Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

Our fridge has an ice maker, but it often “goes on vacation,” as we like to say. It will work fine for weeks until suddenly the cubed ice button produces crushed ice instead, a sure sign that the ice maker is about to take a few days off from production. There is no rhyme or reason to it, and it’s super frustrating because I drink a lot of water and like it with a lot of ice. Recently, it got me thinking about a time before refrigeration, when ice was scarce and had to be harvested in winter and stored for long-term use.

Public Domain

In the 21st century, our most common use of block ice is to cool drinks or perhaps keep that recently harvested deer fresh. Although evidence of adding ice to drinks dates back to antiquity, iced drinks were reserved for royalty and the extremely wealthy until the 19th century. The main use of ice was for food preservation, and by the mid-1800s, ice harvesting had become common even in Southern states like Arkansas.

By 1865, ice houses had sprung up across the South, giving locals regular access to stored ice harvested in winter. Every cold spell was taken advantage of, and men waited for local lakes and ponds to freeze thick enough that they could cut the ice into blocks using long hand saws. The blocks, often weighing hundreds of pounds, were packed tightly in icehouses, buildings sometimes built partly underground that were insulated with layers of straw and sawdust to slow down melting.

Public Domain

Arkansas’s mild climate meant deep freezes were not guaranteed every winter, but when a good freeze came, communities made the most of it. Some towns imported ice when necessary, shipping frozen blocks by railroad or riverboat from colder regions. However, locally harvested “native ice” was cheaper and a source of local pride.

Hot Springs, Fort Smith, Little Rock and other towns had icehouses in the late 1800s, ensuring that even in July one could buy a chunk of last winter’s ice. These icehouses were often located near waterways or railroad depots, making it easier to gather ice or receive shipments.

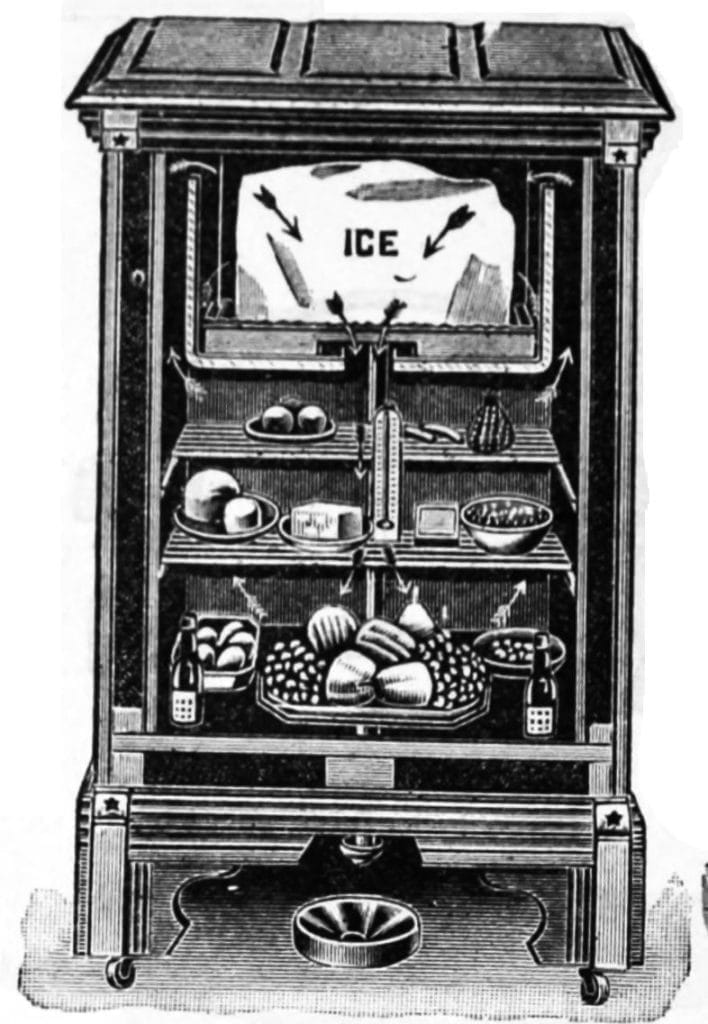

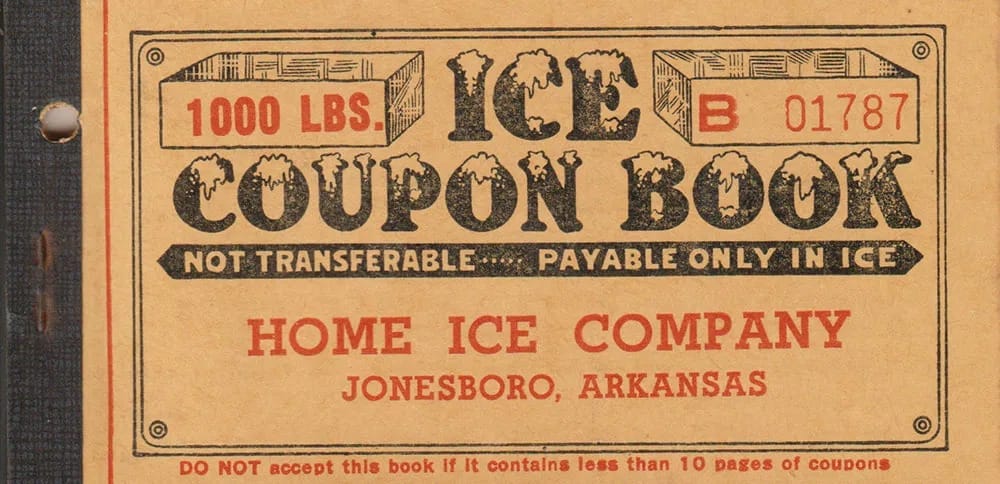

Before modern refrigerators, families stored food in insulated iceboxes, wooden cabinets lined with metal. Every few days, an iceman would deliver a fresh block of ice to place inside the top compartment of the icebox and as it slowly melted, it would chill the food below. Initially, the ice came from the local icehouses, but as technology improved and mechanical refrigeration became more common, icehouses were out and local ice factories became more common. By the early 1900s, most towns in Arkansas had ice plants or ice depots that sold blocks of ice to residents. Horse-drawn wagons, and later, Model T trucks, made the rounds with dripping blocks of ice covered in burlap. Children would scramble to grab slivers of fallen ice as treats, and having a daily ice delivery was just a normal part of life.

Even with ice deliveries available, rural Arkansans often had to be resourceful, especially those far from town icehouses. Farm families commonly preserved food in cellars or springhouses. A springhouse was a small structure built over a cold spring or creek, where crocks of milk and butter could be set in cool, flowing water. Likewise, root cellars dug into hillsides provided a cool, humid environment to keep vegetables crisp. But one of the most fascinating methods was the use of natural caves. In Cave City, for example, the Crystal River Cave stays around 57°F year-round. While touring the cave, the owners mentioned that it once served as a communal refrigerator. Families would venture down into the dim caverns with their perishable goods like meat, milk and eggs to store them in the cool darkness. The cave’s natural coolness safeguarded food from spoiling in the blazing summer heat, long before electricity or appliances were available in the area.

The practice of harvesting ice, insulating icehouses, building springhouses and cellars, and even cooling food in caves highlights how challenging daily life could be before modern refrigeration. Nowadays, we can buy twenty-pound bags of ice from a vending machine at the corner gas station or simply press a button on our fridge. In the past, keeping food fresh was a constant battle against heat and time.

Looking back, it’s difficult to imagine how much effort was once spent just to keep food cold. Keeping our food chilled hasn’t always been as easy as pressing a button, and the history of ice harvesting in Arkansas is certainly a fascinating reminder of life before the age of refrigeration.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Julie Kohl

I was a little late to the podcast party. I wanted to love them, but...

Hiking in the winter can be a surprisingly fun and magical experience. We...

The minute snow starts falling, I’m usually the first one bundled up...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment