Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

Arkansas is classified as a humid subtropical climate, though you don’t have to tell Arkansans how humid the state is. Its position near the Gulf of Mexico but adjacent to the plains means Arkansas experiences interesting weather year-round. While a humid subtropical climate indicates hot summers, plenty of humidity and generally milder winters, a look at the history of Arkansas weather events reveals a more nuanced climate that brings tornadoes, snow, ice, floods and heatwaves to the state. Look back at some of the most intense weather events in Arkansas, and expect to see more wild weather in Arkansas’s future.

The Sneed Tornado

In 1971, T. Theodore Fujita from the University of Chicago and Thomas Pearson, head of the National Severe Storms Forecast Center, created the Fujita Scale. The scale standardized the classification of tornadoes from F0, for light damage, to F5, for severe damage. Then they looked back at past tornadoes to classify them according to the new system. They found one tornado that hit Arkansas to have caused enough damage to be an F5.

April 10, 1929, was a bad day in Arkansas. Stormy weather spawned several tornadoes over Northeast Arkansas. The tornado formed in Independence County, 3 miles south of Batesville. Its path took it across Jackson County north of Centerville before it reached the communities of Pleasant Valley, also called Possum Trot, and Sneed. Here the tornado hit in full force, with eyewitnesses putting the tornado at half a mile wide. It left homes in splinters, destroyed the Pleasant Valley school and swept bare the landscape.

Survivors said it was difficult to discern from the debris what structure had existed, so thorough was the destruction. The storm killed 23 people and injured another 59, some severely. It affected 75 families in the area, with many losing homes, barns and livestock. An engineer from the Missouri Pacific saved lives that day by managing to outrun the tornado. He pushed the passenger train traveling from Little Rock to speeds up to 75 miles per hour to escape the path of the storm. Several other tornadoes hit that day, with two F4s hitting Izard and Cross counties. All in all, it was a terrible day, and the Sneed tornado still holds the record, and hopefully always will, as the strongest tornado to hit the state.

New Madrid Earthquakes

On Dec. 16, 1811, the earth trembled all along the New Madrid fault line, which runs from Poinsett County northeast through Arkansas, Missouri, Tennessee and Illinois. Residents of New Madrid, Missouri, were awakened by the shaking at 2:15 a.m. The earthquake continued, with a large one hitting about 7:15 a.m. The epicenter for this earthquake was about 3 miles beneath present-day Blytheville, Arkansas. The earthquake changed the landscape along the Mississippi and St. Francis Rivers. The Mississippi River ran backward when parts of the riverbank collapsed and blocked the river for a period of time. Land in parts of Craighead, Mississippi and Poinsett counties sunk as the earthquake opened fissures in the ground. Previously arable land became swamped with water. Today, the St. Francis Sunken Lands Wildlife Management Area still exhibits the effects of the earthquake.

The earthquakes continued that winter, driving away many settlers, changing the landscape, and killing an unknown number of people. From Jan. 23 to Feb. 4, 1812, some 2,000 earthquakes struck the region, with aftershocks continuing into April. The tremors stunted settlement in Northeast Arkansas and affected countless Native American tribes in the area. The true number of deaths is unknown, although the number of deaths on land was reported to be around 100 people. This doesn’t account for those affected by the earthquakes while traveling the rivers on steamboats, and any deaths experienced in Native American communities.

Arkansas still experiences small earthquakes along this fault line every year, and the possibility of another large earthquake still exists.

The Ohio-Mississippi Valley Flood of 1937

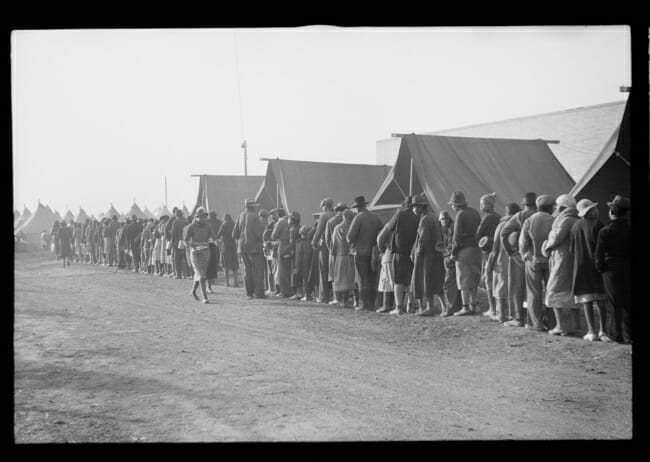

Ten years after the Great Flood of 1927, Arkansas experienced another devastating flood. Previous floods in 1915 and 1927 had convinced the country of the need for flood control, but the levee systems and spillways still couldn’t handle the estimated 165 billion tons of water that poured into 11 states in the Ohio-Mississippi River Valley, including Arkansas. In January of 1937, Arkansas received over 12.5 inches of rain. Heavy rain swelled the Mississippi, White and Arkansas Rivers and caused massive flooding in southeastern Arkansas and particularly affected agricultural lands and farming families. Over 1,037,500 acres of agricultural land and 756,800 acres of other land flooded, driving sharecroppers and farming families away from their homes. Over 40,000 families were affected.

The American Red Cross cared for 17,743 families in temporary refugee camps. Other families fled across the border to Tennessee. Schools, fairgrounds and churches temporarily housed families, handed out meals and provided medical services. Field hospitals also tended to patients affected by the floods and dealt with cases of flu, pneumonia and took the opportunity to vaccinate refugees against typhoid and diphtheria. Many families were able to return to their land by late March, but the economic toll was high, with the cost of rebuilding and replacing household goods at $12.5 million.

Although Arkansas was less affected economically than other states, both the death toll and injury rate were higher than any other state with 33 recorded deaths and 322 people injured. This winter flood followed on the heels of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl and caused great suffering in Arkansas. Beginning in the 1940s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built a series of dams across the state to ensure this level of flooding wouldn’t affect Arkansas again.

The 2009 Ice Storm

Arkansas is no stranger to ice storms, as its position as a subtropic climate often means winter weather falls as ice or sleet rather than snow. On Jan. 26, 2009, a large storm system moved from the Rocky Mountains across the plains and into Arkansas, where the air temperature was already hovering just below freezing in the northern half of the state. Freezing rain began to fall and continued through Jan. 27, coating much of the area in one to two inches of ice. As precipitation continued, much of northern Arkansas received one to 2 inches of snow on top of the ice. Trees and power lines both snapped under the accumulated weight, and over 350,000 people lost power as the storm moved through.

The process of restoring power was complicated by the loss of 30,000 utility poles downed by the ice. It took nearly a month to restore power to all customers. The ice storm killed 18 people across the state. Arkansans experienced the phenomenon of thundersnow, or thunder ice, during this storm as well. This ice storm caused over $80 million in damages across the state and lands at the No. 3 spot on The Weather Channel’s list of top 10 most damaging ice storms in history.

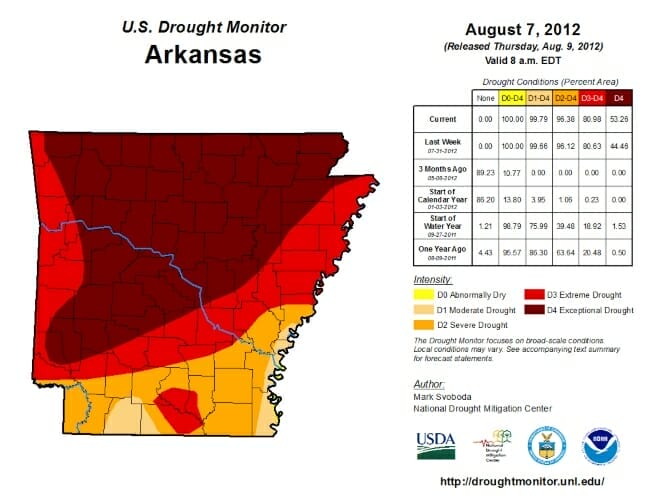

The Drought of 2012

As part of the humid subtropical climate, Arkansas usually experiences a good amount of rainfall, particularly in the spring, which supports widespread agriculture in the state. In 2012, however, the state faced the worst drought on record. From April to July, rainfall was six to 12 inches less than normal statewide, with rainfall falling 30 to 60%. Fayetteville was 12 inches below normal at July’s end, with Little Rock down 10.5 inches and Jonesboro almost 11.5 inches below normal rainfall. Searcy County recorded no rainfall in May. Much of Western Arkansas experienced the driest May on record, and June brought intense heat that only worsened into July.

Many cities recorded a record number of days over 100 degrees and some with days over 105. Among them, Russellville experienced 30 days over 100, with 14 of those days over 105. The hottest day topped out at 109. Little Rock, Hot Springs, Fort Smith and Mountain Home all also experienced record-setting days of 100-degree heat, with over 20 days of scorching temperatures in each city. By Aug. 8, 2012, 72 of Arkansas’s 75 counties had been declared disaster areas. Nationwide, 33 states were affected by the drought.

Arkansas farmers endured a difficult summer that saw small yields of hay. At the same time, they struggled to feed animals and much livestock had to be sold as hay prices rose. Area rivers, lakes and streams also had record low levels of water, and fire danger increased. Area 4th of July fireworks shows were canceled. As the state moved into fall and winter, some rainfall began to ease drought conditions, and 2013 brought record rainfall amounts to end the drought.

Throughout Arkansas state history, the weather has continued to be unpredictable, and if Arkansans can count on anything, it’s that the unpredictability of the weather in Arkansas will continue to challenge its residents.

Cover photo of flooded homes in Forrest City, Arkansas courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

One response to “Historic Weather Events in Arkansas”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

[…] Preparedness Month in Arkansas Historic Weather Events in Arkansas Experience a Tornado at the Museum of […]