Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

Smead Jolley played his last professional baseball game more than 80 years ago. Yet in a sport that loves its numbers; his name is still mentioned among the greatest hitters in Arkansas baseball history. Conversely, his detractors can defend a claim that he was one of the worst defensive major leaguers of all time. The late Terry Turner, one of Arkansas’s most respected baseball historians, appropriately christened Jolley, “The Hit and Miss Man.”

Jolley had a lifetime major league batting average of .305 and a career minor league batting average of .369, lofty marks by any standard. In a professional career that included more than 2,400 games in the majors and minors, Jolley hit more than 360 career home runs and had a lifetime batting average of .357 for all professional games.

Smead Powell Jolley was born in Union County, Arkansas, in 1902, and grew up in the small community of Wesson. According to Jolley, he headed out on his own about age 16, and by his late teens, he had found work in the oil fields in nearby El Dorado. The discovery of oil in 1921 had turned El Dorado from a quiet farming town into a bustling boomtown. Jobs were plentiful but difficult. Young Jolley soon decided he would rather play baseball than work at hard labor. “I was a better pitcher than an oil worker,” stated Jolley.

Jolley broke into pro baseball in 1920, as a 20-year-old pitcher, with Greenville in the Cotton States League. He continued to pitch with only moderate success for this first three years in pro baseball but he never failed to post a batting average above .300. It soon became obvious that Jolley’s future was as an everyday player. By 1925, he was a regular outfielder with Corsicana in the Texas Association, where he hit 26 homers and batted .362. At the end of Corsicana’s season, he was sold to the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League.

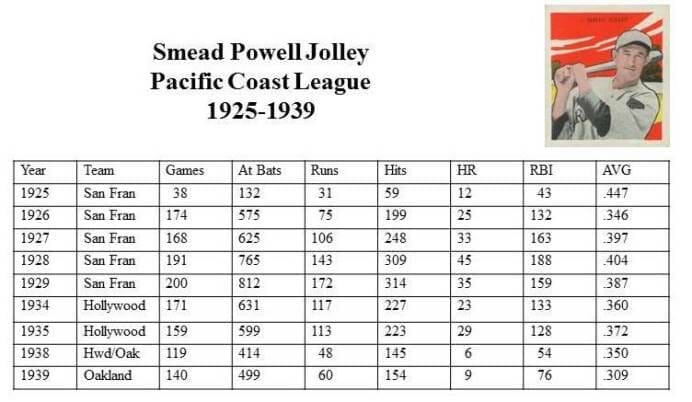

The Pacific Coast League was an attractive place to play. The league was considered a small step below major league quality. Playing in a temperate West Coast climate, the PCL often played schedules of 200+ games from late February into November. Salaries were comparable to the major leagues, and with no competition from the stars of the eastern cities, the players were celebrities.

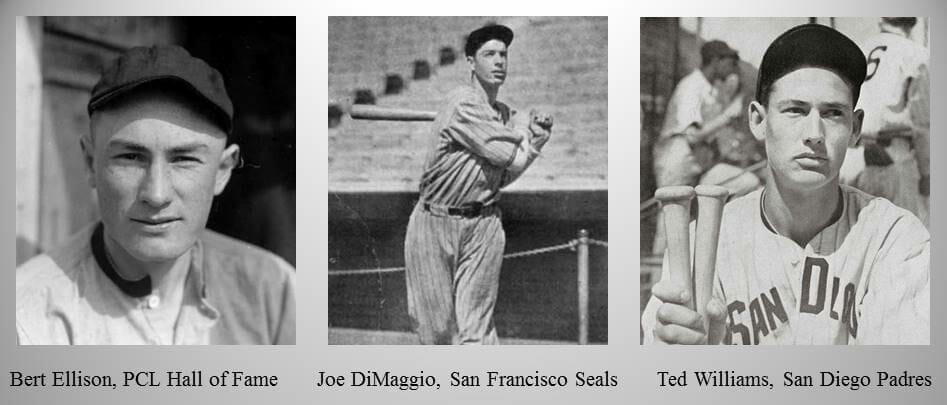

Many Arkansas-born players had their best years in the coast league, and some of baseball’s all-time greats made their pro debut in the PCL. Yell County’s Bert Ellison was inducted into the PCL Hall of Fame in 2006. Joe DiMaggio started his career in Oakland, as a 17-year-old baseball prodigy, and Ted Williams played his first game in 1936 for San Diego in the PCL.

Jolley would play nine seasons in the Pacific Coast League, five in the 1920s, and four seasons in the 1930s, separated by a four-year stint in the major leagues. He hit .388 for the San Francisco Seals during his first five years in the PCL, including a remarkable .404 batting mark in 1928. In 1929, Jolley’s .387 average in 200 games, earned him a trip to the American League Chicago White Sox. He left the PCL with a pre-established reputation as a “hit and miss man.” One California writer described Jolley’s efforts in the outfield as “…like a child chasing bubbles,”

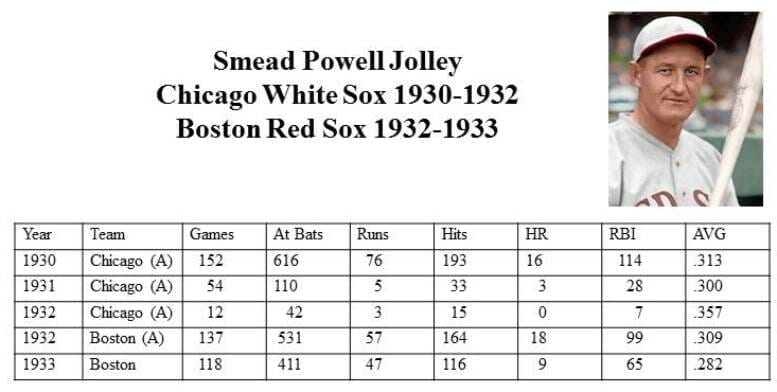

Jolley played in the White Sox outfield for parts of three seasons, batting .314 over his time in Chicago, but failing to distance himself from the prevailing opinion that he was a liability in the field. Traded to Boston in the spring of 1932, he continued to be a consistent .300 hitter and a team leader in runs batted in. His batting marks, examined alone, indicated he would enjoy a long career in the big leagues, but his reputation as a poor outfielder clouded his profile and doomed his major league future.

Smead Jolley was not a good outfielder. Maybe “not a good outfielder” was an understatement to much of the late 1920s baseball community. The unflattering analysis of Jolley’s defensive skills could have also been a convenient exaggeration, unfairly attached to a somewhat limited outfielder, simply because it made a good story. Baseball’s past is filled with colorful stories, and there is no shortage of tales about Smead Jolley’s adventures in the outfield.

One of the most questionable incidents had Jolley patrolling left field for the White Sox in a game at Philadelphia against the As, or some say it was in Cleveland against the Indians. Another possibility is this sadly humiliating event never happened at all but is a combination of plays and embellishments that creates a tale too good to refute. Regardless of its accuracy, the story began when a sharp single was hit Jolley’s way and rolled between his legs as he attempted to field it. He turned to play the ball after it hit the wall, and it rolled back between his legs. By that time, the runner was headed for third. Jolley ran down the ball and threw it into the home dugout. The runner scored, and Jolley had the dubious distinction of making three errors on the same play.

The fact that a box score with three errors charged to Jolley on the same play can’t be found, doesn’t deter the story’s defenders. They simply explain that the official scorer took pity on the befuddled young fellow and only charged him with one error.

Although at almost 6’4” and somewhere near 220 lbs., Jolley was certainly not a gazelle in the outfield. He did, however, lead the league in assists by an outfielder in 1930. He also pulled off an unusual fielding feat typically performed by speedy outfielders, when on May 27, 1930, he recorded an unassisted double play while playing right field. Despite this evidence in his favor, Jolley was subjectively branded by managers as a poor fielder, capable of costing his team more runs than his good hitting could produce.

With Boston in 1933, Jolley saw his playing time significantly reduced. He played in 118 games and had over 160 fewer at-bats. His home run total plummeted to nine and his RBIs fell from 99 to 65. Boston was giving up on him, and the pervasive idea that Jolley cost a team more runs with bad defense than he produced at-bat had now become widely accepted.

Smead Jolley Hollywood Stars

Joe E. Brown and Olivia De Havilland in Alibi Ike

December found Jolley part of a multi-team trade that ended with him being sold to Hollywood in the Pacific Coast League, where he picked up right where he left the PCL. Jolley hit .360 with 23 homers in 1934 and .372 with 29 home runs in 1935. The big country boy the fans knew as Smudge was a popular player for the Hollywood Stars, and his hillbilly charm made him something of a celebrity in a city of celebrities. Jolley even got a bit part in the baseball movie, Alibi Ike, with Joe E. Brown and Olivia De Havilland.

Smead Jolley would play seven more minor league seasons after his demotion from the major leagues. Most of those games would be played in his adopted baseball home in the Pacific Coast League. His batting average was above .300 in each of the seven summers in the twilight of his career.

Smead Powell Jolley was a phenomenal hitter. Perhaps he was one of the greatest hitters of all time and certainly one of the premier sluggers of his era. Although his name will never be found among the baseball greats enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame., he was elected to the PCL Hall of Fame in 2003 and the Union County, Arkansas, Hall of Fame in 2013.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Jim Yeager

In 1942, the Americans Tom Brokaw would later celebrate as our...

In 1920, the winter days between Christmas and New Year’s Day promised...

The 1951 baseball season arrived in Little Rock with little cause for...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment