Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

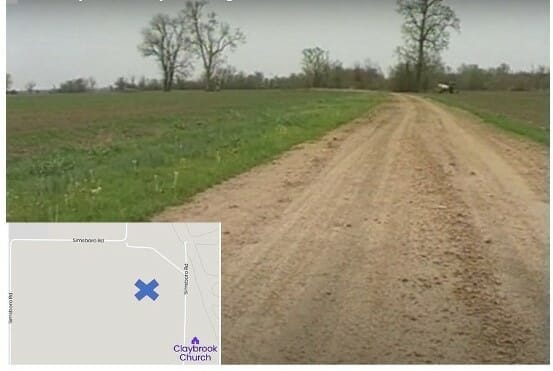

Down a dusty Arkansas Delta road that only farmers travel, and just past the unmarked location of a long-abandoned town, today’s travelers unknowingly pass the site of a historic baseball park that disappeared years ago.

Thousands of fans once made the excursion from the larger cities by train or came from local farming villages to see the Claybrook Tigers play. Their opponents came from cities like Little Rock and Memphis, and from as far away as Cuba.

Location of the lost town of Claybrook, in Crittenden County, Arkansas

There is no historical marker on Simsboro Road, about 10 miles northeast of Hughes, Arkansas, although some of the most noteworthy minor league baseball games in our state’s history were played there. Today, only the legend of the Claybrook Tigers remains.

The community, once called Topaz, was renamed Claybrook after the African-American entrepreneur who transformed a cotton field into a thriving timber business, hiring dozens of locals, and entertaining the society crowd from Memphis on weekends. In its heyday, the boomtown of Claybrook, Arkansas, featured a boarding house, a sawmill, a general store, a dance hall, and a championship-level professional baseball team.

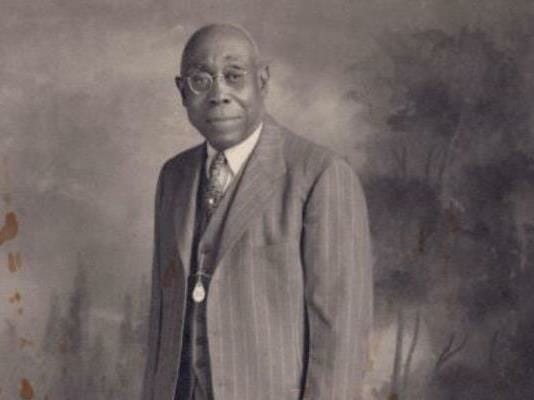

John C. Claybrook

John C. Claybrook arrived in Crittenden County, Arkansas, about 1905. He was in his early 30s, and although he had little formal education, he was destined to become one of the most respected businessmen of his time. Shrewd and determined, Claybrook reportedly could not read nor write, but he could do business calculations in his head faster than his associates could calculate the transaction.

Upon his arrival in the Delta, Claybrook saw other farmers clearing native timber to make room for cotton. Claybrook had an idea. In addition to his modest farming operation, he would contract for the removal of the virgin cypress, oak, and hickory and process it into lumber at his sawmill. His lumber business thrived, and by the early 1930s, his original two-acre farm had grown to more than 1,200 acres. John Claybrook had become one of the wealthiest and most respected Black businessmen in the region, but his affection for the hard work it took to reach that status was not easily passed on to his family.

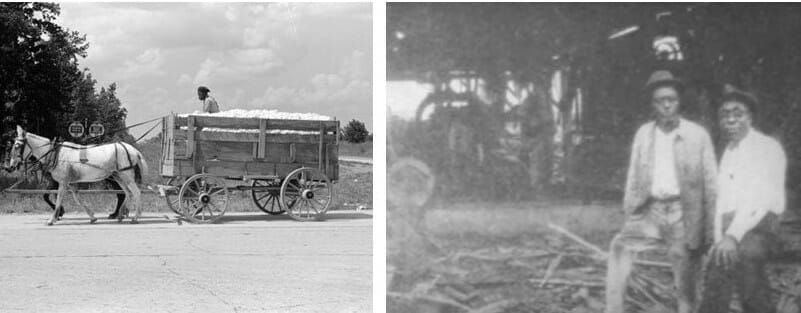

(Left) Crittenden County cotton on the way to the gin. (Right) John Claybrook at his sawmill circa 1930.

Claybrook’s daughter, who left the farm to become a schoolteacher in Memphis, recalled that life on the plantation came with a demanding schedule. Weekends were often spent entertaining the Memphis and Little Rock society crowd that had arrived by train for a good time. Monday morning began at sunrise back at the sawmill or the cotton field and continued until darkness ended the workday. The routine was part of the philosophy the elder Claybrook lived by, but it was a difficult lifestyle for his children. The least satisfied of his family was his teenage son.

John Claybrook Jr was born in 1916, but despite growing up in a somewhat privileged home, plantation life was not for him. Young John loved sports, and his father hoped that sponsoring a local baseball team might keep his son down on the farm. That team would become the Claybrook Tigers. While town teams were the norm in the South in those days, an obscure sawmill town with a professional team good enough to challenge the best baseball teams in the region was a historic exception.

An association that offered regulated professional baseball opportunities to men of color had been created in 1920 and became known as the Negro Leagues. The young men drawn to the newly created teams had big-league skills, but before the formation of the new organization, they were restricted to barnstorming against local town teams. The Claybrook Tigers played in the Negro Leagues’ somewhat informal minor leagues. These leagues seldom played a standard regular-season schedule, but often met in a post-season championship series.

Tigers vs. Cuban All-Stars

Newspaper photograph of Claybrook Park

According to the Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia, the Tigers began with a modest schedule in 1932, and as the quality of players John Claybrook recruited improved, the team challenged the best teams the Negro Leagues had to offer. Claybrook built an impressive ballpark for his team and began to recruit some of the top Black baseball players in the South. By 1935, he had put together a championship-level team.

He did not have to look far to find some of his top players. Switch hitter Alfred “Greyhound” Saylor was from Blytheville, Arkansas, and ace pitcher Theolic, “Fireball” Smith was born in Wabbaseka. The Tigers’ first baseman Bill “Wing” Ball grew up in Little Rock. Ball had no lower right arm but was an excellent defensive first baseman and a local favorite.

In September 1935, the Claybrook Tigers defeated the Memphis Red Sox four games to three in playoff series to claim the 1935 Negro Southern League title. The Memphis Commercial Appeal gave the championship series about 50 words on page 11. The story, under the small headline, “Claybrook is Crowned,” noted that Theolic Smith struck out eight in the 5–2 win.

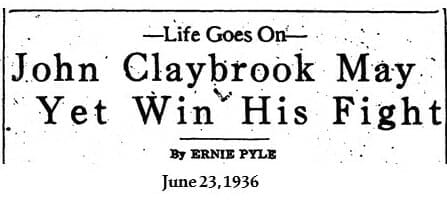

Legendary newspaper columnist visits Claybrook, Arkansas

Ernie Pyle

Despite the 1935 post-season success, there were some troublesome issues in Claybrook. If the number one goal of John Claybrook Sr. was to entertain his son that part of the plan was in danger.

In the spring of 1936, nationally-known newspaper columnist Ernie Pyle made a trip to Claybrook. Pyle, who would later lose his life covering World War II, was traveling the country writing a syndicated column called “Life Goes On.” In his column about his visit with John Claybrook Sr., Pyle noted the importance of the father’s plan to use the baseball team to keep his son in the Delta. Pyle gave hope that John Sr. would get his wish, but the restless young man would soon leave the farm life behind.

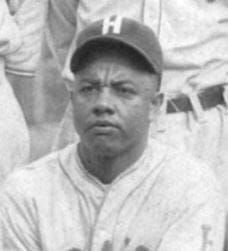

Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe

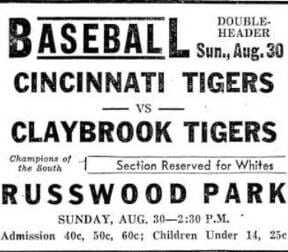

Gameday at Russwood Park

John Claybrook Sr. decided to make an aggressive change in the Tigers based on the 1935 success. He brought in a big-name player-manager called “Double Duty” Radcliffe. Theodore Roosevelt Radcliffe earned his nickname by regularly pitching one game of a doubleheader and catching the next. As part of Radcliffe’s deal to come to Claybrook, he lived with the Claybrook family and received a large share of the gate receipts.

The team’s success and the extra expense of Double Duty’s paycheck led to more games in Memphis at the more spacious Russwood Park. In order to increase revenue, the Tigers played most of their big-name opponents in Memphis in 1936, with less than six games actually played in Claybrook.

By the end of the 1936 campaign, Radcliffe and Claybrook were at odds over Double Duty’s share of the gate, and a disappointed father realized that his son was never going to be satisfied in the Arkansas Delta. There is no record that the Claybrook Tigers played after 1936. Radcliffe left for Cincinnati with most of the better players, and John Claybrook Jr. moved on to the city life he preferred. By the early 1940s, John C. Claybrook had sold his Arkansas operation and moved to his alternate home in Memphis. He passed away in 1951.

The 1935 Claybrook Tigers were champions of a league known as the Negro Southern League. Fifteen years prior to the Tigers’ title, the Little Rock Travelers won a pennant in a segregated minor league called the Southern Association. The 1920 Travs are the subject of dozens of feature stories, but the history of the Claybrook Tigers was generally forgotten until two Arkansas historians set about to honor the team’s accomplishments.

Caleb Hardwick’s work in the Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia contains the most complete research available on the Negro League Era’s history in Arkansas. Among the teams, leagues, and ballparks included in the online publication is a look back at the Claybrook Tigers.

In 2001, David D. Dawson of the University of Arkansas produced a documentary on the Claybrook Tigers called Swingin’ Timber. Dawson drew from extensive research and the photo collection of Dr. John R. Haddock of the University of Memphis to create the definitive tribute to one of the most important teams in Arkansas baseball history. Watch Swingin’ Timber courtesy of Dave Dawson.

Claybrook photos courtesy of David Dawson, the John R. Haddock Collection, and the Arkansas Baseball Encyclopedia.

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

One response to “The Legend of the Claybrook Tigers”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

Jim, I sure do love it when you share a new story!