball was the weekend entertainment. Dickey played on the men’s town team as a teenager and later starred at nearby Searcy High School. In the fall of 1924, at age 17, he enrolled at Little Rock College. The following summer, Little Rock Travelers manager Lena Blackburn spotted the teenager catching in a semi-pro game. By the end of the summer of 1925, eighteen-year-old Dickey was a professional baseball player, wearing the uniform of the Little Rock Travelers.

Dickey bounced around the Travelers organization with moderate success as a hitter, but he was baffled by the intricacies of catching. Looking back at the first few years of his career, Dickey classified himself as a “lousy catcher.” Fortunately, he ran into a mentor who may have rescued his career.

Facing a cash flow dilemma typical of minor league baseball in the early 20th century, Little Rock sold its promising young catcher to the Minneapolis Millers in the American Association. The Millers immediately farmed the struggling catcher down to Muskogee in the Western League, where Little Rock’s Ray Winder was the general manager. Winder immediately recognized a teenager in a career crisis, but the Muskogee executive’s expertise was not catching skills. He had something else to offer Bill Dickey.

Dickey would later explain, “[Winder] sat down and talked to me like a father.” The general manager convinced his young catcher that he had what it took to be a big-leaguer, but it would not be easy. “Why don’t you give it a year at least? You have played for less than a month.”

Dickey went to work on his skills, and, with Ray Winder as his personal career counselor, he was soon on the right track. Two seasons later, he found himself in the World Series with his teammates Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

Over his 17 seasons as a member of the New York Yankees, Bill Dickey became the standard by which major league catchers would be judged in the first half of the 20th century. By his first full season in New York, Dickey was the everyday catcher for the most prestigious team in baseball, the New York Yankees. In 1928, at age 22, the young man from rural Arkansas was playing baseball in the bright lights of New York with Babe Ruth.

Dickey batted .324 in his first full season and .339 in 1931, but the Yanks failed to get back to the World Series until 1932. The Yankees won the 1932 series, with four straight victories over the Cubs. Although Ruth, Gehrig, and the other more outgoing Yankees got most of the headlines, Dickey batted .431 in his first World Series. It was not his performance on the field that moved the quiet county boy to the headlines, it was the uncharacteristic move he made shortly after the World Series ended.

On October 6, 1932, the Arkansas Gazette ran a bizarre headline at the top of the sports page. America was in the midst of the Great Depression, and baseball owners, already known for frugality, cherished every dollar that they did not have to relinquish to player salaries. Despite the fiscal hard times and tightfisted big-league ownership, the Little Rock paper announced, “Bill Dickey Signs Lifetime Contract.”

Despite his obvious value, no baseball player—not Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, or the Yankees’ young catching star—was going to be guaranteed a lifetime baseball contract. The clever headline referred to Dickey’s marriage to a New York showgirl named Violet Arnold. Bill Dickey would never avoid the limelight again.

While he was becoming a headliner off the field, Dickey continued to improve as a baseball player. The Yankees were moving toward a remarkable period in their history, and Bill Dickey had assumed a prominent place with the Bronx Bombers.

After finishing second for three consecutive years from 1933 to 1935, the 1936 Yankees began a period of success never before achieved in major league baseball. From 1936 to 1939, the Yanks won four straight World Series. Only once during that period did their World Series opponent win two games in the Fall Classic.

Dickey made the All-Star team each year during the Yankees’ unprecedented championship run. Now playing on a team led by Hall of Famer Joe DiMaggio, Dickey batted better than .300 each of the four seasons, finishing in the top six each year in the Most Valuable Player voting.

New York’s World Series run came to an end in 1940. The Yanks fell to third place after the retirement of Lou Gehrig, whose battle with ALS became a symbol of courage that emerged as the poignant back story to his Hall of Fame career.

The Yankees would win two more World Series in 1941 and 1943 with Bill Dickey as their All-Star catcher. In 1943, he batted. 351 as a 36-year-old, but after two years in the military and recurring knee problems, he retired in 1946.

Dickey returned to Little Rock and managed the Little Rock Travelers to a last-place finish in the Southern Association. The hapless Travs won 51 games. Dickey would later admit that he quickly realized managing would not be his future career choice.

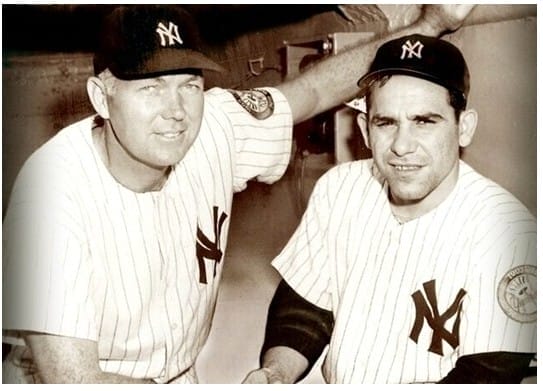

Managing might not have been Bill Dickey’s forte, but he did have a future in baseball, and, thankfully, the Yankees had a new and better idea of his value. In 1949, a new Yankees leadership team, general manager George Weiss and manager Casey Stengel, coaxed Dickey to return to New York and mentor their new catching prospect. The Yanks were pretty sure the struggling young fellow called Yogi from the “Hill” neighborhood in St. Louis had unlimited potential. By the late 1940s, the “lousy catcher” of those dark days in the 1920s was the standard by which all big-league catchers were judged. The young catcher enthusiastically welcomed his new coach. According to Yogi Berra, Dickey’s role would be, “Learnin’ me his experience.”

After his return to the Yankees, the quiet, unassuming Dickey also appeared in his second motion picture. He had been cast in the 1942 story of Lou Gehrig’s life called The Pride of the Yankees. In 1949, Dickey appeared in The Stratton Story, an inspirational story about an injured pitcher, Monty Stratton. Although acting seemed far from his skill set, he was uniquely capable of playing Bill Dickey in both films.

Dickey would remain as a coach and special catcher whisperer for the next nine seasons, beginning as Yogi’s mentor and ending his career as Elston Howard’s catching counselor. To his collection of eight World Series rings from his playing days, he added six more as a coach. In 1954, during his time as a coach in New York, Dickey was chosen as the fourth catcher to be enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Dickey Stephens Park

After retirement in 1957, Dickey returned to Arkansas, where he remained until his death in 1993, splitting his time between work with the Stephens Investment Company in Little Rock and his fishing/hunting home on Lake Millwood. In 1959, he was chosen for the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame as a member of the organization’s first induction class. Dickey-Stephens Park, home of the Arkansas Travelers, is named in honor of Bill Dickey, his brother George, and benefactors Witt and Jack Stephens.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Jim Yeager

In 1942, the Americans Tom Brokaw would later celebrate as our...

In 1920, the winter days between Christmas and New Year’s Day promised...

The 1951 baseball season arrived in Little Rock with little cause for...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment