Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

In 1942, the Americans Tom Brokaw would later celebrate as our country’s “Greatest Generation” had survived World War I, the Great Depression, and a series of floods and droughts that created unprecedented hardships. The historic hard times failed to break their will, but just as life seemed to be getting easier, the previous year had ended with the foreboding reality of a second World War.

I honestly feel that it would be best for the country to keep baseball going.” –President Franklin Roosevelt, Jan. 1942

Recreation, entertainment, and sports were secondary to the complete dedication necessary for national defense. Pro baseball faced a difficult decision. Was there a place for ball games where every available individual was part of the workforce, and there was little disposable income for outings at the ballpark?

Even the all-powerful Commissioner of Baseball, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, declined to make the call to “play ball” in 1942. The decision on the future of “America’s Pastime” would be determined through an arduous process that finally landed on the desk of the President of the United States, Franklin Roosevelt.

In what would become known as the “Green Light Decision,” President Roosevelt’s letter to the Commissioner on January 15, 1942, urged baseball to continue during World War II. FDR, a baseball fan, believed that the game provided “essential, short, inexpensive recreation for citizens and helped take their minds off war work.”

The decision that minor league baseball could continue in 1942 was not big news in Little Rock. The Travelers had not had a winning season since the 1937 Southern Association Championship team. The 1941 team was last in the league in attendance, averaging about 500 paying customers in a league known for large minor league crowds. In describing an apathetic fanbase in towns like Little Rock, sportswriters often described home crowds where fans “stayed home in droves.”

After the unexpected title in 1937, the Little Rock Travelers had returned to their accustomed position near the bottom of the standings. In the “Catch-22” of minor league baseball, losing teams led to low attendance, inadequate budgets, and an inability to attract quality players. At times, only the shrewd leadership of general manager Ray Winder kept the Little Rock franchise afloat. In the darkest days of wartime baseball, the Travelers’ luck was about to change.

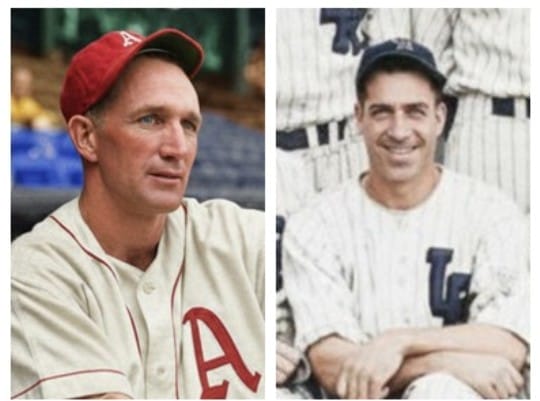

A major league pitcher from Oklahoma named Willis Hudlin was looking for a home in minor league baseball. Hudlin had been the ace of the Cleveland Indians’ pitching staff for ten seasons after arriving as a 20-year-old in 1926. The big farm boy with a blazing fastball won 125 games before his 30th birthday, but arm problems left him searching for a minor league town near his home in Oklahoma. Little Rock, Arkansas, would be a good choice, and to assure his job security, he could buy a share of the team.

Hudlin won 14 games in 1941, his first year as a Traveler, but the team finished sixth in an eight-team league. In a bold budget-saving move to build a better team quickly, Hudlin, the owner, hired Hudlin, the pitcher, as manager in 1942. The player-manager won 11 games on the mound and led the team in ERA. Hudlin also leveraged his connections in pro baseball to locate overlooked players Little Rock could afford.

Finding Pitchers

Hudlin knew he would need to limit his personal pitching work to devote more time to managing the team and protecting an overused pitching arm. He found the most surprising answer to the pitching question in a little lefty who had been released at Buffalo in the International League.

Frank James “Jim” Trexler was a major league prospect on the way up until two unimpressive years at minor league baseball made him available to a Southern Association team trying to rebuild. Trexler won a team-leading 19 games as the ace of the Travelers’ staff.

Like Trexler, Albert Thomas “Hiker” Moran was once a potential major leaguer. Moran had pitched in seven games with the Boston Red Sox in the late 1930s before three lackluster years in the high minors made him affordable in Little Rock. Moran won 17 and lost 9 for the pennant-winning Travs and led the team in innings pitched.

Along with the veterans on the way down, Hudlin found 24-year-old Eddie Lopat in mid-season, stuck in the minors due to his reputation as a pitcher without a fastball. Lopat finished the year strong, winning some of the Travs’ most important games down the stretch.

Hudlin’s Misfits Become a Championship Team

When Willis Hudlin began assembling his new roster from players released from other minor league teams, a local sportswriter labeled them “Hudlin’s Misfits.” One of his first recruits was his old friend Buck Fausett.

Robert “Buck” Fausett was officially retired after batting .228 as a part-time infielder in Minneapolis in the American Association when he jumped at one more chance to prove himself. The offer to play in Little Rock would bring Fausett back to his home state and restore his big-league dream.

Born in Grant County, Arkansas, a crowd favorite the press called “Leaky” Fausett, thrived in Little Rock playing before family and childhood friends. The 34-year-old minor league veteran led the team in batting average (.334) and hits (188).

Fortunately, Hudlin found his cleanup hitter, Jim Tyack and the league’s MVP, Roy Schalk, on the roster he inherited. James Fredrick Tyack, a three-sport legend in Bakersfield, California, had reached the highly competitive Pacific Coast League before a series of injuries found him trying to revive his career in Little Rock. In 1942, he recovered to become a middle-of-the-lineup power guy, leading the Travelers in home runs and three-base hits. Schalk, the veteran leader of the club, drove in 88 runs and led the team in double plays.

Hudlin’s misfits were in first place most of the season, but Nashville was a close second until Lopat arrived to supplement a short-handed pitching staff. A 13-game winning streak late in the season gave the Travs some breathing room.

As President Roosevelt had predicted, almost 100,000 war-weary fans had found the time and money to attend a baseball game at Travelers Field. While the early war news was discouraging, a parade through the city gave fans something to cheer about. The Southern Association Champions proved that America’s Pastime had a place in the war effort.

After the Magic

In 1943, Hudlin handed off the managerial duties to Buck Fausett. The Travelers finished in third place, six games behind league leader Nashville. The Travs dropped to fourth in 1944 and did not reach the first division again until the “Miracle Season” of 1951. Fausett enjoyed five more successful years as a minor leaguer and 13 games with the Reds in the National League.

After winning the Southern Association title, Jim Trexler, pitching ace of the 1942 Travs, would never get the expected big-league call and ex-major leaguer. Hiker Moran, who had briefly pitched in the major leagues, would not earn a second chance.

Hitting star Jim Tyack’s 1942 season in Little Rock earned him only a brief shot with the 1943 Philadelphia Phillies. The Jim Tyack Award is presented annually to outstanding high school athletes in Kern County, California. MVP Roy Schalk would finally earn two seasons as the second baseman for the Chicago White Sox.

Eddie Lopat, who was instrumental in the stretch run to the 1942 pennant, won 50 games in four years with the Chicago White Sox before being traded to the Yankees, where he was part of five World Series Championships.

Willis Hudlin remained in Little Rock for the remainder of his life, working at various baseball-related jobs. He was inducted into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame in 1977.

Cover photo: Front row left to right – Rosie Cantrell, Wes Westrum, James Oglesby, Buck Fausett, Willis Hudlin, Leroy Schalk, Herb Bremer and Fred Hancock. Back row left to right – William Shirley, Joe Callahan, Frank Papish, Tom McBride, Charles Hawley, Hiker Moran, Jim Tyack and John Intlekofer.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Jim Yeager

In 1920, the winter days between Christmas and New Year’s Day promised...

The 1951 baseball season arrived in Little Rock with little cause for...

In 1994, Hall of Famer Ted Williams was contracted to create his personal...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment