Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

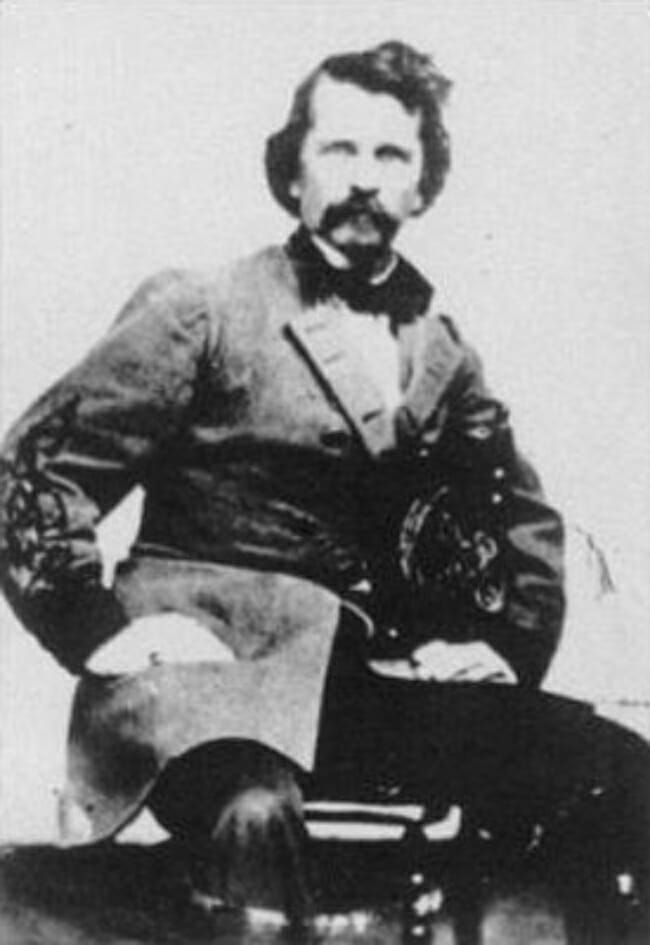

Many people played a part in creating Arkansas as we know it today. Some of those names are well known, but others hide in obscurity. Aaron “Rock” Van Winkle is one of those names. Van Winkle occupied an interesting position in Arkansas history as first a slave and then a freedman. His presence in Northwest Arkansas was well-known and respected, and he shouldered immense responsibility in the timber industry as the state developed through the late 1800s.

A Man With Two Names

Aaron Van Winkle was born under a different name: Aaron Anderson. It was common for slaves to be given the last names of their owners, and Aaron Anderson was named for his owner, Hugh Anderson. Aaron was born in 1829 and arrived in Arkansas as a child, where he lived on Hugh Anderson’s farm in Benton County. Here, Aaron and 13 other slaves worked hundreds of acres. Hugh Anderson was a land appraiser and surveyor, which made him familiar with land across Northwest Arkansas. He bought hundreds of acres in both Benton and Washington County.

While Aaron Anderson was growing up in slavery in Arkansas, another Northwest Arkansas pioneer was forging his own fortune literally adjacent to Anderson’s farm. Peter Van Winkle grew up in Illinois after his family arrived from New York, seeking a new life on the frontier. Van Winkle came to Arkansas around the same time as Anderson. He established an 80-acre homestead near Fayetteville. He and his wife, Temperance, eventually raised 12 children. Van Winkle was known as a “sod buster” and likely helped plow much of the farmland in the area. In 1850, the family moved to Benton County with an eye towards developing the timber industry in the prime forestland in the area.

There is no record of when Aaron Anderson became the property of Van Winkle, but it was likely after Hugh Anderson’s death in 1849. Aaron was around 21 years old at the time his ownership passed from Anderson to Van Winkle. He joined Van Winkle on his Benton County land just as Van Winkle was at the beginning of establishing his sawmill. Peter Van Winkle wasn’t the first to establish a timber mill in the area. That credit goes to Sylvanus Blackburn, who established both a gristmill and a sawmill at War Eagle.

Though not from Van Winkle Mill, this equipment is similar to what the Van Winkles would have used in their mill in the 1800s. Photo: Historic American Buildings Survey Nathaniel R. Ewan, Photographer January 6, 1939. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

Van Winkle partnered with Blackburn instead of competing directly with the already successful mill. He built his own mill in a hollow in eastern Benton County, named Van Winkle Mill, and steadily grew his timber business. Aaron, by now known as Aaron Van Winkle, was an integral part of Van Winkle’s business. He became skilled at every aspect of the work and earned both his nickname, “Rock,” and the title of engineer. This didn’t denote Aaron Van Winkle’s level of education. In fact, he never learned to read, as most slaves were not allowed schooling. Instead, it referred to his deep knowledge and skill in the lumber industry.

From Slave to Freedman

Rock Van Winkle became a well-known figure in Northwest Arkansas and the surrounding areas. Demand for timber for building homes and businesses had increased. By the time the Civil War began in 1861, Van Winkle Hollow held a steam-powered sawmill, a gristmill, a blacksmith shop and other shops, Van Winkle’s own large home and Aaron’s home, along with other slaves who likely lived at the southern end of Van Winkle Hollow. Rock Van Winkle worked alongside the other slaves, which numbered at least six in 1856.

Van Winkle Hollow was located on a well-maintained road (likely maintained by Van Winkle and Blackburn’s employees and slaves). In its day, the mill was an important stop and received regular travelers who brought news with them, especially of the “Border Wars” between pro-slavery supporters in Missouri and abolitionists in Kansas. Rock Van Winkle was likely well-informed about what was happening just north of Arkansas. In 1861, Arkansas seceded from the Union and joined the Confederate States. Van Winkle Mill continued to operate and supplied the lumber for the Confederate camp located about 8 miles west of Van Winkle Hollow. Camp Benjamin was completed in February 1862, but its existence was fleeting. With the Union Army pushing into Arkansas, the Confederates burned the new camp rather than turn it over to the Union.

The Battle of Pea Ridge occurred just weeks later, ending in defeat and retreat for the Confederate Army. Although the actual battle was 20 miles from Van Winkle Hollow, the area would have been central to troop movements, and just down the road from the popular Elkhorn Tavern, an important stop on the Butterfield Trail where travelers could get a meal, rest, mail letters, and get the news. During the Confederate retreat, the ranking general, Earl Van Dorn, stopped at Van Winkle Hollow. Union troops would also have traversed the area, making life uneasy for those in the hollow. In early 1863, Van Winkle’s partner, Sylvanus Blackburn, was killed by Union supporters at War Eagle Mill.

It was in this atmosphere that Peter Van Winkle decided to flee the war, either in late 1862 or early 1863. The Van Winkle family, including Rock, and the other slaves, all fled to Texas. The mill was burned to the ground shortly after the Van Winkles left. The family and its slaves survived the war and returned from Texas in 1866. Rock returned with the group, now a freedman.

Though Rock continued to work for Peter Van Winkle, life was different now. For one, he was able to marry and wed Jane, another of Van Winkle’s former slaves. The couple already had one child together with another on the way. They would eventually have 10 children. Rock was now a paid worker, but he continued in his work for Peter Van Winkle, helping rebuild the sawmill, grist mill, and everything else that had burned down. Rock also built a new home for his growing family.

A Prosperous Legacy

While rebuilding the mill and shops in Van Winkle’s Hollow wasn’t easy, it turned out to be a prosperous decision. Van Winkle’s sawmill supplied timber to nearly every town for miles in either direction. Rock Van Winkle was a trusted employee and oversaw much of the transportation of wood to various sites, including the University of Arkansas. Jane worked in Peter Van Winkle’s home. Together, the couple also tended chickens, pigs and a few cattle. By 1880, they had saved enough money to buy their own land.

The family bought an 80-acre plot near present-day Johnson, Arkansas. By this time Peter Van Winkle had moved his family to Fayetteville. The land increased Rock’s prosperity, especially its prime location to a future railroad line. In 1882, Peter Van Winkle died suddenly. Van Winkle’s wife, Temperance, kept Rock on as an adviser and paid him a dollar a day, which was twice as much as some of the mill workers. In 1884, Rock bought 80 acres in Benton County after selling his land in Johnson. Peter Van Winkle’s son-in-law, J.A.C. Blackburn had acquired Van Winkle Hollow. He closed the mill in 1890. By this time, Rock was already farming his own land, milling it, and working in monuments, supplying gravestones to local cemeteries.

Aaron “Rock” Van Winkle continued to be a well-known figure in the area. He was one of just over 100 Black residents in Benton County, but his travels delivering lumber had taken him across the region and into other states as well. When he died in 1904, his funeral was large and well-attended, and J.A.C. Blackburn gave the eulogy, saying “He was one of the best men I have ever known.” Although Rock Van Winkle lived in a time where he endured slavery before being allowed to build his own family and wealth, he did play a large role in building Northwest Arkansas, as nearly every town had the touch of Van Winkle’s timber. Aaron Van Winkle’s grave is in Bentonville Cemetery, where it stands as a reminder of Rock’s life and influence in Arkansas history.

Explore Van Winkle Hollow in Hobbs State Park, where you can walk around the grounds where Aaron Van Winkle lived and worked, and learn more about the sawmill and the Van Winkles in Arkansas.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Kimberly Mitchell

The XXV Winter Olympics concluded this February in Italy, and one of the...

Scott Fitzgerald never forgot the feeling of freedom he got from biking...

Trains revolutionized the United States in the 1800s. People and goods...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment