Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

In 2002, after more than 40 years in baseball, Hoss Bowlin was inducted into the Hall of Fame. Bowlin was honored by the Athletic Hall of Fame of West Alabama University, where he had been a successful baseball coach for 14 years. Although his induction was not held in Cooperstown, New York, the honor bestowed on Bowlin paid tribute to a distinguished baseball career. Bowlin’s professional and personal adventures in baseball reveal a man of admirable courage and fierce determination. Between the back roads of Greene County, Arkansas, and that induction ceremony, baseball had taken Hoss Bowlin from personal crisis, through American social history, to a “Cup of Coffee” with Reggie Jackson.

Lois Weldon Bowlin was born in December 1940 in Paragould, Arkansas, and raised in Pumpkin Center, about ten miles west of town. His mother had planned to name a daughter Lois, and, according to Bowlin, she liked the name well enough to give it to him. Bowlin earned the incongruous nickname, “Hoss,” not from his size but for his inclination to race the family horses. He preferred Hoss to Lois or Weldon. Life was tough on the cotton farm in Northeast Arkansas. Sugar Creek served as the swimming hole and bathtub, and interfamily baseball games were the main entertainment.

Youth baseball opportunities for rural youngsters like Bowlin were not easily accessed in the 1950s, but young Hoss excelled on travel teams in nearby Paragould when he was old enough to drive the farm truck. In the spring of his senior year, Bowlin attended a professional tryout. He was the fastest player who participated that day, and his baseball skills impressed the pro scouts. The little country kid from Arkansas was fast, smooth in the field, and a good contact hitter, but at 5’7’ and barely 150 lbs., his size discouraged most major league teams. The St. Louis Cardinals decided to take a chance and offered the 18-year-old a $2,000 bonus and a trip to spring training. That was certainly enough. Like so many Arkansas youngsters, being a St. Louis Cardinal was a dream come true for a kid from Greene County, Arkansas.

Bowlin enjoyed encouraging success in his first year of pro baseball. He performed well enough in Hobbs, New Mexico, to make the All-Star team. Unfortunately, his work in the following three seasons was not impressive enough for the Cards to consider him a major league prospect. Although disappointed, Bowlin probably should not have been surprised when St. Louis traded him to the Kansas City A’s in the winter of 1962.

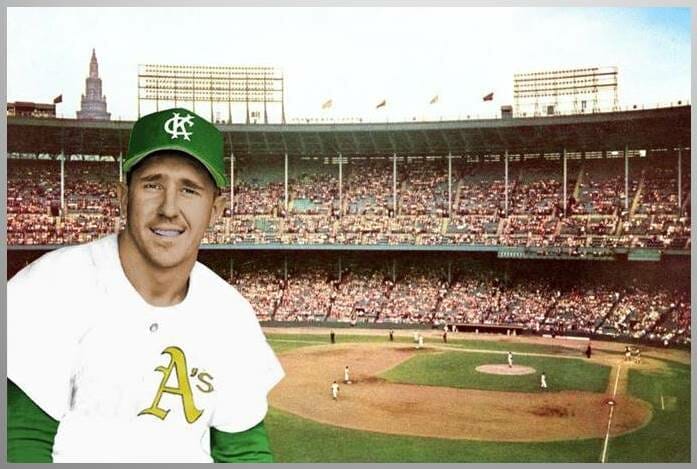

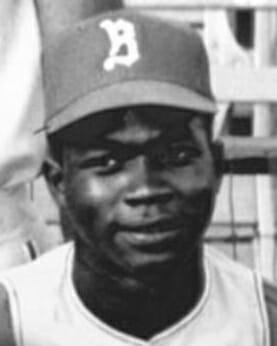

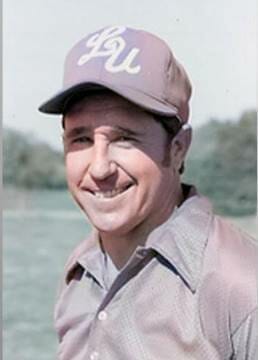

Hoss Bowlin 1964

Hoss Bowlin 1967

Hoss had been languishing in the lower minors for the Cardinals. The A’s promoted him immediately to their Class A team in Lewiston, Idaho, where he hit .287 and led the team in hits, walks and runs scored. Unlike the Cardinals, the A’s saw Bowlin as a potential top-of-the-order major league prospect. Failing to get attention in the Cardinals’ minor leagues seemed now to be a fortuitous turning point in his career. Ironically, the excitement of a new beginning was about to become the low point of Bowlin’s life.

What he had passed off as a nagging late-season injury turned out to be cancer. Suddenly, his invincibility of youth was replaced by thoughts of a career-ending and life-threatening new reality. Bowlin had the A’s attention, but as 1964 began, he was recuperating from serious surgery back in Greene County. Doctors were not optimistic, but Bowlin was determined.

Miraculously, by spring training, Bowlin was back in the A’s minor league camp. Bowlin somehow remained a relevant part of KC’s plans, thirty pounds lighter and weakened by illness and surgery. He was promoted to Birmingham, the new AA team in the A’s organization, as part of owner Charlie Finley’s great social challenge.

The Birmingham Barons were one of the most storied franchises in the minor leagues. But in 1961, when major league baseball passed the rule that all minor league teams would integrate, the Barons folded rather than comply. A native of Alabama, Finley was determined to bring back the Barons. The A’s owner intended to change both the losing baseball culture in Kansas City and the segregated baseball culture in Birmingham.

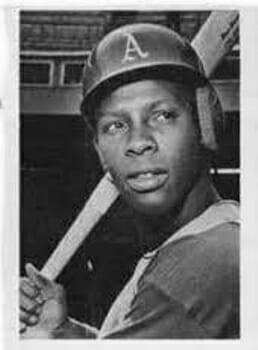

Bert Campaneris

Blue Moon Odom

Tommie Reynolds

Hoss Bowlin was recovering from a serious illness and fighting for his baseball life. He had little interest in being part of a civil rights test case, but that role was included in the job description for a Birmingham Baron in 1964. Bowlin not only made the team, but he also started 136 games of a 140 game season as the Barons’ second baseman. In most of those games, his teammate at shortstop was Bert “Campy” Campaneris, one of Finley’s prized prospects and part of the owner’s bold integration move. Campaneris, a native of Cuba, was joined by several other Latino prospects and African American outfielder Tommie Reynolds. Later Finley added Johnny “Blue Moon” Odom, a high school pitching phenom from Georgia, who signed for $75,000, the largest signing bonus up until that time for an African American prospect.

The 1964 Barons played baseball almost as an aside to a continuous maelstrom of social turbulence. Threats, boycotts, segregated hotels on the road, and raucous fans got far more attention nationally than the Barons, who finished one game out of first place. Hoss Bowlin had slipped to .242, but he was just happy to be healthy and play baseball in retrospect. Campy, Reynolds, and Blue Moon Odom had all been promoted to the A’s by season’s end. Hoss Bowlin stayed behind in the minors.

Hoss remained in the higher levels of Kansas City’s minor league system, as Charley Finley promoted the future members of the World Champion A’s of the early 1970s. By 1967, although Bowlin was only 26-years-old, he was past his best years in baseball. He was undoubtedly the most surprised minor leaguer to get the call to report to the major league team in Kansas City after the Baron’s season ended. On September 16, 1967, he found himself in the starting line-up of the Kansas City Athletics.

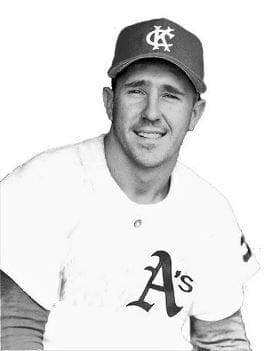

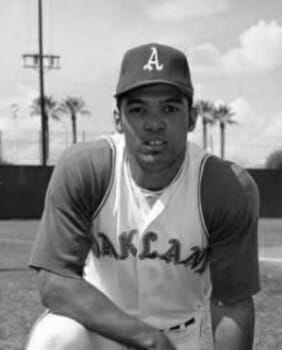

Hoss Bowlin 1967

Reggie Jackson 1967

Bowlin singled in the fourth inning and was on second when Reggie Jackson sacrificed a bunt. Jackson, who would become one of the game’s most prolific sluggers, actually recorded his first sacrifice bunt before he hit his first home run the next day. Hoss witnessed Jackson’s historic first homer from the on-deck circle.

After two major league games, Hoss Bowlin’s nondescript major league career was over, and his Hall of Fame career was about to begin. Although he would never be a major league star, Bowlin had earned the respect of the baseball world. He knew the game, and his character, courage, and baseball smarts had been noticed. One of those following his career was fellow Arkansan Paul “Bear” Bryant, who was not only the University of Alabama football coach but also the athletic director. Bryant was looking for a graduate assistant to help his baseball coach, former major league great Joe Sewell.

Hoss Bowlin, Livingston State Coach

Bowlin had no college degree that qualified him to be a graduate assistant, but Bryant could handle that kind of small obstacle. Bowlin’s family could live in a married student apartment and eat free with the players. Madelyn Bowlin, Hoss’ wife, would have a teaching job waiting when they moved to Tuscaloosa. In Alabama, Bear Bryant got things done and hiring Hoss Bowlin was one of those things.

Bryant’s plan paid off immediately when Alabama, led by Joe Sewell and his new assistant, won the Southeastern Conference baseball championship in 1968. He finished his degree at Alabama in 1971. After one season of minor league managing, Bowlin was hired as head baseball coach at Livingston State University, now the University of West Alabama. He coached Livingston State for 14 seasons and guided the Tigers to 92 conference wins and an appearance in the Division II College World Series in 1976.

Lois Weldon Bowlin lived one of those movie script lives that opened with a hardscrabble life in the cotton patches of Eastern Arkansas. He later moved through a life-threatening illness, civil rights struggles, and a Cup of Coffee in major league baseball. After he retired from coaching, Bowlin continued to live in Livingston and later became director of parks for the city. Bowlin’s West Alabama Athletic Hall of Fame induction in 2002 did not end his recognition by UWA baseball. In April 2017, the new digital scoreboard at Tartt Field, home of the Tigers, was designated as Hoss Bowlin Scoreboard.

———

Author’s note: Weldon Bowlin passed away on December 8, 2019.

Link – https://www.bumpersfuneralhome.com/obituary/hoss-bowlin

Photographs courtesy of Bowlin family

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Jim Yeager

In 1942, the Americans Tom Brokaw would later celebrate as our...

In 1920, the winter days between Christmas and New Year’s Day promised...

The 1951 baseball season arrived in Little Rock with little cause for...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment