Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

There’s no disputing that Arkansas’s early history as a territory and state was sometimes fraught with danger and criminal activity. Still, not many Arkansans today know that in 1842 the Little Rock mayor himself was arrested as the ringleader of a criminal gang operating inside the state. The arrest and subsequent trial were the talk of the town and state for much of 1842 and 1843.

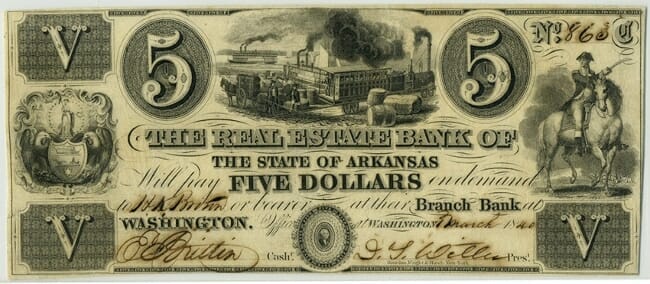

After Arkansas became a state in 1836, those in power were still discussing how the state would function, and these decisions weren’t always popular or peaceful. The first official act of the legislature after statehood was the establishment of the Real Estate Bank of Arkansas. The state controlled this bank from 1836 to 1855, and its existence was associated with corruption and became a point of political tension between Arkansas lawmakers. In fact, it led to a death in 1937 when an Arkansas representative from Randolph County, Joseph J. Anthony, made a passing sarcastic comment about House Speaker John Wilson’s involvement with the bank. Wilson was also Real Estate Bank’s president. After the session ended, Wilson attacked Anthony with a Bowie knife and killed him on the legislature floor.

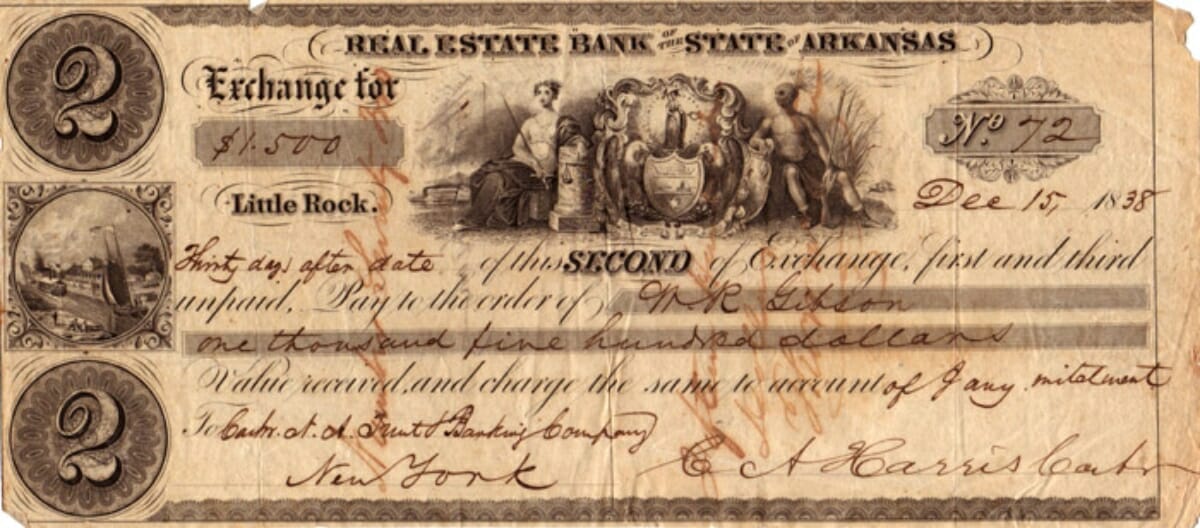

Wilson was eventually found “guilty of excusable killing” and served no jail time for the murder. He was expelled from the legislature but returned in 1842 as a representative, where he attacked another member of the legislature during a debate over the Real Estate Bank. The bank was continuously accused of mismanaging funds and issuing too many banknotes, which flooded the market and caused the notes to depreciate in value. The relationship between the bank and Arkansas legislative members was also under scrutiny. Like Arkansas Real Estate Bank, Arkansas State Bank was created in 1836 and was meant to serve the public and be the depository for state funds. The bank struggled from the beginning as the country entered a depression in 1837, likely fueled by the number of banks across the nation issuing banknotes.

It was in this time of financial and political uncertainty that Samuel Trowbridge arrived in Arkansas. Trowbridge was from Chicago and leased the American Hotel in Little Rock in 1939, which was later more well-known as the Anthony House and stood on the corner of Markham and Scott streets. Trowbridge was often surrounded by “newcomers from abroad, who never seemed to have anything particular to do except to frequent the hotels and bar rooms,” according to Judge William F. Pope, who leased the hotel to Trowbridge. The man from Chicago also found his way into politics, and in 1842, he was serving as Mayor Pro-Tempore, otherwise known as Deputy Mayor. Mayor John Widgery resigned from his position in April of 1842, and Trowbridge won a special election in May to become the new mayor of Little Rock just three years after his arrival to the state.

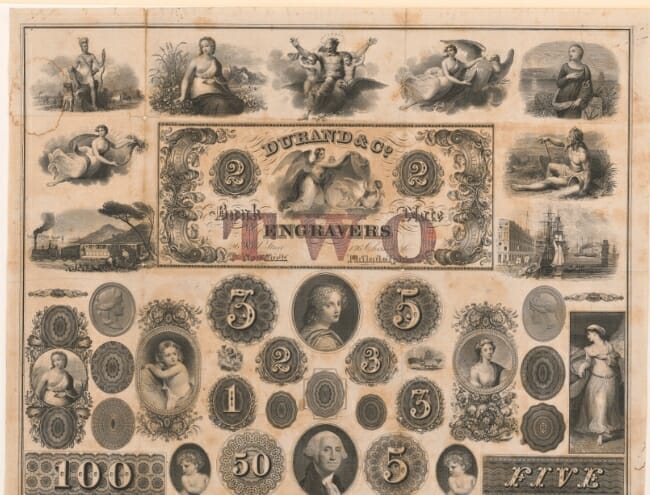

Meanwhile, and of course unknown to most, Samuel Trowbridge was also the mastermind behind a counterfeiting ring. In 1839, coinciding with Trowbridge’s lease of the American Hotel, he hired Francis Van Horne of the Arkansas newspaper the Gazette and used Van Horne’s knowledge of printing to make counterfeit banknotes. In 1841, Van Horne worked for The Times And Advocate and stole pieces of type from the newspaper’s office to continue the operation. The banknotes flowed into circulation in Arkansas, especially across Pulaski and Crawford County. In 1841, Van Horne moved to Van Buren to found the newspaper the Arkansas Intelligencer alongside fellow Trowbridge counterfeiter Thomas Sterne.

While Samuel Trowbridge continued as a businessman and politician, his criminal operation ran right out of his own house. Trowbridge had assembled a team with excellent craftsmanship capable of producing counterfeit U.S. coins, bank notes from other states and notes from the Little Rock city corporation. These included the mayor’s signature. While Trowbridge was mayor, he signed off on these notes himself.

The counterfeiters operated smoothly, but it wasn’t their craftsmanship that was their downfall. In April of 1842, the Real Estate Bank bank failed and went into receivership. Justice of the Peace J.D. Fitzgerald was keeping around $14,000 in Real Estate Bank notes in a safe in his office in August of 1842 when the safe was broken into and the money stolen. Trowbridge’s wife and two friends who were also wives of fellow gang members just happened to spend $13,000 worth of Real Estate Bank notes on a shopping spree at Little Rock store Adamson & Prather’s. The women purchased new hats and other dry goods. They didn’t realize the bank notes were marked for tracking their use and were the same notes stolen from Fitzgerald’s safe. Shortly afterward, Samuel Trowbridge and Francis Van Horne were arrested, and other arrests followed as investigators began to make the connection between Trowbridge’s gang and crimes in the area over the last four to five years, including a jewelry store robbery. This, of course, was as long as Trowbridge had been in Arkansas.

The trials of Trowbridge, Van Horne and other members of the gang were covered in detail in the local papers and riveted the city and state with their sensationalism. Trowbridge was eventually sentenced to 21 years in prison, and nearly everyone associated with the gang also received prison time. Trowbridge’s sentence was reduced to five years by Governor Archibald Yell. While many in the state were incensed by the governor’s pardon, acting Attorney General Frederick Trapnall claimed the reduction was in exchange for information on the many members of Trowbridge’s gang operating in the state as well as the location of counterfeiting equipment.

What happened to Samuel Trowbridge after he served his sentence is lost to history, but his brief reign as the mayor of Little Rock, and longer reign as the leader of a criminal gang, still hold an interesting place in Arkansas history.

Photos of Real Estate Bank Notes Courtesy of the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Central Arkansas Library System, Gibson Family Papers via the Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

One response to “Samuel G. Trowbridge: Arkansas Mayor and Counterfeiter”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

[…] Samuel Trowbridge: Mayor and Counterfeiter […]