Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

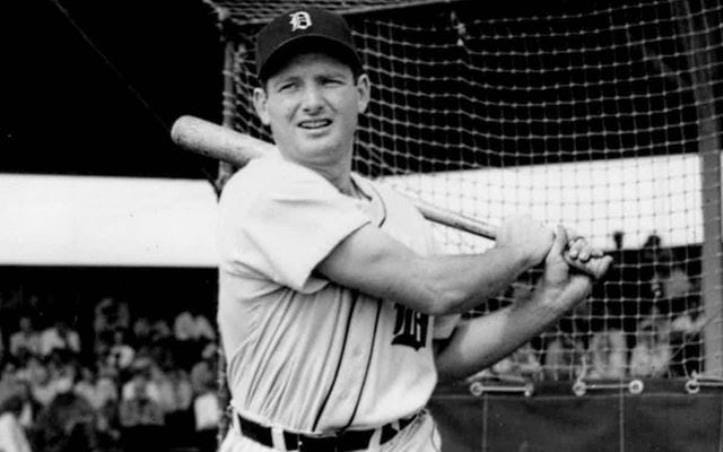

Posed batting of Detroit Tigers George Kell, 1951

Reflecting on his Hall of Fame career, George Kell revealed his conflicted feelings as he waited in the on-deck circle for his last at-bat in the 1949 season. It was a turn at bat that he did not want to happen. “I really didn’t want to bat, but I couldn’t see putting in a pinch hitter for me in that situation,” Kell recalled. He would be fourth up for the Tigers in the bottom of the ninth, and sensing Kell’s dilemma, manager Red Rolfe, asked if he would agree to a pinch hitter if the Tigers got a runner on and reached his spot in the batting order. Anyone who knew George Kell would have been confident in his reply, “No, I’ve got to hit.”

The last day of the season had started with the great Ted Williams leading the league with a .344 batting average and Kell three points back at .341. In Kell’s mind, the batting race was over. Gaining three points on the man some regard as the best hitter in baseball history seemed unrealistic, but in the late innings of that final game, the press box got the message that the improbable had happened. Williams had gone hitless. Kell’s two hits in three at-bats had given him a precarious lead, but an out in one more at-bat would certainly cost him the coveted batting title. When pinch hitter Dick Wakefield singled with one out, Kell took his place in the on-deck circle. Many major leaguers faced with the tough choice Kell faced that day would have opted for the pinch hitter and clinched the American League batting crown. That is not the way things were done in Swifton.

George Clyde Kell grew up in Swifton, Arkansas, the oldest son of town barber and highly regarded semi-pro pitcher, Melvin Clyde Kell. His father just happened to be the pitcher the town team needed when they recruited their new barber. Young George got his baseball start on that same town team. His father, also team manager, sent 12-year-old George in to play second base in the ninth inning of a July 4th celebration game the Swifton team had well in hand. George and his father thought it was a great idea, but his mother did not agree. George would later explain her actions with a familiar Arkansas description, “She threw a fit.” “What do you think would have happened if one of those big strong men had hit the ball at him,” Alma Kell asked angrily. “Well, George would have caught it,” Clyde Kell said proudly.

George graduated from high school in 1939 at age 16, and after a year at Arkansas State University, the Class D Newport, Arkansas, Dodgers signed the 17-year-old to his first pro contract in 1940. Kell hit a weak .160 in 48 games that summer in Newport, giving no indication of the major league hitter he would become.

However, the next year George Kell was a much different player. Although at age 18, he was the youngest player on the team and just one year out of high school, Kell batted .310 and led the team in most offensive categories. 1941 was a memorable year in his personal life also. On March 24, he married his high school sweetheart, Charlene Felts.

The Dodgers promoted Kell to the Durham Bulls the next spring, but the Bulls quickly gave up on the youngster, who in Kell’s words, “Did not look much like a prospect.” At 5’ 9” and about 180, the 19-year-old infielder may not have looked athletic, but that judgment was an error the Dodgers soon regretted.

After Durham cut him before the season began, Kell called home to tell Charlene that he had been offered a high-paying construction job and his baseball career was over. His wife had other ideas. “You are a ballplayer, not a factory worker,” Charlene reminded him. George later surmised that she had more confidence than he did. Despite the temptation to give up the game he loved, Kell hung around Durham until the Lancaster Red Roses came to town. Although the Bulls had just cut him, the club management made Kell sound good enough that the visitors, who were in need of an infielder, signed the discarded third baseman. In the process, George actually got a raise.

Kell would spend two excellent developmental years with Lancaster. His .396 batting average in 1943 earned a silver bat as the minor league’s batting average leader and a one-game promotion to the Philadelphia A’s. With big-league quality players in short supply due to service in World War II, George Kell was a major leaguer to stay.

As the A’s regular third baseman the last two seasons of the war years, George posted batting averages around .270, but only 55 of his almost 300 hits were extra-base hits. With many of baseball’s stars serving in the military, Kell was a singles hitter with little power and many unanswered questions about his future when those regulars returned from active duty. With those lingering questions about Kell’s major league value in mind, after 28 games of the 1946 season, A’s legendary manager Connie Mack traded his 23-year-old third baseman to the Detroit Tigers.

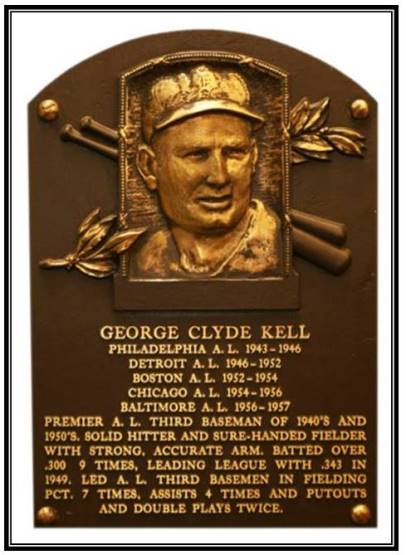

Although he was surprised and disappointed by the trade, leaving the hapless A’s and going to the first division Tigers, was one of the most fortunate events in Kell’s career. In his six-plus seasons in Detroit, Kell would be named to six consecutive American League All-Star teams, and lead the league in numerous hitting categories. Those accomplishments were highlighted by that American League Batting Championship that came down to that last at-bat in 1949.

While anguishing in the on-deck circle awaiting a turn at the plate that could cost him the tenuous lead for the batting average lead, fate intervened on George Kell’s behalf. With one out and a runner on first, Eddie Lake’s ground ball to short turned into an inning-ending double play. Kell had edged out Ted Williams in one of the closest batting average races in baseball history. The sight of the on-deck hitter jumping and yelling with uninhibited joy after an 8 – 4 defeat had to be one of the strangest sights of the 1949 season.

Kell would play 826 games as a Tiger and become one of the most beloved figures in Detroit sports history. After a trade to the Red Sox in 1952, Kell would finish his career with two-year stints in Boston, Chicago, and Baltimore. With the Orioles, in this last season, he became a mentor to a young third baseman with some promise named Brooks Robinson.

Despite the reality that the 34-year-old Kell was playing his last baseball campaign in 1957 and Robinson was just 20-years-old, the two Arkansans would cross paths again. That reunion would be uniquely memorable for the two third basemen and mark a significant milestone in the history of their home state’s baseball legacy.

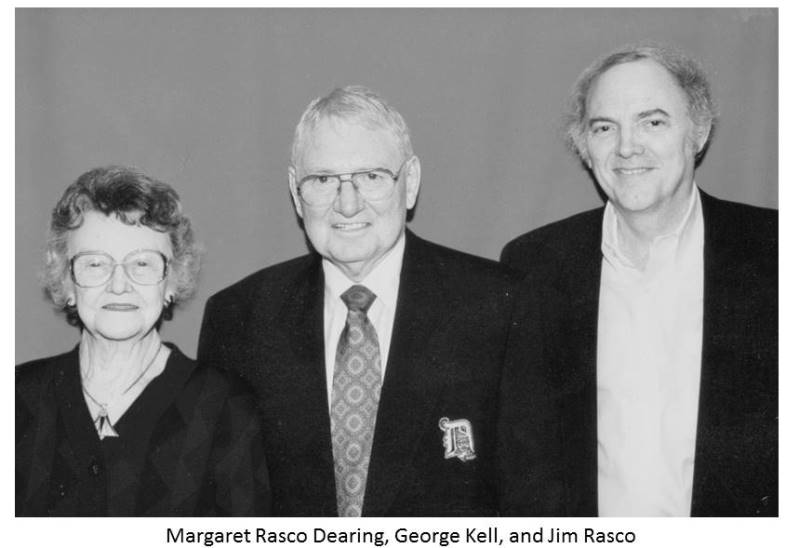

Robinson and Kell would share the stage at the Baseball Hall of Fame induction on July 31, 1983. Both had been previously inducted into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame, and Jim Rasco, official historian of the ASHOF was a special guest of Kell on that occasion. Rasco was not just representing the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame. He was Kell’s unofficial historian and personal friend, a connection made more significant by the coincidence that Rasco’s mother, Margaret Rasco Dearing, was one of George’s high school teachers.

Rasco recalled later that the event was a seminal moment in a half century of baseball history when a rural state like Arkansas produced an inordinate number of major league baseball players. Kell’s and Robinson’s induction marked the only time two Arkansas natives were inducted into baseball’s hall of honor on the same day. The Arkansas historian would describe it as “one of the most memorable events of his lifetime.” In retrospect, the induction marked the end of Arkansas baseball’s golden era.

George Kell continued to be part of the broadcast team of his beloved Detroit Tigers until his retirement in 1996. During those years of his second baseball career, Kell would continue to commute to Detroit from his home in Swifton. George Kell died on March 24, 2009, and is buried in his beloved home town.

“I have always said that George Kell has taken more from this great game of baseball than he can ever give back. And now I know, I am deeper in debt than ever before.” – George Kell at his Hall of Fame induction 1983

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

One response to “George Kell, Swifton’s Hall of Fame Third Baseman”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

I fondly remember when George Kell spoke at the Brinkley Rotary Club many, many years ago. It was Father-and-Son night at the weekly meeting, and my Dad took me with him. I still may have that Rotary Club bulletin which Mr. Kell signed for me.