Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

If there is one sound I listen to as summer deepens, it’s the chainsaw song of cicadas as they sing from treetop perches. Their loud buzzing is ingrained in my summer memories, and perhaps yours as well. This year those buzzes might sound a little louder as a new brood of periodical cicadas emerges in Arkansas. While it’s not an event you likely had on your summer calendar, scientists track these periodical broods with precision and 2024 is a special year. This year, two different periodical broods emerge simultaneously, ensuring the eastern half of the United States will be abuzz with the songs of cicadas.

Cicadas Are Unique. They’re Neither Grasshoppers Nor Locusts.

Often mistaken for locusts, cicadas are a species of their own, or more accurately, many species. Cicadas form a group called Cicadoidea and there are 3,000 known species, but likely many more are still unknown. They exist all over the world, including Arkansas. The word cicada is pronounced si-kah-duh or si-kay-duh. While both are correct, you’re more likely to hear the second in Arkansas. Arkansas is home to at least 24 different species of cicadas. Many of these are annual cicadas. They appear every year in late spring and early summer and have such entertaining names as Fall Southeastern Dusk-singing Cicada, Dog-day Cicada, Scissor-Grinder and Swamp Cicada. These names are not the scientific designations for these species, but the more descriptive versions of each type of cicada and when or where they can be found.

Cicadas are born in trees or near them. A single female can lay up to 400 eggs and prefers twigs and branches as a laying site. After six to ten weeks, tiny white nymphs hatch from the eggs and burrow into the ground, where they’ll spend most of their life cycle. Beneath the ground, cicadas drink from tree roots and grow, usually molting several times. After a period of time, which can range from one to 17 years underground, depending on the species, the cicada tunnels to the surface. Once above ground, it scurries to a nearby tree, house, barn or any vertical wood structure to climb to a safe spot and molt one final time. As the cicada sheds its outer layer, it leaves behind its nymphal skin, which will dry into a hard brown shell. Have you happened upon these shells clinging to your house or tree? A cicada emerged there.

What’s All The Noise About?

As soon as cicadas shed their skin, they change color from pale white to brown, black or even green and expand their wings. Now they’ve reached the final, and busiest, stage of their lives. They quickly fly to trees and begin to mate, which involves that loud sound they’re most known for. Male cicadas have tymbals, membranes that stretch over part of their abdominal region. The males vibrate these tymbals to produce that signature high buzz. Some species also beat their wings together to create other sounds. The buzz draws females to the male to mate. The volume of sound can also ward off predators. After mating, females find a suitable branch or twig and lay their eggs. Both males and females die soon after mating, making their adult life aboveground the shortest part of their life cycle.

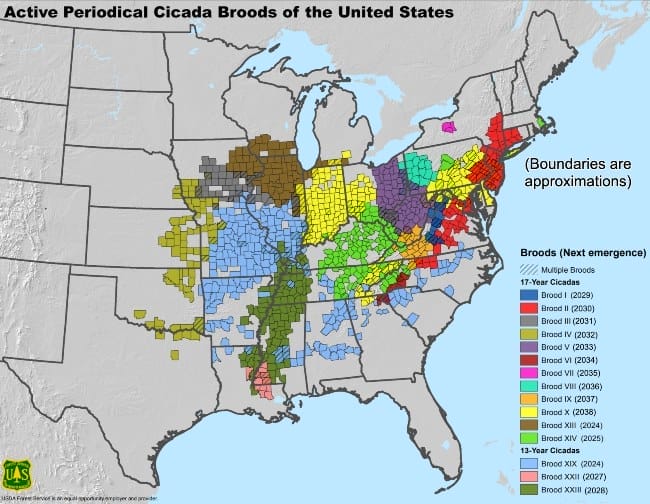

While annual cicadas add their pleasant buzz each summer, there are a few species of cicadas that can change that buzz into an ear-splitting screech that can damage human hearing. These are the infamous brood cicadas that emerge in periodic cycles of 13 or 17 years. These periodical cicadas, known as Magicicadas, are unique to the eastern United States. There are 15 broods of periodical cicadas, with 12 of these broods emerging on 17-year cycles, though not all in the same year. Three broods emerge in 13-year cycles. The broods are designated by Roman numerals, and Arkansas is home to two of these periodical broods. Brood XIX, the Great Southern Brood, has been recorded since 1803 and every 13 years emerges in large numbers, sometimes up to 1.5 million cicadas per acre.

Although that is a stunning number, they don’t have equal distribution across the South. In Arkansas, this brood prefers the White River drainage area in Northwest Arkansas. They have also been spotted in Northeast Arkansas. Brood XIX is the periodic brood emerging this year, and part of the reason some news stories have claimed a sort of cicada-geddon this summer. Another periodic brood on a 17-year cycle is also emerging this year, Brood XIII. It is rare for the emergence of two periodical cicadas to align like this. Although these broods emerge reliably on their respective 13- and 17-year cycles, it takes 221 years for these cycles to coincide, and this is the year.

Map of Periodic Cicada Broods in the United States. The light blue in Arkansas is Brood XIX, already emerging this year. The dark green is Brood XXIII and will emerge in 2028. Map by Andrew M. Liebhold, Michael J. Bohne, and Rebecca L. Lilja via Wikimedia Commons.

Does that mean we’ll see an unusual number of cicadas this summer in Arkansas? Yes and no. The emergence of Brood XIX will certainly add numbers to the cicada population in Arkansas, but the territories of Brood XIX and XIII don’t overlap. While we’ll see Brood XIX in Arkansas, you’ll have to head north to Illinois to find Brood XIII. While it’s possible there may be a little overlap between the two broods in Illinois, it won’t happen this far south. However, with the addition of Brood XIX in Arkansas this year, it will be noisier in wooded areas where the brood emerges.

How To Identify That Cicada on Your Tree

All cicadas crawl out of the ground into trees, leave their exoskeletons behind, and become adults with wings. Each species is slightly different though. Annual cicadas are typically green, brown and black. These colors vary with the species. Scissor grinder cicadas are mostly green while prairie cicadas are mostly brown. Annual cicadas also have brown or black eyes and wings that are black or tinged with green. Periodical cicadas are quickly identifiable by red eyes, black bodies, and orange wing veins. Every species of cicada also has a unique song. Brood XIX cicadas sing during the day, so if you’re out during a warm June day and hear that buzzing song, it’s a periodical cicada. Annual cicadas prefer to sing at sunset. These different times and songs attract only the females from their respective species to breed. Some cicadas emerge later in the summer than periodical cicadas, like dog-day cicadas, who emerge in July and August, so when you hear the buzz saw songs in late summer, you can be sure these are annual cicadas.

Brood XIX isn’t the only periodical brood in Arkansas. Brood XXIII, or the Lower Mississippi River Valley Brood, is another 13 year brood that emerged in 2015 and will reappear in 2028 across Northeastern Arkansas, particularly the Crowley’s Ridge area. Don’t look for another brood to emerge with this one, though. The next time two periodical broods emerge in the same year will be in 2245. That makes 2024 extra special.

Brood XIX cicada in 2011 by Philip N. Cohen in Wikipedia.

Are Cicadas Dangerous?

Although periodical cicadas can be loud, they are not dangerous. Cicadas also do not damage gardens, bite or sting. They can damage young trees, though, as they rely on sap from trees to sustain them for the four to six weeks of their lives above ground. They have many natural predators, including copperhead snakes, fish, box turtles, spiders, dragonflies, birds and moles. Cicadas have a few unnatural predators as well. Dogs will eat cicadas, and cats are known to play with them, of course, before consuming them. A few cicadas probably won’t harm your pet, but don’t let them eat too many. They may have trouble digesting the hard exoskeleton.

People are also known to eat cicadas, especially when periodical cicadas emerge and overwhelm an area. If you’re interested in trying it, they’re best when harvested immediately after molting, or shedding their hard exoskeleton, but before their new shells have fully hardened. Search around the base of trees in the early morning hours for a white cicada. These cicadas are waiting for their shells to harden. Put them in a bag and freeze your harvest to humanely kill them before cooking. There are recipes for cicadas if you’re brave enough to try it. You can find anything from spicy popcorn cicada to stir fry to cookies. People report they have a nutty taste and provide excellent protein with few calories. However, if you have a shellfish allergy, stay away from them. Cicadas are related to lobsters and other shellfish.

This summer, whether you’re out in the woods or simply listening from your porch, you’re likely to hear the call of cicadas. Whether you love or hate the buzzing song, it’s all part of summer in Arkansas.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Kimberly Mitchell

The XXV Winter Olympics concluded this February in Italy, and one of the...

Scott Fitzgerald never forgot the feeling of freedom he got from biking...

Trains revolutionized the United States in the 1800s. People and goods...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment