Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

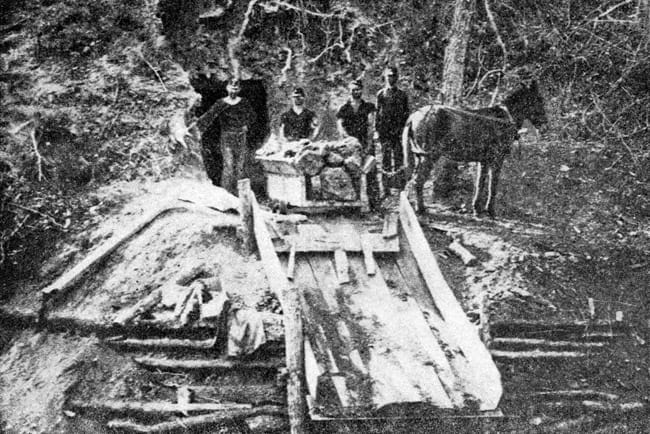

Coal mining is often associated with Appalachian states like Pennsylvania and West Virginia, but Arkansas also has a history of coal mining. In some Arkansas communities, coal mining and the danger and politics that surrounded it loomed large and affected the lives of many workers and families.

Millions of years ago, prehistoric swamps covered parts of Arkansas. When the vegetation in these swamps died, they were covered in mud and compacted into carbon and hydrocarbon to become coal. People have used coal as a source of heat and energy for many years. China had a coal mine in operation over 3,000 years ago. The Romans also used coal after discovering it in British coal fields, although there is no record that they mined the resource. In the United States, coal mining began in 1701 with a mine in Virginia.

The first mention of a coal mine in Arkansas was in 1818, so knowledge of this natural resource existed even before statehood. Coal deposits lie in the Arkansas River Valley, spanning six counties: Franklin, Johnson, Logan, Pope, Sebastian and Scott. These coal deposits run 33 miles wide and 60 miles long and are classified into different coal beds. While at least 25 coal beds have been identified, four of them have been mined: Upper Hartshorne, Lower Hartshorne, Charleston and Paris coal beds.

The first recorded coal mine opened in 1840 at Spadra (the Encyclopedia of Arkansas notes the center of coal mining as New Spadra to distinguish it from the original Spadra, which was a government-organized trading post between settlers and Native Americans.) Although coal was mined before the mine in Spadra, it was mostly from shallow beds that could be reached from the surface. Much of Arkansas’s coal doesn’t run very deep, with most beds not reaching more than ten feet in depth. The mine at Spadra was used to fulfill the needs of blacksmiths who used coal to fire their forges. Some of that coal was also loaded on barges to ship downstream, but in 1840, eleven barges sank, and all of that coal was lost.

In the 1840s and 1850s, it was also difficult to transport large amounts of coal away from the mines. Until railroad lines were pushed into Arkansas, coal mines in Arkansas largely served local needs. That changed in the 1870s. The Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad extended its line in 1873, making it possible to transport coal from the Coal Hill mines located in Johnson County. Four years later, the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway built a line into Fort Smith, and coal mining in Arkansas suddenly exploded. From 1880 to 1920, Arkansas hit its heyday in coal production. Coal took the top spot in Arkansas’s production of minerals and fuel.

This success didn’t come without controversy or sacrifice. Coal mining is dangerous, and finding people willing to work in the dark and dangerous conditions was a dirty business, too. Convicts first fulfilled the need for workers in the coal mines. Leasing convicts for labor outside prisons was a common practice in Arkansas in the 1800s. Labor companies paid the state for convict labor. This system was notoriously corrupt, and the convicts were mistreated. An investigation into the Coal Hill mining camp in 1890 by a legislative committee found the convicts lacked adequate housing, food and hygiene facilities and were often subject to physical abuse.

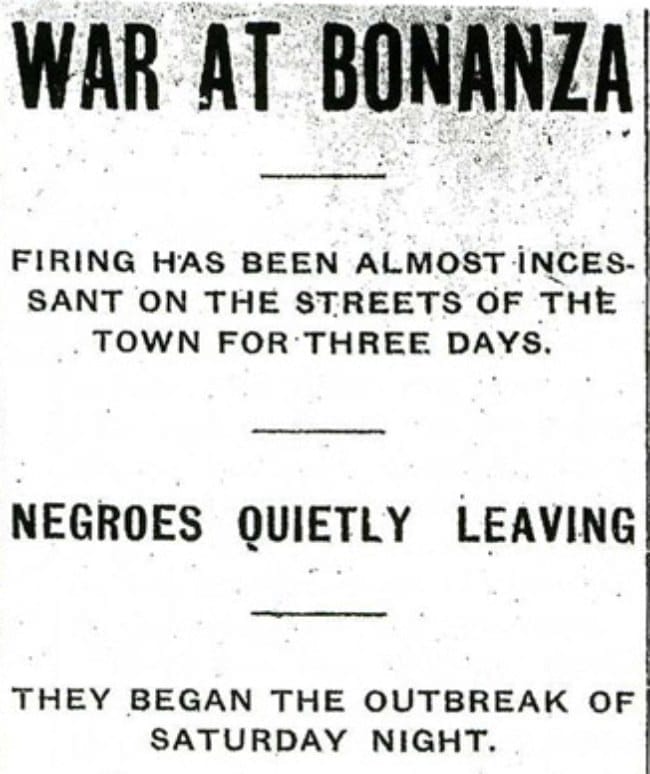

The practice of leasing convict labor finally ended in 1912 with Governor George Donaghey. With one cheap source of labor abolished, coal mining turned to new immigrants, mainly from central Europe. During this time, the industry experienced upheaval centered around labor unions. The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) started organizing in Arkansas in 1898. When they called their first labor strike in 1899, the coal mines hired Black workers to replace union workers. This practice continued for several years. The unions resented this and struck back by discriminating against Black workers. In 1904, the situation exploded in the Bonanza Race War.

In Bonanza, Sebastian County, the Central Coal and Coke company had three mines and the town was the center for business in the surrounding area. On April 30, white citizens held a union meeting and passed a resolution to force all Black citizens from the town. Two days later, the UMWA issued its own resolution, claiming not to be behind the expulsion order and pledging support for Black workers. Still, violence erupted, with several incidents of shots fired around town. Many of these were aimed at the homes of Black citizens, and mobs warned Black workers and their families to leave town. Many listened and fled the area.

Bonanza wasn’t the only town in Sebastian County affected by violence stemming from the coal mines. Fort Smith businessman Franklin Bache, who also owned out-of-state non-union mines, tried to open a non-union mine in the county in 1914. He hired non-union workers and armed guards to protect them from organized attacks from union workers. That didn’t stop UMWA workers from gathering on the morning of April 6 at Prairie Creek Coal Mining Company. Interestingly, in the middle of this conflict was a young female journalist, Freda Hogan, also a known Socialist and women’s rights activist. Hogan spoke to the workers, along with others, before they went to the mine. The situation escalated quickly once the workers confronted the armed guards. Soon over 1,000 union coal miners had forced their way into the mine, run off the non-union workers, and shut it down.

Tensions escalated. Bache had restraining orders placed on union leaders, and union members held a strike in one of Bache’s other mines. Both groups also prepared for more violence by accumulating weapons. Hogan continued to cover the conflict through speeches and newspaper articles. A judge issued an injunction against the union, which allowed Bache’s mine workers to return. Sporadic fighting broke out in Frogtown, a mile from Bache’s mine, and then at Bache’s mine. This conflict resulted in the death of two of Bache’s workers. The mine was ruined and other mines were later destroyed with dynamite. While the union seemingly had driven the only non-union mine out, the union’s grip had been broken, and other non-union mines began to open in the state.

This might have impacted the industry more if oil hadn’t already started to supplant coal as an energy source. Coal production fell in Arkansas after its peak year of 1909. By 1922, oil had edged coal out of its top spot in Arkansas’s mineral and fuel outputs. Production decreased over the next 30 years. By 1967, Arkansas only produced 189,000 tons of coal. In 1909, that number was 2,400,000 tons. Today, Arkansas doesn’t have any active coal mines. The last mine closed in 2017. Many mines were abandoned after they closed, with the possibility of acid drainage occurring in some of these mines. This happens when mined rocks combine with surface water to create a highly acidic solution filled with toxic metals like copper and iron. This can drain into the water table and contaminate it with toxic chemicals.

In 2023, Arkansas was awarded nearly three million dollars in Abandoned Mine Land (ALM) grants from the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement. These funds will help the state reclaim abandoned coal mines and address any environmental hazards the mines present.

While coal mining in Arkansas is now part of Arkansas history, two memorials commemorate coal workers’ contributions to the area. The city of Altus has a memorial of a bronze coal miner with the names of 500 coal miners who died in Arkansas mines engraved on pillars. The Coal Miners’ Memorial in Greenwood features a statue of a coal miner, a coal cart, and a wall engraved with the names of coal miners who worked in Sebastian County.

Header photo by Apphim via Wikimedia Commons.

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

One response to “A Rocky Past: Coal Mining in Arkansas”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

My grandfather worked in the coal mines there in the 1940s. He then moved his family to California for a better,safer occupation.