Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

This Black History Month, we pay tribute to the innumerable African-American men and women who have blazed trails and left an indelible mark on American history, because black history is American history. We’re featuring just a few of the firsts by some incredible Arkansans. You can find more firsts by visiting the online home of the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame and The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture, a project of the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies at the Central Arkansas Library System (CALS) in Little Rock, Arkansas.*

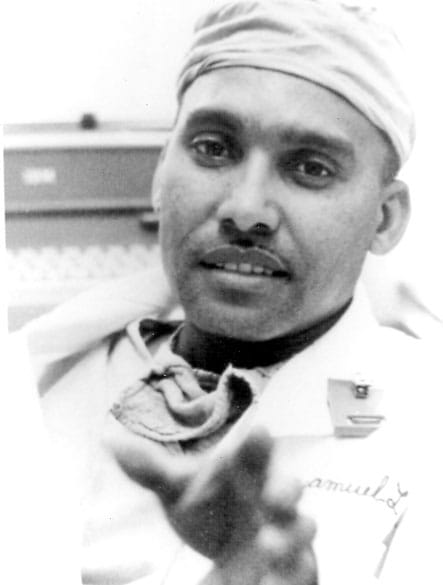

Dr. Samuel Kountz. Photo courtesy: University of California at San Francisco, The Library, Special Collections

Dr. Samuel Kountz: Pioneer in organ transplantation

The medical profession will be forever enhanced by the contributions of the Dr. Samuel Lee Kountz. The Lexa native and AM&N (now University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff) graduate performed the first kidney transplant between a recipient and a donor who were not identical twins. This single achievement guaranteed his status as a pioneer in surgery. During his lifetime, Dr. Kountz performed more than 500 kidney transplants. In 1965, he performed the first renal transplant in Egypt as a visiting Fulbright professor in the United Arab Republic. While director of the transplant service at the University of California at San Francisco, Kountz made the breakthrough observation that high doses of a certain steroid hormone arrested the rejection of transplanted kidneys. This discovery led directly to the current drug regimens that make organ transplants using donations from unrelated donors routine.

Florence Price. Photo courtesy: G. Nelidoff, in Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville

Florence Beatrice Price: Acclaimed composer

Florence Beatrice Price, of Little Rock, is the first African-American female composer to have a symphonic composition performed by a major American symphony orchestra. Smith received her formal education in piano and organ at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts, which was a notable achievement for a black woman in 1907. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra performed her Symphony in E Minor on June 15, 1933, under the direction of Frederick Stock. The work was later performed at the Chicago World’s Fair as part of the Century of Progress Exhibition. The orchestras of Detroit, Michigan; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and Brooklyn, New York, also performed symphonic works by Price. Renowned contralto Marian Anderson featured Price’s spiritual arrangement “My Soul’s Been Anchored in de Lord” in her famous performance on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. on Easter Sunday, April 9, 1939. In her lifetime, Price composed more than 300 works, ranging from small teaching pieces for the piano to large-scale compositions such as symphonies and concertos, as well as instrumental chamber music, vocal compositions, and music for radio.

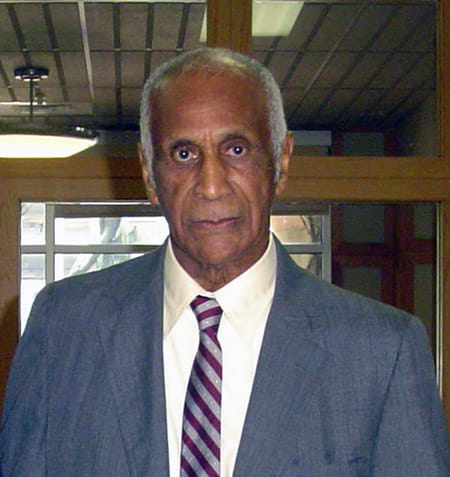

Vertie Carter. Photo courtesy: Arkansas Black Hall of Fame

Vertie L. Carter, EdD: Distinguished educator and equal pay advocate

Born into a sharecropping family in 1923, Vertie L. Carter grew up in a two-room shack on a plantation in the Antioch community in Hempstead County. After earning a bachelor’s degree from AM&N College, she attended classes in Little Rock to earn a master’s in education from the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, because Blacks were not permitted on the Fayetteville campus. She received her doctoral degree from the University of North Texas in Denton. While working at Philander Smith College in Little Rock she established a Teacher Education Laboratory with personal funds and led the college to receive its accreditations. Dr. Carter was appointed by three governors to serve on the Arkansas Merit System Council to monitor equal employment opportunity (EEO) in state jobs; she was the first African American, first woman, and first educator to serve on the council and chaired the council for seven years. During this time, she wrote a book called How to Get a Career Job and held seminars to help people apply for and test for state jobs. After pointing out that there were no black members of the Oral Review Board, she selected two to serve on the board. Dr. Carter also served as second vice president of the International Personnel Management Association and vice president of the advisory committee on affirmative action.

Faye Clarke. Photo courtesy: Arkansas Black Hall of Fame

Faye Clarke: Prominent Businesswoman

Pine Bluff native Faye Clarke was the first African-American woman to graduate from Harvard Business School. She went on to serve as regional vice-president at food giant ARAMARK. When Mrs. Clarke retired in 1991, she and her husband, Frank, used $250,000 from their retirement fund to purchase school supplies for poverty-stricken students and founded the Alabama-Mississippi Education Improvement Project, Inc. The organization is now known as Educate the Children Foundation. Today Educate the Children Foundation of Huntington Beach, Calif., is a clearinghouse and distribution center for more than $20 million in books, supplies and equipment that go to eligible schools throughout the United States. Faye Clarke serves as executive director. Along with her husband, she has received numerous awards and honors including the 1996 President’s Service Award, awarded at the White House by President Bill Clinton.

Milton Crenchaw. Photo courtesy: Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Central Arkansas Library System

Milton P. Crenchaw: Outstanding Airman

Milton Pitts Crenchaw, of the original Tuskegee Airmen, was one of the first African-Americans in the country and the first from Arkansas to be trained by the federal government as a civilian licensed pilot at a time when Jim Crow laws were still in effect. He trained hundreds of cadet pilots while at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute in the 1940s and was the catalyst for the first successful flight program at Philander Smith College in Little Rock. For more than forty years from 1941 to 1983, Crenchaw served with the U.S. Army (in the Army Air Corps) and eventually the U.S. Air Force. He was inducted into the Arkansas Aviation Hall of Fame in 1998. In 2007, President George W. Bush awarded Crenchaw and other members of the Tuskegee Airmen the Congressional Gold Medal. The Tuskegee Airmen are the largest group to ever receive this medal. Crenchaw was also inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame.

Judge Mifflin Gibbs. Photo courtesy: Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Central Arkansas Library System

Judge Mifflin W. Gibbs: Prominent businessman and politician

Mifflin Wistar Gibbs was a Little Rock, Arkansas businessman, politician, and the first elected African-American municipal judge in the United States. Gibbs, born on April 17, 1823, became a successful retail merchant and a leader of the growing black population in San Francisco, California, before settling in Little Rock, Arkansas. He was a founder of the first black newspaper west of the Mississippi River, The Mirror of the Times in 1855. In November 1874, Gibbs won election as Little Rock Police Judge in a tight race and served until April 1875, when the Democrats defeated him at the end of Reconstruction. However, Gibbs continued to wield power in the Republican Party, serving for a decade as secretary of the state GOP central committee. He was often a delegate to national conventions, and in 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes named Gibbs registrar of the Little Rock district land office; President Benjamin Harrison named him receiver of public monies in Little Rock in 1889. Finally, President William McKinley named him U.S. consul to Madagascar in 1897. A Little Rock School District elementary school is named in his honor.

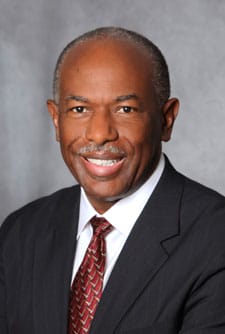

James Hildreth. Photo courtesy: Arkansas Black Hall of Fame

James E. K. Hildreth: Brilliant Physician and researcher

As a leading HIV/AIDS researcher, James E. K. Hildreth, M.D. is dean of University of California–Davis College of Biological Sciences. Dr. Hildreth was born and raised in Camden and went on to become the first African American Rhodes scholar from Arkansas. Dr. Hildreth graduated magna cum laude from Harvard with a degree in chemistry. He then went to Oxford University in England as a Rhodes scholar where he earned his doctorate in immunology. Hildreth returned to the United States to attend Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, where he earned a medical degree in 1987. Dr. Hildreth used a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to partner with black churches in thirteen states to educate people about HIV. He also traveled to Zambia in 2006 to test his HIV-killing cream, which he began to research in 1986 with the goal of helping developing countries lower their HIV infection rates. For the same reason, he later traveled to South Africa.

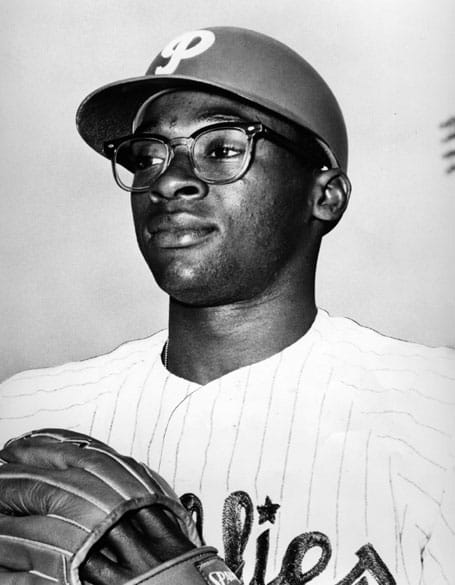

Dick Allen. Photo courtesy: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York

Richard Anthony (Dick) Allen: Star hitter

Richard Anthony (Dick) Allen was the first African-American to play for the integrated Travelers baseball franchise in Little Rock. His 33 homers by a right-handed hitter remained a Traveler record for nearly forty years. Fans voted Allen the team’s most valuable player at season’s end. Opening night in Little Rock still featured the tension that the newspapers had hoped to avoid. Marchers, led by White Citizens’ Council leader Amis Guthridge, picketed the ballpark carrying signs that read, “Don’t Negro-ize baseball.” Governor Orval Faubus, a nationally known opponent of school integration, threw the game’s ceremonial first pitch before a standing-room-only crowd of nearly 7,000, including about 200 black fans. As the national anthem played before the game, out in left field, the Travelers’ first black player repeated the twenty-third Psalm to himself. Allen was called up to Philadelphia in September 1963 to begin a fifteen-year career in the major leagues.

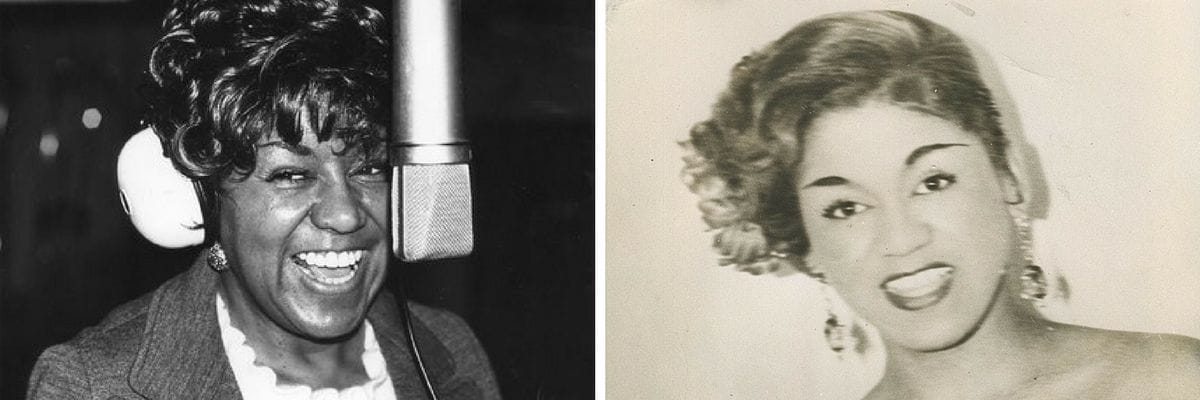

Al Hibbler. Photo courtesy: Billie Abbott

Al Hibbler: Celebrated singer

Jazz and pop singer Al Hibbler was the first blind entertainer to gain national prominence and was the first African American to have a radio program in Little Rock. He sang with the Duke Ellington Band for eight and a half years and made eighty-two recordings before launching a solo career. Hibbler made several Billboard pop hits—“Unchained Melody,” “He,” “After the Lights Go Down Low,” “11th Hour Melody,” and “Never Turn Back.” Hibbler’s version of “Unchained Melody” was the featured song in the movie Unchained, and he sang the title song in the movie Nightfall. Hibbler also became a prominent figure in the civil rights movement, marching with Martin Luther King Jr. and being arrested for civil disobedience in New Jersey and Birmingham, Alabama. His career waned because of his involvement in the movement, but Frank Sinatra signed Hibbler as one of his first solo artists on Sinatra’s Reprise label. Sinatra called Hibbler and Ray Charles his “two ace pilots.”

Brig. General William Johnson. Photo courtesy: U.S. Air Force photo by Master Sgt. Jeff Walston

Brig. General William J. Johnson, Ret.: Esteemed general

William J. Johnson became the first African-American general in the history of the Arkansas National Guard. Johnson served in the Arkansas National Guard for thirty-six years before his 2012 retirement. He is the first African-American General in Arkansas, the first African-American Deputy Adjutant General in Arkansas and the highest ranking African American in the Arkansas National Guard. General Johnson led more than 10,000 members of the Arkansas Army and Air National Guard and was in charge of the preparedness for domestic operations and homeland security in Arkansas. Johnson has received many awards and decorations, including the Legion of Merit Medal, Meritorious Service Medal with Three Oak Leaf Clusters, Army Achievement Medal, Army Physical Fitness Badge, Arkansas Distinguished Service Medal, and Arkansas Army National Guard General Staff Badge.

For more Arkansas Black History Firsts, click here.

*Factual information from these sites was used in the development of these historical and biographical briefs.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

[…] https://onlyinark.com/culture/arkansas-black-history-firsts/ […]

[…] https://onlyinark.com/culture/arkansas-black-history-firsts/ […]

[…] For more Arkansas Black History Firsts, click here. […]

Who was the first Black female to do a commercial in Little Rock? Someone said Channel 4 there was the first channel around 1974. Seems it aired around midnight during Soultrain for Armadillo’s hand. We need encompass all firsts in areas of progressive change.

Who was the young girl who helped to rid the law preventing

young girls from returning to school after pregnancy in September 1967 thereby going to Westside Jr. High then changing the school law that prevented full participation during her senior year at Hall High before graduating and proceeding on to UALR? Who was she?