Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

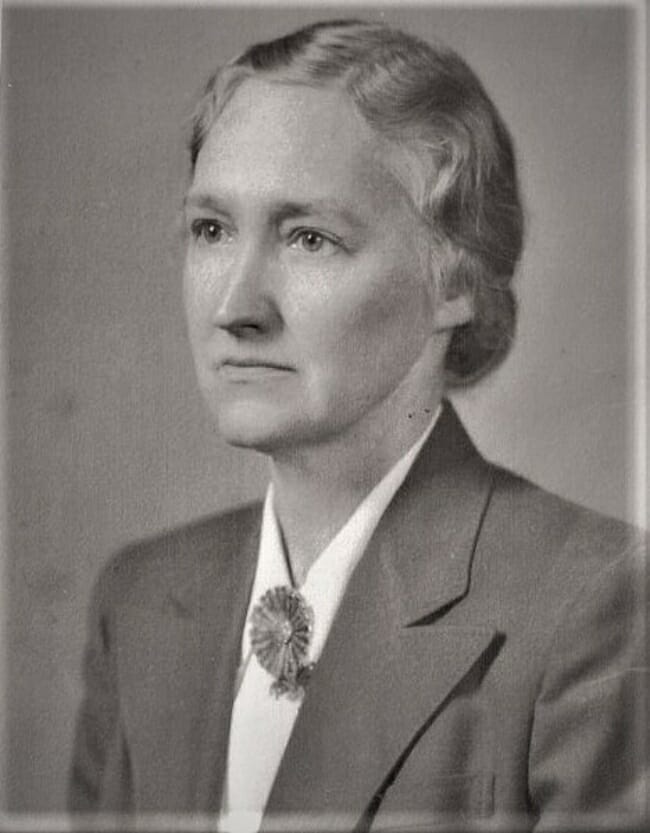

In the early 1900s, Dr. James Pittman was the only doctor in the town of Prairie Grove and the surrounding area. He often drove his buggy, pulled by his horse, Black Jo, through the winding roads of the Ozark foothills as he visited patients. Dr. Pittman wasn’t always alone on these trips. He had three children and often one of his two daughters would accompany him. The girls, Helen and Margaret, would administer vaccines and anesthesia to patients.

Although the practice would never be sanctioned today, accompanying their father on these trips rubbed off as both girls would grow up to pursue careers in medicine, along with their younger brother. Helen studied nursing and eventually chaired the nursing department at Sacred Heart Dominican College, while the youngest Pittman, named James after his father, became a surgeon and chief of the surgical staff at Herman Hospital in Texas. Margaret, however, chose a different path, which led to becoming a pioneering scientist.

Margaret Pittman was born on Jan. 20, 1901, two years after her sister. Her father died in 1919 after complications from surgery for appendicitis. The country doctor had time to leave his last request for his family. He instructed his wife to take the children to Conway where they could all attend Hendrix College. Margaret and Helen had already graduated from high school, but the family followed the doctor’s wishes. Margaret studied mathematics and biology. She was awarded the college’s Mathematics Medal. While Helen, Margaret and then James attended college, their mother, Virginia McCormick Pittman, sold canned vegetables and worked as a dressmaker to support their studies.

Margaret Pittman graduated magna cum laude in 1923 and taught for a year at the Girl’s Academy of Galloway College in Searcy. She then served as principal of the school for another year. Pittman then took the savings she had accumulated from her two years at the college and moved to Chicago, where she enrolled in the University of Chicago and studied bacteriology. After obtaining her master’s degree, she earned her Ph.D. in 1929.

After graduation, Pittman already had an offer at the Rockefeller Institute in New York. During her time there, she researched the bacteria Haemophilus influenzae, which continued the work she began as a doctoral student. While at the Rockefeller Institute, Pittman discovered how some of the strains of this bacteria are able to enter the bloodstream to cause a number of illnesses, including one form of meningitis most often found in children. Her research and following papers on the bacteria made her a renowned scientist by the time she was 30 years old.

Dr. Pittman joined the National Institute of Health (NIH) in 1936, where she would have a long career. In a 1988 interview with Dr. Victoria Harden, then Director of the Office of NIH History, Pittman said of her entry into the NIH: “I was much impressed by the number of studies that were directly applicable to public health. There was a great deal of collaboration.” Pittman started her research with Dr. Sara Branham, one of three women scientists at the NIH, and a former teacher from the University of Chicago. Together the women worked on the development of a potency assay for anti-meningococcal serum. “At the time, quantitative tests were not being done,” Pittman said in the interview, “But when we tried to get a standard value for antimeningococcus serum, we had no method to establish a minimum lethal dose. So I used the plain Reed-Münch method, which was a quick way of calculating, and so it was the first test that was introduced for the evaluation of the potency of products.”

When World War II erupted, work necessarily shifted toward researching why so many soldiers were having reactions after plasma and blood transfusions. Pittman describes the problem in her NIH interview. “Now the problem was that the plasma had to contain the plasma of not less than a thousand people in order to counteract the blood grouping substances.”

Pittman, along with colleague Thomas Probey, designed a process to scan the plasma for contaminants and tested how many contaminants could remain in a sample without causing reactions. “We found that there could not be more than 5,000 organisms per ml before the material was filtered. You see, they had been filtering and the organisms had been removed, but the pyrogen was still there.”

Pyrogens are substances produced by bacteria that can produce fever, and although the plasma was being filtered before it was administered to wounded soldiers, the fever-producing pyrogens were left behind. Pittman’s work helped thousands of soldiers who received both plasma and blood transfusions. Her work with blood samples also introduced a new technique where small vials containing a sample of the blood accompany the larger container so only the vial is tested for contaminants, avoiding the possibility of contamination that could occur by sampling the larger container.

An example of bags of blood with their sample vials, a process Dr. Pittman standardized.

By 1943, Pittman was moving from plasma to pertussis. Whooping cough was considered a childhood illness, infecting 200,000 children a year, with an average of 9,000 deaths. A vaccine existed, but it had more side effects than many vaccines, and some could be as severe as the disease. Pittman was asked to design a test for the potency of the vaccine, and to develop safety standards for its administration. In 1949, she set the standards for pertussis vaccinations in the United States, which the World Health Organization also adopted. Once pertussis vaccinations began in children, cases dropped swiftly. They reached an all-time low in 1976, with only 1,000 recorded cases in the U.S. that year.

Although the pertussis vaccination was a success, Pittman continued to work on it throughout her career, trying to pinpoint what caused the harsher side effects. In 1976, she realized pertussis contains an exotoxin, a toxic substance secreted by the bacteria into the surrounding cell. Her epiphany helped shift the vaccine to one with fewer side effects. “It is satisfying to have changed the direction of work on (the) pertussis vaccine,” Pittman said in 1988.

Pittman went on to be very involved with work on a cholera vaccine. She participated in lab work and research that involved the Cholera Research Lab in eastern Pakistan. She also became the first woman director of an NIH lab as Chief of the Laboratory of Bacterial Products in 1957. Pittman held this position until her retirement in 1971. She also contributed to work on both the typhoid vaccine and tetanus.

After retirement, she continued to work at the NIH as a volunteer, cutting her research and lab time down to 40 hours a week. She advised other researchers, presented lectures and workshops, and wrote many articles about her research. She also received numerous awards for her lifetime of service to public health, including the Federal Women’s Award in 1970.

In addition to her work, Pittman was an avid traveler. She frequently took the opportunity to explore the world after conferences or research that took her to other countries. She died August 19, 1995, and is buried in Prairie Grove, where her love for public health began so many years before as she traveled those winding country roads with her father.

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

One response to “Dr. Margaret Pittman – An Arkansas Pioneering Scientist”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

Wow! What a brilliant, fascinating woman. My mother and aunts who grew up in Searcy went to Galloway College.