Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

Arkansas is known for its farmland and many of its crops. Rice, wheat, corn, cotton and soybeans are grown across the state. However, the state also has its own berry which can be traced to a small community that made a name for itself and its unique berry over 80 years ago – the lavacaberry.

Lavaca is in Sebastian County near the Arkansas River. Originally, it served as a stop for soldiers arriving from Little Rock in the state’s territorial days when Fort Smith was just established. For decades its population hovered between three and four hundred people before experiencing a small population boom in the 1980s to propel its numbers past 1,000. Currently, the community is part of the Fort Smith metropolitan area with a population of 2,450.

How did this small community become associated with a distinctive berry? For years, the city of Lavaca served the mostly rural community, where farmers grew more typical crops and raised cattle. The town had two cotton gins, grocery stores and eventually a movie theater. The community even did well during the Depression, but at the end of the Depression, as war loomed on the horizon, it experienced a downturn. The crops and jobs that had sustained it dwindled and farmers quickly began searching for an idea to diversify their revenue. It came from a surprising source.

Local school instructor Idus Fielder recalled a unique berry he’d seen at a farm in White County. The farmer had purchased red raspberry plants from Burbank, California in 1927. Lavaca farmer Ed Girard made the trip to White County and bought 1,000 of these California red raspberry plants for his own farm. He planted 1 acre in 1938, had a very successful crop, and sold the berries for $1.50 a crate, with between 100 and 200 crates of berries. News of Girard’s cash crop spread to other local Lavaca farmers, who followed in Girard’s footsteps with their own plantings. Girard expanded his crop from that initial acre to over 300 acres of berries.

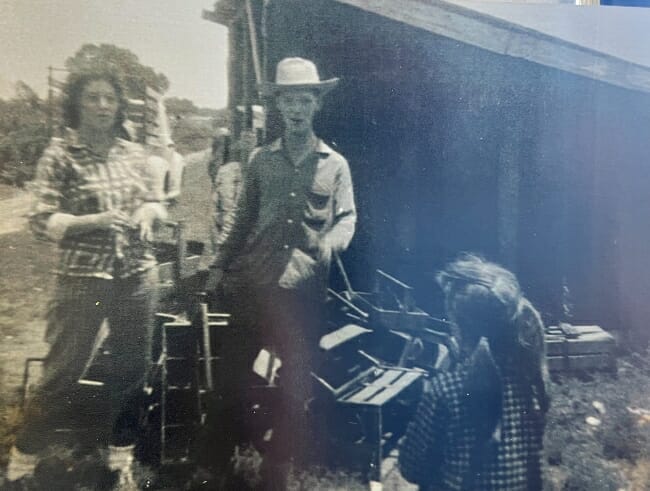

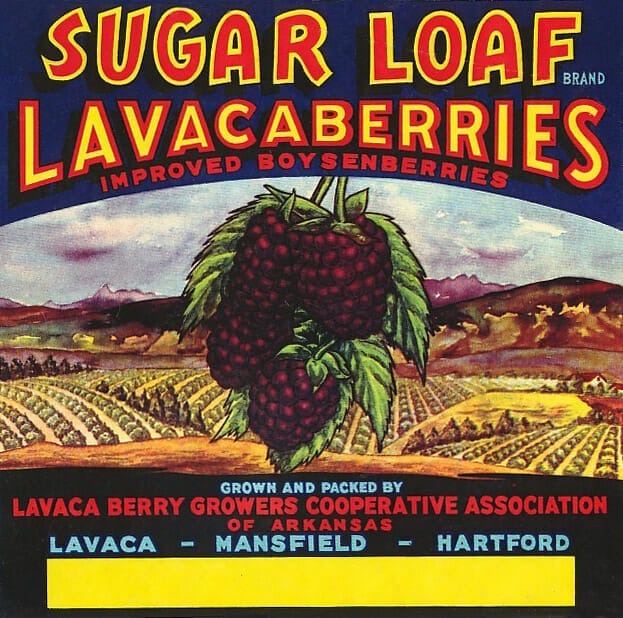

With the growing crop and profits, Lavaca built its own berry shed instead of relying on a produce company in Van Buren. Farmers could bring their berries to the shed, have them weighed, and get paid right away. Lavaca went from a struggling, dying community to a successful one in a few short years. The farmers formed the Lavaca Berry Growers Association in 1946 to help them negotiate a higher but stable price. In one day in 1943, the berry shed weighed over 600,000 pounds of berries, numbering well over 15,000 crates. These berries received a label proclaiming the Sugar Loaf brand, but they were sold from Lavaca’s association, which included growers in Mansfield and Hartford. The berries were shipped across the country and marketed as “improved boysenberries.”

The berries caught the attention of national growers and caused a bit of controversy over what the berry was, exactly, and how it should be priced. It looked like a blackberry but tasted more like a raspberry. In 1944, an effort began to establish what the lavacaberry was. In 1948, the U.S. Department of Agriculture decided the berry was most closely related to a boysenberry. Boysenberries are a cross between raspberries, blackberries and loganberries and were developed in California during the Great Depression. However, the lavacaberry is not a boysenberry. Some speculate it’s a cross between the original California raspberry brought to Arkansas and wild Arkansas blackberries. Whatever the fruit’s origin, the Lavaca Growers Association decided to keep the name lavacaberries.

Unfortunately for local growers, large fruit producers from outside the state began to import berries into local stores and sell them at cheaper prices. Slowly the lavacaberries became less profitable. In 1959, the local growers stopped using the berry shed. While some continued growing the berries, they were more for backyard gardens than shipping. In the 1970s, the Lavaca Berry Growers Association met one last time to sell the property the berry shed was on and disband. Eventually, many of the berry fields were plowed with other crops, or the land was sold and turned into subdivisions and businesses.

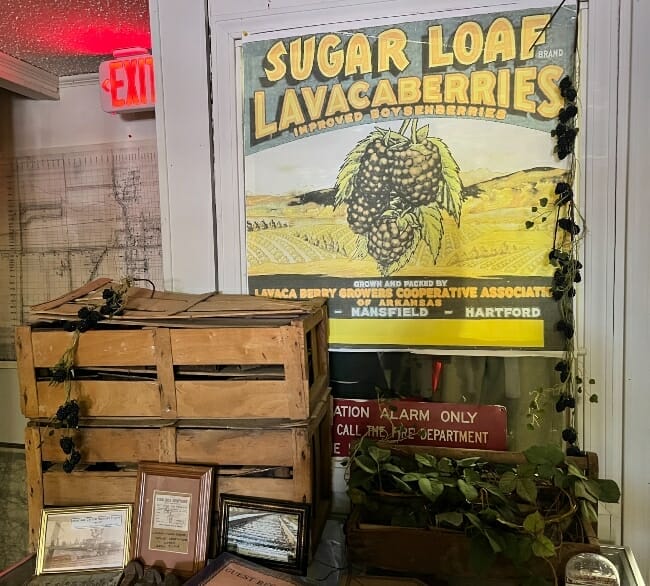

However, Lavaca wanted to hold on to its unique berry image. The Lavaca Berry Festival held in late spring celebrates the town’s connection to this unusual berry and features homemade jams and jellies, crafts, vendors, live music and more. Lavaca’s town history, including the lavacaberry, is on display at the Military Road Museum of Lavaca in downtown Lavaca. To find out more about the Lavaca Berry Festival, follow the Facebook page. If you’re in Sebastian County, or you know someone who lives there, you might just ask if they have lavacaberries growing in their backyard and get the chance to taste this Arkansas berry for yourself.

All photos are courtesy of the Military Road Museum.

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

One response to “The Lavacaberry: Arkansas’s Original Berry”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

Hi, thank you for this great story. It is a great piece of history that could easily be forgotten. These berries sound amazing and I hope someone is still growing them. Does anyone know if you can still buy Lacaberries or the plants?

Thank you!