Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

There was once a time when the state of Arkansas was nearly synonymous with The Arkansas Traveler. This turn of phrase has represented the state in many ways, from a lively tune to a more negative view of Arkansas. Through three centuries, the term has survived and taken on new meanings. Is the Arkansas Traveler a person, a song, a sports team or a visitor to the state? Travel through the history of The Arkansas Traveler and decide for yourself.

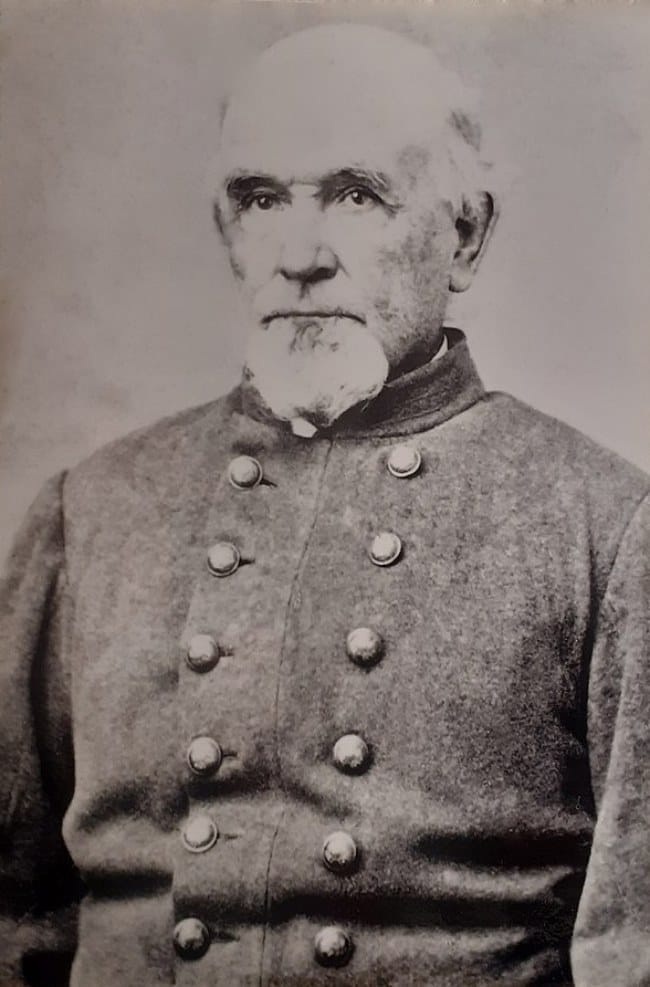

The Arkansas Traveler traces back to one Kentuckian turned Arkansan and a story. Sandford “Sandy” Faulkner was born in Kentucky in 1803. His father ran a tavern until they moved to Arkansas in 1829. Sandy Faulkner moved with his parents and extended family. The Faulkner family ran two cotton plantations in Chicot County, and Sandy managed them. At the same time, he served in the Second Brigade of the Arkansas Militia.

Faulkner was aide-de-camp to the commanding officer. As aide-de-camp, Faulkner managed communications for his senior officer, relayed orders and acted as a secretary or personal assistant. During this period, serving in the Territorial Militia and after statehood, the Arkansas Militia, was often a stepping stone for men interested in politics. Faulkner had several runs at Arkansas political positions, from the territorial council in the 1830s to two failed attempts for the Arkansas legislature in the 1850s. Although he was never elected, Faulkner knew the right people, and the state was young and needed leaders.

In 1838, Faulkner was appointed a commissioner of Chicot County and the President of the Columbia branch of the Real Estate Bank of Arkansas. This would be his financial downfall when the banks failed in 1843. Still, in the short period between his appointments and financial failure, Faulkner ran in political circles, which is what led to his story about the Arkansas Traveler.

Faulkner and other politicians were stumping across the state in 1840 as the presidential election between Martin Van Buren and William Henry Harrison loomed. The story has Faulkner traveling in the company of Archibald Yell (Arkansas’s second governor), Ambrose Sevier (a member of “The Family” and a U.S. Senator from Arkansas), William Fulton (Arkansas’s last territorial governor) and Chester Ashley (also a U.S. Senator and member of “The Family”). The men were traveling outside familiar territory, either in Yell County or the Boston Mountains. Though the exact location has been lost to time, it’s certainly conceivable that the statesmen were lost in the deep depths of the Ouachita National Forest or the rugged, forested hills of the Boston Mountains. Either way, Faulkner starts his tale with the fact that he was lost and stopped at a cabin to ask for directions.

This is where history meets myth. Faulkner told this tale many times over the next several decades, and in it, he only mentions the Arkansas Traveler (himself) and the Squatter. A squatter lived on the land but likely didn’t own it. The Squatter was playing a fiddle, and night was falling. In some sources, the Traveler followed the sound of the fiddle to the cabin. What happens next is a dialogue turned into a story and song for the next two centuries. The Traveler called out, “Hallo stranger,” to which the Squatter replied, “Hallo yourself.”

The men begin to banter back and forth as Faulkner angles to stay the night and the Squatter refuses. Meanwhile, he continues to play the fiddle, apparently having trouble with the tune. Finally, the Traveler offers to play the “turn of the tune,” or the second half of the piece (Faulkner was a fiddle player, after all). The Squatter allows him to, and the Traveler plays the tune that became famous, known as the Arkansas Traveler, and played over and over. This story, which Faulkner recited, plays on a well-known oral story-telling tradition of humorous questions and answers, each growing more outrageous. The Squatter is finally convinced to allow the Traveler to stay the night when he plays that tune on the fiddle.

This story took on a life of its own as that famous tune was played across the country. Although Sandford is sometimes credited for the song that accompanies the story of the Arkansas Traveler, other musicians were certainly playing it by the end of the decade. In Buffalo, New York, jazz musician Mose Case performed the tune, officially publishing the song in 1863. A musical composer, W.C. Peters, took credit for arranging the musical score of the Arkansas Traveler, titled “The Arkansas Traveler and the Rackinsac Waltz,” and released in 1847.

Arkansas artist Edward Payson Washbourne painted his version of the Arkansas Traveler in 1856. The painting was reproduced using lithography to print the painting with an initial run of 1,500 paintings. These became so popular that Washbourne became well-known as an artist and would likely have continued his success. Unfortunately, he died suddenly from an illness in Little Rock in 1860. He had an unfinished painting called “The Turn of the Tune” that was later finished by another artist.

The popularity of the Arkansas Traveler continued to spread as a song, a story, and a painting. Currier and Ives, a famous New York-based printing company, printed the Arkansas Traveler in 1870, which proved quite popular. Another art form was quickly growing as well. Vaudeville shows hit their peak between the 1880s and the 1920s. Vaudeville theater presented a series of live acts on stage. Shows traveled around the country, and the Arkansas Traveler became a popular story because of its humorous dialogue and accompanying tune on the fiddle.

Not everyone was pleased with the popularity of the Arkansas Traveler, though. The story emphasized the hillbilly stereotype of the Squatter, lending credit to the long-held opinion of Arkansas as a rural, uneducated state. However, that opinion began to shift when two Arkansans, Chet Lauck and Norris Goff, created their radio show “Lum and Abner” off the hillbilly image Arkansas held. The show began in 1931 and ran for over 20 years. While not directly associated with the Arkansas Traveler story, Lum and Abner embraced the hillbilly stereotype and created acceptance around it. This also created more acceptance of the stereotypes that had developed around the Arkansas Traveler story.

In 1941, the Arkansas General Assembly created the Arkansas Traveler Certificate to give to visitors to the state, especially to honor visitors like President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who received the first Arkansas Traveler certificate on his visit to Arkansas that year. The honorary title of Arkansas Traveler has also been given to Roy Rogers, Maya Angelou, Bob Hope and many other visitors, who each received the title and promised to be goodwill ambassadors to the state.

The name Arkansas Traveler has also been used within sports, beginning with the Travelers baseball team. The team began play in 1895 and has continued using the name through five different leagues. Though the team was first associated with Little Rock, it shifted to the current Arkansas Travelers moniker in 1957. Hazel Walker named her women’s professional basketball team the Arkansas Travelers in 1949. Walker’s Arkansas Travelers truly traveled. They crisscrossed the country, playing only men’s basketball teams and winning most of their games. The Arkansas Travelers played until 1965.

The tune of the Arkansas Traveler was officially recognized as the historical state song in 1987, nearly 150 years after Faulkner introduced the story and tune. The song remains a favorite among folk music fans and fiddle players today.

Listen to a recording of The Arkansas Traveler in a vaudeville show from 1929 at the Library of Congress or a recording of the song performed in 1967 on the fiddle by Henry Reed.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Kimberly Mitchell

The XXV Winter Olympics concluded this February in Italy, and one of the...

Scott Fitzgerald never forgot the feeling of freedom he got from biking...

Trains revolutionized the United States in the 1800s. People and goods...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment