Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

You probably have a bottle of apple cider vinegar in your pantry. It’s a standard ingredient found in most households. Many people use it in salad dressings and marinades or to make “buttermilk” when making homemade biscuits. Some people swear by its supposed health benefits, while others use it to make homemade cleaning solutions. From soothing sore throats to shining countertops and adding flavor to food, this versatile vinegar has been a trusted staple for generations.

Many Arkansans may not realize our state once played a significant role in the production of apple cider vinegar. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, northwest Arkansas was one of the country’s top apple-growing regions, shipping boxcars of fruit across the nation. Benton County was nicknamed the “apple orchard of America” and had over 40,000 acres of apple trees. In addition to orchards and packing sheds, there were said to be more than fifty distilleries that produced cider, brandy and vinegar throughout northwest Arkansas, including several large factories in Rogers and Prairie Grove.

Making vinegar was a great way to utilize apples that didn’t meet market standards. Records from that era are spotty at best, but indicate that vinegar was made from both fresh apples and dried apples. Essentially, vinegar makers used whatever apples they had on hand.

Perfect fruit went to market, but the bruised and misshapen ones, called “culls”, were destined for cider presses or the evaporators. In good harvest years, when apples were plentiful, producers might dry the excess to preserve them for later. One such apple evaporator was located in Lowell, and many apples were sent here to be dried for more extended storage. When needed, these dried apples could be soaked in water and pressed again to make juice for fermentation.

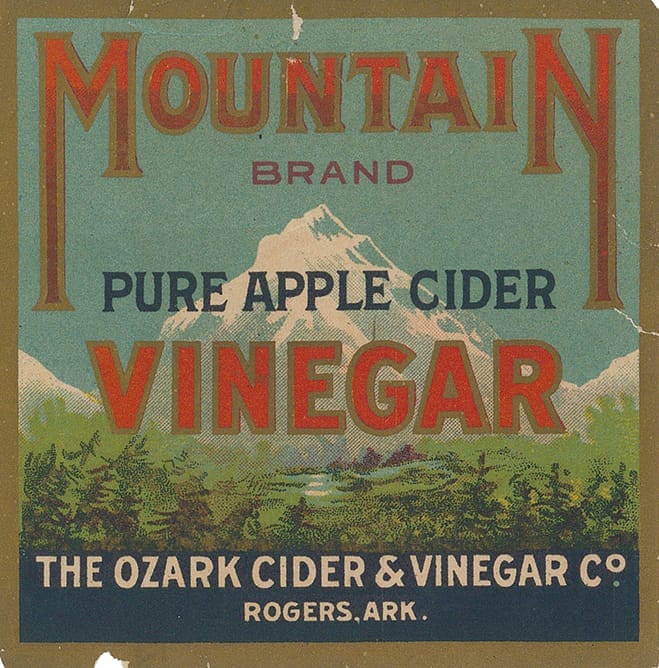

By the early 1900s, vinegar production had become more industrialized, especially in towns like Rogers and Prairie Grove, where sizable factories handled tons of local apples. Rogers Cider & Vinegar (also known as Ozark Cider and Vinegar and Jones Brothers Vinegar) opened in 1905 and was a leader in vinegar making for nearly 95 years. During its prime, the plant processed 700,000 bushels of apples and shipped out more than 500 railcar loads of vinegar per year.

Such quantities were possible due to advances in technology. Instead of hand-pressing apples on the farm with a small press, factories used large mechanical grinders and presses to crush tons of fruit at once, collecting the juice in huge wooden vats or steel tanks. The cider was left to ferment naturally or with added yeast until it turned into alcohol. It was then exposed to air in shallow “acetifying” tanks where bacteria converted it into vinegar. Workers regularly tested its sharpness by taste before filtering and bottling it for sale. Many factories ran year-round, using fresh apples, stored cider, and often rehydrating dried apples to stretch their supplies.

The practice of using dried fruit was widespread, but that all changed when federal food laws tightened following a landmark Supreme Court case in 1921. After a lengthy trial brought against a New York cider maker, it was determined that vinegar made from dried fruit could no longer be labeled “apple cider vinegar.” It was more of a mislabeling issue than a health and safety issue, but it upended the industry and forced many manufacturers to change their practices.

Changes in government regulations, catastrophic crop loss caused by diseases like fire blight, apple scab and bitter rot and early-season frost brought Arkansas’s apple industry to a screeching halt in 1927. Apple production dropped dramatically over the next ten years, and many orchards, evaporators and distilleries went out of business. Jones Brothers Vinegar managed to stay afloat and, although it changed hands many times over the years, continued to produce vinegar until the plant closed in 2001.

Apple Cider Vinegar production in Arkansas largely ceased after the Rogers plant closed, except for a few small businesses. Although they aren’t making apple cider vinegar, Lost in the Ozarks in Lead Hill makes small batches of fruit vinegars, including persimmon and blueberry. You can find their products online at LostintheOzarks.com.

Cover photo courtesy of Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Central Arkansas Library System. Use with permission.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Julie Kohl

I read a lot of historical fiction, and one thing that always catches my...

Our fridge has an ice maker, but it often “goes on vacation,” as we...

I was a little late to the podcast party. I wanted to love them, but...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment