Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

Trains revolutionized the United States in the 1800s. People and goods could now cross states in hours rather than days. Railroad towns sprang up as tracks were laid to connect cities. The first track hit the ground in 1858, connecting West Memphis to Madison. The Civil War quickly ended progress, but after the Civil War ended in 1865, Arkansas focused on laying track across the state. In 1866, only 271 miles of railroad track existed in Arkansas. By 1900, over 3,000 miles of track had opened the state up to rail travel.

Trains didn’t just enable the transport of people and goods in larger numbers than ever before; they also offered the criminal element a nearly irresistible opportunity.

Train robberies exploded across the Midwest and West, giving rise to notorious gangs like the Younger Gang, the Reno Gang, and the most famous of them all, Jesse James. While these violent acts led to loss of property and even death, a romanticized notion of train robberies fired the imaginations of towns along the tracks and fueled the flames of fame. Perhaps it was the dual lure of fame and easy riches that led to Arkansas’s most notorious train robbery.

On Nov. 3, 1893, Train 51 of the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railway left Poplar Bluff, Missouri, on its usual run down to Texarkana and Little Rock. Many passengers were returning from the World’s Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair. It included marvels such as the first Ferris wheel and the “White City,” a series of temporary buildings built in a neoclassical style to host the fair’s 200 exhibitions. Over 27 million people visited the fair in its six-month run.

These fair-goers were making their way back to Arkansas and to places further south on Train 51, which was due to arrive in Little Rock that night. The day grew cold and dreary. Rain fell as the seven-car train chugged through Missouri into Arkansas. They stopped for dinner at Walnut Creek and resumed the journey to Little Rock. Around 10 p.m., the train made a scheduled stop on a sidetrack at Olyphant, with a population of 50, to allow the Cannonball Express to pass by. This name was given to many trains that made fast, nonstop runs.

As Train 51 sat motionless on the sidetrack, conductor William McNally, who had worked this route since the early 1880s, leaned out of the car, waiting for the all-clear lantern signal from the baggage attendant. Instead, the sound of gunshots burst through the cold night. The baggage attendant shouted to McNally that they were being held up. McNally wasted no time. He ran to the passenger cars to warn everyone to hide their valuables, and asked to borrow a gun from a passenger. He took the gun to the front of the train, where he fired into the darkness at the bandits. When they returned fire, a bullet hit McNally and killed him.

The robbers, wearing bags and black masks, relieved the passengers of $6,000 in cash, jewelry and other valuables. The entire robbery and the death of the conductor took place in under 20 minutes. The robbers disappeared into the darkness surrounding Olyphant, and passengers placed McNally inside the train and continued to Little Rock.

Word traveled fast, and by the time the train pulled into Little Rock, a posse had already gathered and left shortly after for Olyphant. Ten sheriffs organized posses over the next week and joined the search for the train robbers. William McNally had been a well-known and beloved figure on the railroad for many years, and his death spurred on the search effort. The railroad offered a $300 reward, and Arkansas Governor William Fishback added his own $100 reward for each robber.

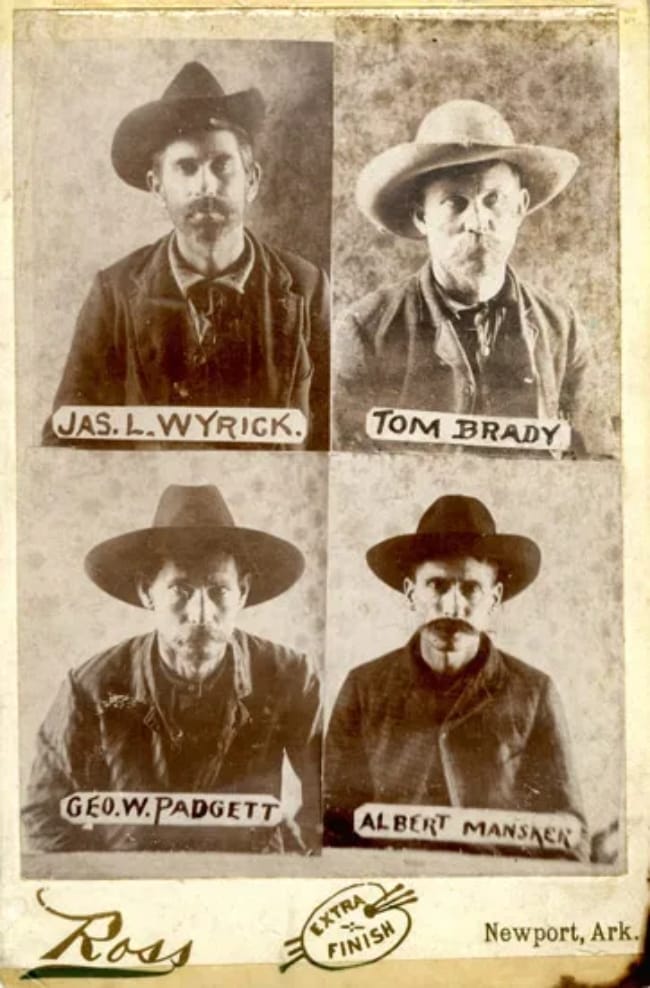

The next few weeks captivated the entire state. The Arkansas Gazette detailed manhunts and many suspects as posses canvassed the state, resulting in many false accusations and arrests. However, four suspects were eventually arrested: Tom Brady, Jim Wyrick, Albert Mansker and George Padgett. The men hadn’t fled the state; instead, they stayed close to their homes. They were not seasoned train robbers. Instead, the men had met in Indian Territory while smuggling whiskey and hatched a plan to rob a train. George Padgett, a former Little Rock policeman, rode Train 51 and discovered the ideal time to rob the train, when it stopped to allow the Cannonball Express to pass by.

After being arrested, Padgett turned witness against the other men, accepting a delayed trial as his reward. The trials for Brady, Wyrick and Mansker took place in January 1894. Each man denied their involvement in Conductor McNally’s death. Each man insisted that George Padgett was the mastermind behind the robbery. They all agreed that they had consumed a lot of whiskey before the train robbery to find their courage. Wyrick even claimed he lost his courage, despite the alcohol, and never took part in the crime. The juries disagreed with those claims of innocence. All three men were convicted of murder and sentenced to death by hanging.

On April 7, 1894, the three men were hanged in Newport, with a photographer covering the event and later selling photos. Before the execution, the men were allowed to speak and proclaimed they did not kill William McNally to the end. The Arkansas Gazette also covered the trial and execution in detail. George Padgett was never tried for his part in the robbery. The judge ordered his release, and he walked away from the robbery and the execution of his fellow robbers, a free man.

Four other men were also implicated in the robbery, but three were never tried and the fourth, Pennyweight Powell, was acquitted in July 1894. The Olyphant train robbery was the last in the state.

Never again did Arkansas experience a train robbery that captivated the entire state with its daring, tragedy and pursuit of justice.

Still shots and film posters of “The Great Train Robbery” are in the public domain, preserved through the Library of Congress.

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

One response to “The Olyphant Train Robbery in Arkansas”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

There is a Padgett Island close to Newark and not far from Olyphant; I wonder if George was related to those Padgett’s.