Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

I’ve always been fascinated by artists and musicians who grew up in the south. I adore stories about Loretta Lynn’s journey to fame. I shook her hand once during a performance at the Grand Ole Opry and to this day it is one of my most prized memories. I admire Louis Armstrong, born in New Orleans, the grandson of slaves. I think what fascinates me the most about these individuals is not necessarily their stardom, but their rise. There is something special and particularly inspiring about the rise to not necessarily riches or fame, but the rise of a fellow human being to their fulfilled purpose. Then again, I think most of us are fascinated by that. We all seek to do that in our everyday, ordinary lives. Some of us write, others paint, others bake cakes and garden. But it is those things, those talents and loves, that give us a reason to wake up in the morning. It is those things that sets us apart, that makes us “more than” just our desk jobs or commutes. These are the things that make us all rise.

Although like Louis and Loretta, some people do it a little grander, with a little more style and a little more aplomb. And that brings me to Ms. Cynthia Scott.

Photo credit Daniel Dugan

When I first discovered Cynthia Scott as a fellow Arkansan, I was fascinated to read about her life that began as a preacher’s daughter in El Dorado, her civil rights bravery, her music career spanning decades, and touring with Ray Charles. Born in 1951 in El Dorado, Arkansas, to Reverend Sam Scott and Artelia Scott, she was one of 12 children in her family. She credits her upbringing in the church as the starting point for her love of music and singing. Born at midnight, she told me she was very nearly born and delivered in the church building.

“I practically had to live in a church somewhere, sometimes morning, noon, and night. I heard the music early on, and I believe the best music came out of the holiness/sanctified church. Some people call it Pentecostal now. The church teaches you pulse and a music that is led by the spirit. At least that is the way I felt. “

But Cynthia’s love of music expanded beyond the walls of the church, and into the secular world. As with many religious people at the time, secular music was deemed “of the world” and disapproved. Cynthia’s parents did not support any music that was outside the church, until one day her mother had a change of heart.

“My mother put her foot down and let me be in a high school band with two other singers, Jeanette Malone and Carolyn McDuffie, with an all-white band called The Funny Company, Featuring the Sisters of Soul. We all attended El Dorado High School.”

Cynthia credits her mother for allowing this, and for encouraging her to pursue her passion.

“My father did not come on board with my music until many, many years later. But my mom opened that door for me. I am so grateful. I have no idea who I would be today, or if I would even be alive if I had not followed my passion for music.”

Cynthia’s passionate personality isn’t just limited to music. The late 1960’s were a time of great social unrest and upheaval with the Vietnam War, and race relations in the United States were at a fevered pitch with the Washington DC riots, the Fair Housing Act, and the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. And it was during this time period, a month after her high school graduation, that Cynthia bravely entered the annual Miss El Dorado pageant, an exclusively white pageant.

“It was like an out of body experience because to this day, I can’t tell you why or what possessed me to walk down Liberty Street, turn right on Northwest Avenue, and walk into the Holiday Inn to register for that pageant, knowing that it had never been done before. It was like a calling.”

Historically, beauty pageants in the United States were largely segregated. For the first 35 years of the Miss America pageant, all non-white women were barred from participation. In response to this, the Miss Black America Pageant was founded in 1968 in an effort to celebrate black beauty. It wasn’t until 1970 that a black contestant competed in the Miss America pageant, and it wouldn’t be until 1984 that Vanessa Williams would wear the Miss America crown.

Cynthia, even at the young age of 18, and in the small town of El Dorado, decided to do her own part to shatter the race and beauty barrier of her hometown pageant, despite her fears and apprehensions.

“I had been reading about the pageant for years, but I also knew that black girls were not wanted in a beauty competition. If they had said “go home little girl, we don’t take your kind here” I would have just walked out and never said a word. I was told later that the pageant officials thought I was sent in by the government as a decoy to see if they were discriminating. Which is why, after much discussion, they gave me an application to fill out.”

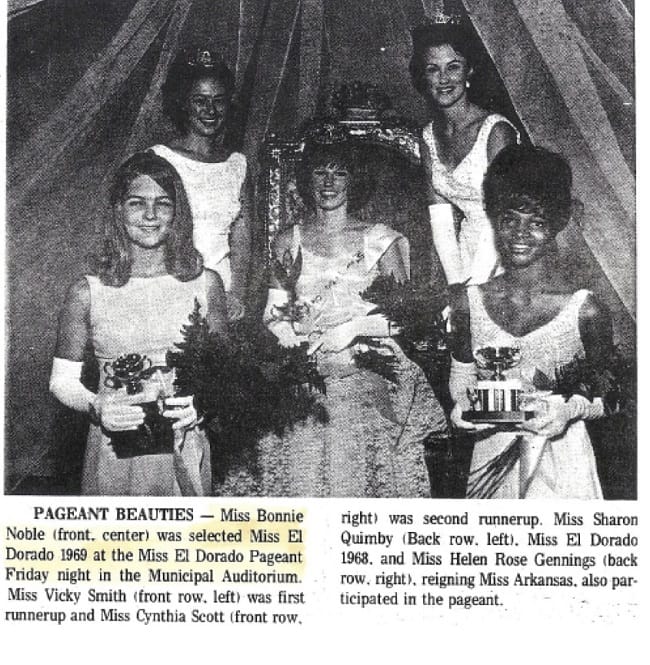

Without the knowledge or approval of her parents, Cynthia entered the pageant and proceeded to buy a $1 pink lace bikini at the local dollar store for the swimsuit competition. She won the second runner-up, a feat that mysteriously disappeared from history when the microfilm depicting the day she made the front page of the El Dorado News-Times vanished. Years later, a friend gave her a newspaper clipping they had saved. It is, she believes, the only remaining evidence of that day. Cynthia’s thoughts on her bravery and the stand she took that day are humble and reflective.

“The question in my mind has always been, who really won? It is pretty interesting now that I look back at it, and the tumultuous times during that era. Listening to the news today, it seems we have not come as far as we thought.”

In 1971, Cynthia became one of the first African American flight attendants for Texas International Airline and moved to Dallas. And while some women had dreams of soaring above the clouds, Cynthia became a stewardess by a series of humorous, happenstance events. When picking up airline tickets at a travel agency for her boss (Herb Fox who later became president of Murphy Oil), she noticed an application for a stewardess position in Dallas. With the interview came a free airline ticket, and she very much wanted to get to Dallas, but not because of a job.

“I really wasn’t trying to be a stewardess. I was trying to get a free ticket to Dallas to see a boy I liked. I filled out an application and got a letter in the mail saying, “You are scheduled for an interview in Dallas.” My ticket was sent. When I arrived, I had planned to meet this boy I liked, but the flight was late, and he was told the flight had already landed. He thought I changed my mind, so he left. This was pre-cell phone days.”

Instead of meeting up with her crush, Cynthia was greeted by an airline official who took her to an office and gave her a written exam. She was measured by height and weight.

“Next thing I know I was hired and sent to Houston for training. Did I mention that I hate flying and still do? I didn’t make it off my six-month probation because I reported a pilot for sexual harassment and was fired.”

After being propositioned by a pilot for sex and reporting it, Cynthia’s supervisor’s reaction was, “Who do you think they will believe, you or the pilot?” She was subsequently fired. This would not be Cynthia’s last experience with sexual harassment, but she has valuable thoughts and advice for younger women.

“Back then there was no word like “sexual harassment” that you could file. It was considered life and you dealt with it. I wish I could have sued back then. Today I have no patience for it, trust me. I still have to fight to keep some people in their place, even as an old broad. But there is something that comes with getting older. You know you don’t have to deal with some of the crap and you don’t. I have no patience. All women should take a stand and report it, but only if it is true.”

Amidst all her youthful life changes, music continued to play a central role in her life. While living in Dallas and working at General Motors/United Delco, Cynthia continued to sing in clubs and had the opportunity to perform with jazz musicians such as James Clay, Marchel Ivery, Claude Johnson, and Red Garland. She eventually got an audition at the Candlelight Club and was given a job as a singer by Joe Johnson. This was a job she credits with changing her life.

“Claude went on to play saxophone for Ray Charles. I had worked with a lot of musicians from Dallas by this time, and Ray hired a lot of musicians from Dallas. Texas has great musicians. I also knew one of the Realettes, Mable John.”

It was Cynthia’s passionate love of singing, and these connections, that led to an early morning phone call that changed her life.

“Ray called me at 5 a.m, and two weeks later I was in Finland.”

Cynthia went on to tour with Ray Charles for two years. She flew on his private plane and traveled the world. She was warned early on by John Bond (who was working with the television AGVA union), “Don’t be one of the Raelettes who let Ray.” As it would turn out, Cynthia was later fired due to another instance of sexual harassment. She later reminisced, “I got fired because I didn’t play ball with him.”

Despite this, Cynthia still admires her former boss, perhaps not for his moral fiber, but for his musical talent.

“I was in awe of Ray because he was so talented. The fact that he could sing a song every night and we never got bored hearing him sing. Every time it was something different, even with the same song. As a singer, you can easily get into a rut and go on automatic pilot. I saw him take the same song and create a new journey every night for the audience.”

Cynthia went on to describe tricks performers use to keep their performances fresh and unique every time. She noted that Ray employed these techniques.

“You pretend that the boy you love just kissed you, then you walk on stage and sing a song. The next night you pretend the boy you love just broke your heart, and then you go on stage and sing a song. You get two different performances. Ray may not even have been aware he was doing that, but he could change himself and his mood, and go anywhere he wanted with his performance.”

Cynthia currently performs a play called “One Raelette’s Journey” detailing this time in her life. It’s a one-woman 70-minute play with music. It won the Jerry Kaufman award for best playwright in New York City, and Cynthia wishes she could bring the play back to her home state of Arkansas.

“It’s hard to bring a play with music to any state. But I’d love to come back to Arkansas and perform it.”

After singing with Ray Charles she continued to perform with some of his band members: David Newman, Marcus Belgrave and Leroy Cooper, to name a few. She performed in Dallas until the 1980’s when she was asked to perform at Chelsea Place in Manhattan. She remembers, “I got to NY just under the wire. I got a taste of the magic musical period where Miles Davis was on the sidewalk.”

New York was a long way from the south, but as a woman who had done her part to integrate her hometown’s beauty pageant and the concept of African-American beauty, she found herself right at home in the Big Apple.

“I arrived in 1986, and I was walking down Broadway in the Times Square area, and I saw this big, beautiful bald black lady on a billboard. I think it was an advertisement for Kodak. It was the first time I had ever seen a black woman advertised like that. She was towering over Times Square, with her beautiful black skin for the whole world to see. And my first thought was, ‘I am in the right place.’”

Cynthia went on to hire a then-undiscovered Harry Connick Jr. as her pianist. A four-week engagement turned into three years. She went on to headline and was a featured vocalist at the Supper Club in Times Square. Her musical experiences read like a Who’s Who List. She’s worked with Cab Calloway and Lionel Hampton in their later years. She performed at the Lincoln Center with Wynton Marsalis, and with the Diva Jazz All Girl Big Band, the Andy Farber Big Band at the Lincoln Center, and with David Fathead Newman. She was also the first person to test the vocal sound in the Rose Room at the Lincoln Center.

When working at the Lincoln Center with her own band, the promoter, Todd Barkan, called her “Great Scott.” It was heartwarming and a little “full circle” as it hearkened back to her roots in Arkansas. Her first review of her performance in El Dorado was covered in the local paper with the title “Great Scott” on the front page. She remembers, “I loved it! How is that for making your last name really work for you?”

She went on to be a vocal teacher for City College of New York, and The New School. She continues to teach privately and utilizes Skype.

“I really enjoy it. I’m having the best time with my students. Time flies when you’re enjoying being a teacher.”

And while Cynthia now divides her time between Dallas and New York, she keeps a strong connection with Arkansas and her hometown. She often comes home to attend family gatherings or just to see old friends. Her nostalgia for home includes the bounty of south Arkansas fruit.

“A friend of mine had a great plum tree that produces the best plums. When I was growing up I was always warned not to eat too many or I would get a tummy ache. Never happened. The apricots in the city just don’t compare to El Dorado plums.”

And as a native Arkansan who has lived across the country and traveled the globe, she has advice for those of us willing to venture out into other areas.

“Go with an open mind and be ready to learn and change. But hold on to those southern values and manners. They are needed no matter where you go.”

In addition to her one-woman musical, One Realette’s Journey, Cynthia has also released five albums in the course of her career: I Just Want to Know; Boom Boom; Live in Japan With Norman Simons Trio; A La Carte: Live at Birdland; Storytelling: Live at Birdland, and Dream for One Bright World. For more information on Cynthia, visit her website here. She will also be performing at the 25th Anniversary of the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame in Little Rock on October 28th (where she was inducted in 2016).

After our phone interview, what struck me most about Cynthia was her humility and down-to-earth sense of humor. And after years of following the stories of southerners who came from small towns and created lives built on adventure, travel and talent, it inspired me to speak with her. Louis Armstrong was quoted as saying, “Musicians don’t retire; they stop when there’s no more music in them.” If this is true, which I suspect it might be, there is no retirement in sight for Ms. Cynthia Scott.”

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

One response to “Spotlight on Cynthia Scott: Ray Charles, Pink Bikinis and Jazz”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

[…] such as producer and former Prince keyboardist Morris Hayes, Grammy-nominated jazz vocalist Cynthia Scott and award-winning poet Dr. Haki Madhubuti—who will perform a special piece for the first time […]