Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

Memorial Day is synonymous with the beginning of summer. We celebrate by hitting the water, cookouts and a lot of family time over this long weekend. However, Memorial Day originated as a day to remember those who died while serving their country in the military. For veterans and their families, it certainly bears a greater weight as they remember their times of service and comrades they lost. Today we look back on the stories of four Arkansas veterans who served in World War II.

Clarence “Foots” Lay

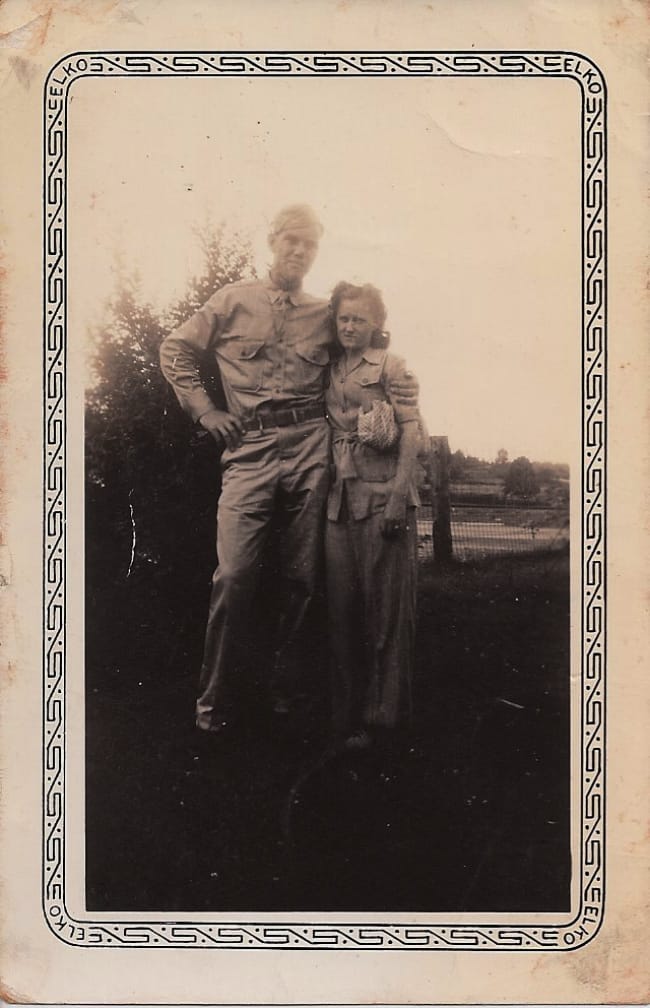

Clarence “Foots” Lay was living in Wickes, Arkansas when he was drafted in April 1942. He reported to Camp Crowder, Missouri for basic training. Camp Crowder trained the Signal Corps inductees and Foots became a messenger for the 98th Signal Battalion.

In early 1943, the battalion shipped out to New Guinea. The journey by sea took 28 long days. The soldiers spent that time playing poker, swapping stories and constantly scanning the sea for periscopes. Japanese submarines patrolled the waters on the hunt for any Allied vessels. When a periscope was spotted one day, Foots says it nearly gave everyone on board a heart attack, but the periscope belonged to an Allied sub warning the ship away from a nearby Japanese convoy.

Once the 98th landed on New Guinea, they established a message center, which included radio and telephone operators as well as messengers. Foots recalls that they had no transportation yet so he delivered his messages by foot. Once the engineers established roads on the island, he drove a jeep.

Foots delivered messages all over the island, to infantry units, anti-aircraft units and the Air Force. Near the end of the war, he hand-delivered a message to General Douglas MacArthur. MacArthur called Foots into his office and chatted with him before he wrote a reply to the message and gave it to Foots to deliver to the original sender, General Crouger.

The meeting deeply impacted Foots and it was one of the few war stories he liked to share for the rest of his life. Foots was discharged in December 1945 and returned to Arkansas, where he reunited with his wife, LaVerne. They moved to Mena and Foots worked at Itasco and always enjoyed fixing just about anything that was broken.

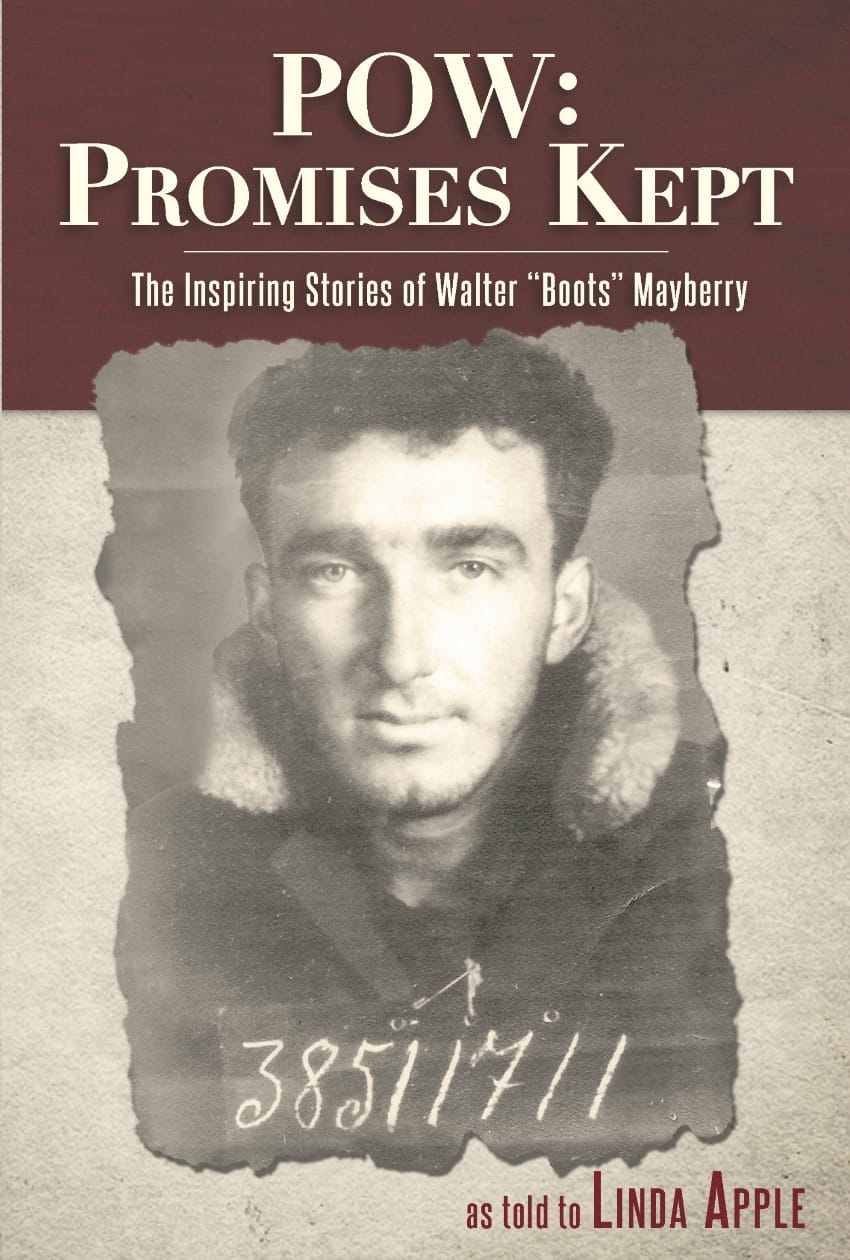

Walter “Boots” Mayberry

Walter “Boots” Mayberry was inducted into the Army Air Force on July 16, 1943. He was 18 years old and fresh off of high school graduation. Since he’d always been a good shot, he went to gunnery school, then army aircraft school. In November 1944, he and his crew were assigned to a new B-17 bomber and sent to the European Theater. Boots joined the 388th Bomb Group in Knettishall, England. Boots went on his first mission in December 1944. In Boots’ word, “that first mission was a disaster.” The oxygen system on board the B-17 failed and they had to return to their base still carrying 5,000 pounds of explosives. To top it off, the crew didn’t get credit for the mission.

The bombing missions Boots participated in were massive campaigns into Germany that consisted of 800 to 1,000 bombers along with 500 fighters to protect the bombers and skirmish with any German planes in the area. Each plane carried around 5,000 pounds of explosives and dropped their loads on major cities in Germany. The damage was staggering.

As a gunner, Boots fired a few times at attacking German fighters, but the concern that haunted their missions was the anti-aircraft fire the bombers encountered as they drew near their targets. On Boots’ last mission, his worst fear was realized. As his B-17 approached Nuremberg on February 20, 1945, the anti-aircraft fire was intense. A burst hit the right wing of the bomber and it immediately caught fire. The pilot tried to put the fire out by diving from 28,000 feet to 13,000. Then he ordered his crew to bail out.

Boots kicked open the escape hatch door. The tail gunner scrambled toward the hatch first but hesitated to jump. Boots took one look at the fire outside the plane’s window and put his boot on the gunner and pushed him out before he jumped himself.

The men hadn’t received much instruction on how to operate their parachutes. When Boots jumped, he was falling headfirst through the air. When his chute opened, it jerked him up and broke several vertebrae in his neck, which paralyzed his hands and left him unable to steer the chute. He drifted through wreckage and aircraft fire, helpless. A P-51 fighter plane spotted him and circled around Boots as he floated down, trying to protect him from further attacks. The last time the pilot circled, he saluted Boots.

Boots landed in an open field prepared for plowing. German civilians working in the field immediately surrounded him. He was taken to jail and spent ten days in solitary confinement before he was sent to Frankfurt to a larger interrogation camp. Then he was transferred again to a POW camp in Moosburg with 80,000 to 90,000 Allied POWs. This was Germany’s largest POW camp. When it was liberated on April 30, 1945, that estimate jumped to 110,000 Allied POWs.

The POWs suffered through air raids, hunger and forced labor. They could see the smoke from Dachau’s chimneys. General George S. Patton visited the camp shortly after its liberation and Boots saw one of the most famous generals in the war. Boots was flown to France, where he finally received medical care, food and new clothes. He traveled back to the U.S. in June on a convoy ship. When he reached New York, he was able to call his mother in Pine Bluff, who only knew her son was missing in action, not that he was still alive and free from the POW camp.

He was awarded a brief visit home before he had to report to Miami to learn how to fly a B-29 bomber. The war was still raging in the Pacific. Boots never had to participate in bombing Japan though. After the war ended, he returned to Stuttgart, Arkansas and eventually was discharged in December 1945. During his time of service, Boots earned three bronze stars and a purple heart. Walter “Boots” Mayberry’s full story is chronicled in the book POW: Promises Kept.

Oscar McCain Kimbrough

Oscar McCain Kimbrough joined the army in 1940, before the U.S. entered World War II. He was in the National Guard during college. Once he graduated, he was stationed in the Aleutian Islands as a 2nd lieutenant, thanks to his participation in the guard. As part of the army in Alaska, Oscar would have experienced what is called the Williwaw War, a mostly forgotten part of World War II, though many Arkansas soldiers actually served in the Aleutian islands for part of the war.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Oscar was sent to Belgium as part of an artillery unit. Oscar’s family cites that he rarely spoke of the war once he arrived home, but by happenstance, they learned of one story highlighting Oscar’s bravery. The man who recounted the story was one of the men in Oscar’s unit and he told the following story.

Oscar’s artillery unit was assigned to protect a strategic bridge. His unit needed to install an artillery piece at a high vantage point over-looking the bridge to fend off any German attacks against it. The installation would take place at night, and Oscar, as an officer, asked for volunteers from the men in his unit to help carry the artillery to the vantage point. One of the volunteers is the man who related Oscar’s story to his family.

The men set off at night pushing a heavy artillery gun on wheels. The route they took was a mined railway that wound through a mountain pass that held enemy snipers. The mission had to be carried out silently and completely in the dark. The men pushed and pulled the gun over the railroad ties. Oscar carried a hooded lantern to scout for mines. When he spotted one, the men would lift the wheels over the mines.

The journey up to the vantage point took them all night, but they made it without detection and set up their artillery. They were able to save the bridge from destruction, which allowed the Allied armies to cross over and mount an offensive against the German forces. The soldier telling the story added that Oscar was a brave man and a great officer and he would have followed him in combat anywhere.

After the war, Oscar attended dental school on the G.I. bill and continued to serve in the National Guard. He moved to Springdale, Arkansas in 1951 to set up his dental practice and raise a family. He also served 20 years in the Guard and achieved the rank of major. Oscar hardly ever spoke of his service in the war, but fortunately, his story of heroism came to light through one of his dedicated men.

Robert B. Patterson

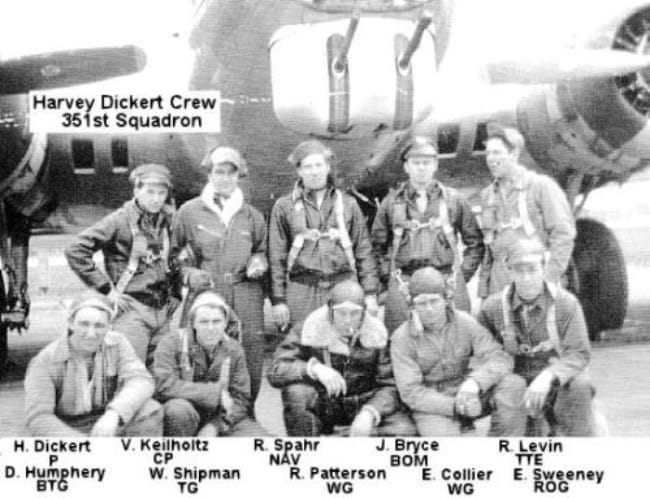

Immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Robert B. Patterson signed up for the draft in Floris, Oklahoma. He wasn’t inducted into the army until the spring of 1943, though. He was assigned to 351st Bomb Group of the Army Air Corps in Salt Lake City, Utah, where he trained as a waist gunner. His crew flew a B-17 bomber and eventually received orders to head to England. They were stationed in Diss, England. Robert flew on 23 missions before his bomber was shot down. His crew participated in the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944. Robert remembers seeing the ocean below the bomber filled with thousands of ships traveling so close together it ‘looked like you could walk across them.”

Robert’s plane came under fire on April 10, 1945. The wing caught fire so the crewmates kicked the door open to jump, but the damage to the plane caused them to be thrown out. Five of the crew escaped, including Robert, but five others died. Even though Robert’s parachute opened, he sustained ligament damage to his ankles when he landed. He couldn’t walk and he was stranded in Germany.

“I crawled 20 miles on my hands and knees, playing hide-and-seek with the Germans,” he recounted years later. Finally, a German civilian pumped water for him and pointed down the hill toward a village where there were white squares painted on the roofs of buildings. Someone had just recently painted over the swastikas, and they were now aide stations for Allied wounded.

Fortunately, some Russian soldiers and a French officer came to his aide and carried him the rest of the way. From there, an ambulance took Robert to a hospital. On the ride, Robert was able to see the ruins of the places he had bombed and found the experience unbelievable.

Robert returned to England on a troop plane, and then to the U.S. Two of his surviving crewmates visited him at the hospital in the U.S. Later, he was able to reunite with the other two crew members. Both had been captured after bailing out of the plane and been POWs. To Robert, their stories made his own harrowing journey seem like nothing.

Robert never wanted to be considered a hero for the time he served. Despite the loss of five of his crewmates and his injuries, he would do it all again, saying, “It seems like we had more to gain in that war.” Robert returned to Siloam Springs, Arkansas, where he’d lived since he was 9 years old. Like many in his generation, he made a living with his ability to do almost anything, from carpentry to plumbing and electrical wiring, all while running a small farm on the side.

The stories of these four Arkansas World War II heroes are extraordinary, yet also just four among the many amazing stories of service and heroism among American servicemen and women. As you celebrate Memorial Day this year, take the time to remember the sacrifices many Arkansans have made over the years and thank them for their service.

Thank you to the Kimbrough family, Gayle Mourton, Kyra Franz and Edie Balmer for sharing these stories and photos with me. The photos are used with permission.

Flag Raising on Iwo Jima courtesy of the National Archives, Joe Rosenthal, Associated Press, February 23, 1945. 80-G-413988

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

One response to “A Celebration of Arkansas World War II Heroes”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

These are amazing stories…amazing men. I’m proud to know that each of these men are Arkansans, and am incredibly grateful for the life that I am able to have today because of the courage and strength they led with back then. I wish I could say two things, especially, to them: thank you, and welcome home….