Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

I believe that journalism is one of the world’s most noble professions. The very nature of our job is to pursue truth. Without facts, how can our democratic republic move forward as it should? Without truth, how can we possibly steer?” – Jerry Mitchell

In 1981, Jerry Mitchell graduated from Harding University with a degree in journalism. He took a job as an intern at the Texarkana Gazette, not knowing his career would one day reopen some of the most infamous cold cases in the South. Mitchell grew up in Texarkana in the 1960s and 70s, not immune to the turbulence of the Civil Rights Movement that gripped the nation. After his internship, Mitchell joined the Arkansas Democrat in 1982 before moving to the Hot Springs Sentinel-Record in 1983. It was with the Sentinel-Record that Mitchell cut his teeth on the type of investigative reporting that would eventually win him over 30 awards.

While in Hot Springs, Mitchell began investigating the Magic Springs theme park, “which was losing $1 million a year and which the city fathers had propped up with a $3 million bond issue,” Mitchell recalls. “The bond issue promised to spend much of the money on new rides for the park. Instead, most of it went to pay off loans that stockholders had made to the park.” Mitchell’s reporting brought to light the discrepancy, and a circuit judge threw out the bond issue as invalid.

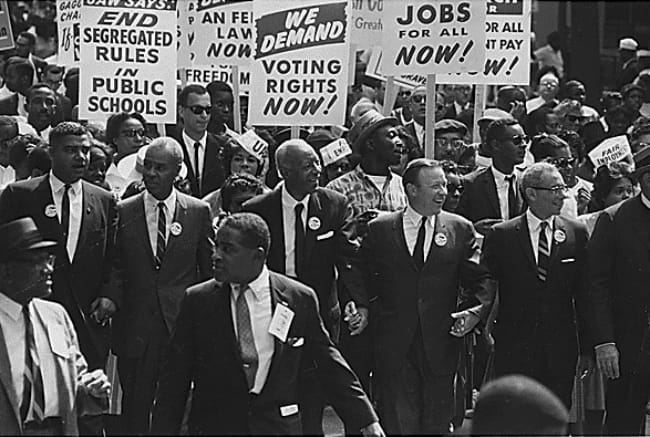

Mitchell left Hot Springs in 1986 for the Clarion-Ledger in Jackson, which would support Mitchell’s investigations for the next 33 years. Mitchell worked as a court reporter, but in January 1989, he found himself covering the release of “Mississippi Burning.” The movie examines the 1964 disappearance of three “Freedom Summer” campaign workers.

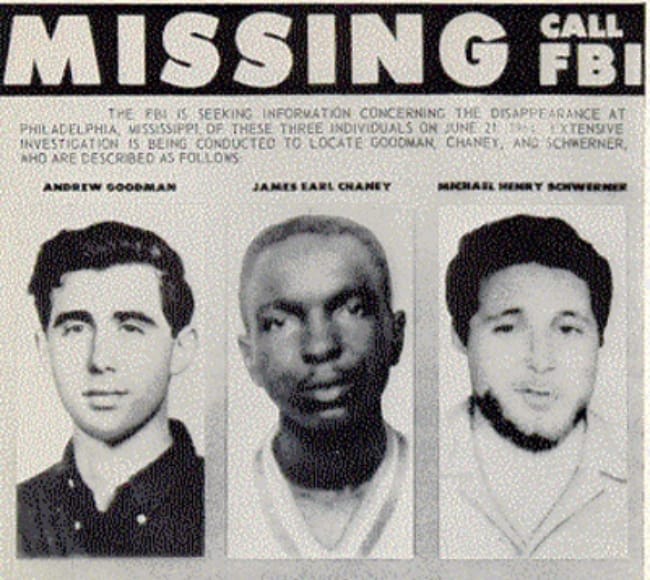

James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner traveled down to Mississippi as part of a voter registration movement. They were stopped in Neshoba County for speeding, held for questioning, and later released. The men then disappeared. An FBI investigation revealed the men were shot and buried below a dam. Though 19 suspects were indicted, only seven were convicted and received minor sentences. When Mitchell saw the movie, he walked away wondering how so many people could literally get away with murder. He began investigating the cold case.

The Mississippi Burning cold case led Mitchell to other cases in the South. He delved into the murder of civil rights activist Medgar Evers, a civil rights activist in Jackson, Mississippi. Evers was shot in his driveway by a long-range rifle. Byron De La Beckworth, a member of the White Citizens Council and Ku Klux Klan, was twice tried for the murder, but the all-white juries never reached a judgment. Mitchell’s legwork helped reopen the decades-old investigation. The new evidence he uncovered led to a new trial and a conviction in 1994.

Mitchell continued to pursue cold cases, setting his sights on the death of Vernon Dahmer. Dahmer was a civil rights activist in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. His house was set on fire on January 10, 1966. Amid shotgun fire, Dahmer helped his family escape the fire, but he died from severe burns and smoke inhalation. Fourteen men, many of them Ku Klux Klan, were originally indicted for murder and arson, but only four were convicted, with three walking away with pardons after a few years. Sam Bowers, the Ku Klux Klan leader, had been tried four times with no convictions. After Mitchell’s investigation prompted the state of Mississippi to reopen the case, he was convicted of Dahmer’s murder in 1998.

Perhaps the most famous cold case Mitchell picked up was the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. The church had become a central point for civil rights in the city. Martin Luther King, Jr. and other activists met there, and in May of 1963, children gathered to train for the 1963 Children’s Crusade, a series of marches that led to the desegregation of Birmingham schools. That September, only two weeks after the first three schools desegregated, four known Klansmen planted a bomb beneath the steps of the church.

When the bomb detonated, it killed four girls ages 11-14 and injured 22 others. Though the FBI was able to trace the bomb to the four Klansmen, the trial was not held until 1977, when one of the men, Robert Chambliss, was convicted of the murder of one of the girls, eleven-year-old Carol Denise McNair. In 1995, after Mitchell’s investigative work into the case, the case was reopened and two other men, Bobby Cherry and Thomas Blanton, Jr., were brought to trial and eventually convicted. The fourth man, Herman Cash, had already died.

In “Race Against Time,” Mitchell details how he walked through each case, often seeking out family members and friends of those who died, to piece together the events and gather evidence. The book is so titled because Mitchell felt the constraints of time on each investigation as the perpetrators grew older, as did witnesses and family members. The book is a recommended read by Oprah Magazine and novelist John Grisham “called the true-crime book an ‘amazing story’ and one of the best books he’s read in recent years.”

When Jerry Mitchell first began his newspaper career in Arkansas, he couldn’t have imagined his role in bringing criminals to justice. Still, he states, “there’s no question that my time as a young reporter in Arkansas paved the way for my investigative reporting in Mississippi and across the South. This introduction to investigative reporting proved key to the later investigative reporting I would do in Mississippi surrounding some of the most notorious murders in U.S. history, where in case after case, those murderers had walked free.”

In 2019, Mitchell left the Clarion-Ledger to found the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, a non-profit focused on training a new generation in the vital role reporting plays in the pursuit of justice. Mitchell says, “With newsrooms shrinking and vanishing, MCIR is providing the investigative and in-depth reporting that the state desperately needs. We mainly focus on Mississippi, but we’re doing some reporting across the South as well. For instance, we’re chasing the Tiger King case now. Without truth, there can be no justice.”

With the center, Mitchell stays true to his calling to seek out injustice and flip the scales. “Race Against Time” is the story of the pursuit of justice decades later.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Kimberly Mitchell

Scott Fitzgerald never forgot the feeling of freedom he got from biking...

Trains revolutionized the United States in the 1800s. People and goods...

The American Black Walnut is a unique nut for many reasons, and Arkansas...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment