Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

Off of winding Arkansas Highway 23 in Madison County lies tiny Brashears Cemetery. A series of stone coffins are scattered among tombstones and memorials that line the open field. Though lichen covers the lids of these aboveground crypts, and their shapes are reminiscent of the Egyptian sarcophagi of ancient kings buried in pyramids, you’ll find no mummies inside. In fact, these stone coffins never held bodies at all.

No gravestones accompany the stone coffins, and no one is left to tell us who made them and why they placed empty coffins in the cemetery. People were buried beneath them, though, so these empty stones on top are perhaps just a reminder of death in general or perhaps a hope that the stone coffins would remain empty in the next life.

Cemeteries, more than any other place, are a reminder that life on Earth is temporary and that death eventually comes for everyone. It’s written on the gravestones of loved ones; these markers are an attempt to honor and remember family and friends. They also remind us of our state’s past and the people who lived before us.

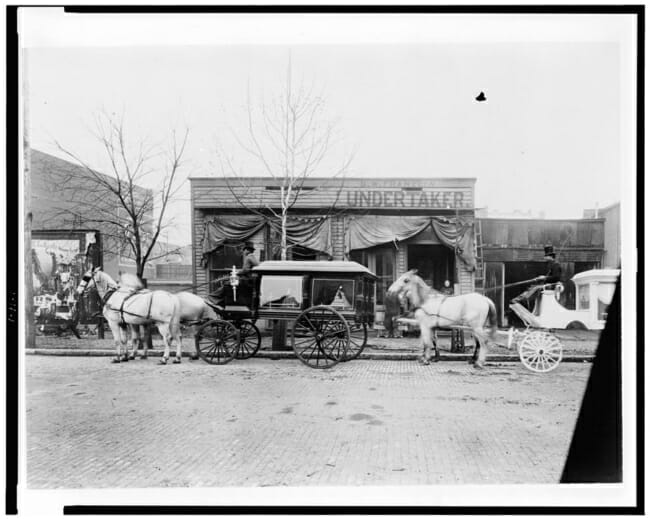

When Arkansas was a young state, burial rituals were different from today’s customs. A few funeral homes existed, but not many before 1900. Ruebel Funeral Home in Little Rock claims it is the oldest funeral home in the city, serving the area since 1901. Embalming still wasn’t a common practice in many areas, although it was used during the Civil War to preserve the bodies of deceased soldiers as they were shipped back to their home states for burial.

When a family member or neighbor died in Arkansas, it was common for friends and neighbors to immediately stop all work and help the family prepare for the funeral. The body had to be measured, and the wooden coffin made. The local carpenter usually took on this responsibility. Then family or friends, usually women, washed the body and put the deceased in clean clothes, or occasionally they quickly made a new outfit for burial. That night, family and friends would perform a “wake,” where they sat with the body all night until the coffin was ready. People didn’t leave a dead body alone. This was one of the cultural norms at the time. You might remember hearing stories from grandparents or great-grandparents about sitting through a wake or of a family member attending one.

Du Bois, W. E. B. (1899) Horses and carriages in front of funeral home of C.W. Franklin, undertaker, Chattanooga, Tennessee. Chattanooga Tennessee, 1899.Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

A typical funeral was held in the front parlor if the family had this small front room. Though it’s not the custom everywhere, in Arkansas, it was normal for funeral-goers to view the body one last time and friends and family would arrive to do so. Several superstitions surrounded death and burial. One was that a dead person should not pass through the same door as a living person. For this reason, a body was carried out of the house by a side doorway. In wealthier homes, this “death door” was included on purpose and was only used for removing deceased family members from the house.

Burials took place quickly in those days, but it was common for people to stay at the graveside until the coffin was completely interred in the ground. Many believed the superstition that if you left the graveside before this, someone else would die. Gravestones would later be installed, and inscriptions could be lengthy, with poetry or words to remember the deceased. It was far more common for relatives to visit the grave every year on Decoration Day to clean the graveside, read the inscription and leave flowers.

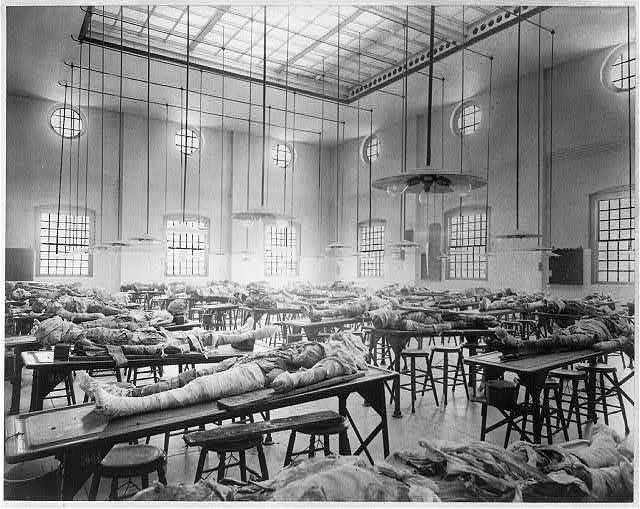

After the funeral, though, the graves didn’t always remain undisturbed. Graverobbing is an old practice, as opportunists took the chance to dig up recently buried corpses in search of valuables left with the body or even to steal the body itself. Medical students in the nineteenth century needed cadavers to dissect and study, but at the time, not many people donated their bodies to science, so the practice of graverobbing became common. “Body snatchers” snuck into cemeteries at night to find new graves, steal the bodies and sell them to medical colleges.

In 1873, the Arkansas legislature, aware of the problem, authorized legal dissection of bodies that were lawfully obtained, an attempt to quell graverobbing. Still, medical colleges had to find ways to obtain bodies. Many of these came from prison inmates who died, poor people whose bodies were unclaimed or whose relatives were too poor to pay for burial. Still, the practice of donating bodies to science didn’t become common until the twentieth century, and grave robbing continued.

In Arkansas, this practice disproportionately affected the Black community as well as poor families. People began taking steps to prevent robberies. Rich families built mausoleums and tombs, which were harder to break into, or they chose more elaborate monuments and sculptures to place over the graves. Poor families covered the graves in gravel so if they were disturbed, it would be easily noticed, or they buried branches in the soil to make it harder to dig up. In 1991, the state enacted the Arkansas Burial Law, which makes it illegal to disturb graves or sell human remains.

It’s possible the empty stone coffins on top of burial sites in Brashears Cemetery were another means of preventing grave robbers from stealing the remains of loved ones. Whether that was their purpose or it was simply a way of honoring the deceased loved ones, the empty coffins remind us of Arkansas’s connection with the living and the dead.

To learn more about burial customs in Arkansas, read “Gone to the Grave: Burial Customs of the Arkansas Ozarks, 1850 to 1950” by Abby Burnett.

Header Photo of the False Crypts at Brashears Cemetery by Marcus O. Bst via Flickr.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Kimberly Mitchell

The XXV Winter Olympics concluded this February in Italy, and one of the...

Scott Fitzgerald never forgot the feeling of freedom he got from biking...

Trains revolutionized the United States in the 1800s. People and goods...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment