Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

Arkansas is known for many things, from our beautiful mountains and lakes to our unique diamond mine, or even calling the Hogs. Still, many wouldn’t equate Arkansas as the home to the most species of freshwater mollusks in the world. With 83 species of these shelled animals in rivers and lakes across the state, Arkansas hosts the most freshwater mussel species west of the Mississippi, but many of them are endangered. The history of the mussel in Arkansas is to blame for much of the current situation, and the future of the freshwater, shelled animals is uncertain.

Mollusks, Not Fish

Mussels are interesting creatures. They’re not fish. They can be called freshwater clams since they are from the same family, the bivalve mollusk. They have two shells that hinge together and protect the mussel, which is a soft-bodied invertebrate that lives its entire life in the same shell. Also, they only have one foot, which they use to slowly move along a river bottom or lake bed. And they breathe and eat through their gills, which continuously pump water through the mussels. Like fish, they take in oxygen this way, but they also ingest food particles that pass through the gills. Mussels thrive on algae, bacteria, and other microscopic, organic matter. Inedible material that passes through their gills falls to the river or lake bed and becomes sediment.

Mussels are filter feeders and inhabit an important role in the ecosystem of our Arkansas lakes and rivers. They are extremely sensitive to pollution since they filter everything through their gills. They also cannot survive in water filled with heavy sediment, or water that is too deep, cold and still. For this reason, you’re more likely to find them in riverbeds instead of lakes and ponds, though some species have adapted to survive in deeper water. In Arkansas, mussels live in nearly every river, though they’re easily missed among the rocks.

Mussel Reproduction

Mussels have an unusual reproduction cycle. They rely on a host fish to incubate their eggs. Certain species of mussels only use a specific fish as a host. If that fish isn’t abundant, then mussels struggle to reproduce. Male mussels release sperm into the water, relying on the currents to carry it to the female mussels. Once eggs are fertilized, females use a variety of methods to attract the preferred host fish. Some release their larvae into the water to allow them to swim to the host and attach to the fish’s gills or fins. Other mussels actually use a lure, a piece of tissue that mimics a small fish, that draws the host fish to it. When it grabs the lure, the mussel takes the opportunity to inject the larvae into the fish. The larvae cause no harm to the fish.

Once they’ve grown enough to become juvenile mussels, they detach from the fish and drop to the waterbed. If the bed is suitable, juveniles create a new mussel bed. They begin to secrete minerals that harden into shells. Mussels continue to add layers to this shell their entire lives.

Arkansas Pearl Rush

Mussel shells aren’t just used to protect the creature inside. When sand or an irritant enters the shell through water siphoning, the mussel begins to layer the irritant in the same proteins as its shell. Over time, this develops into a pearl. Freshwater pearls play an interesting role in Arkansas history. Pearls have been found in Native American burial sites. Arkansas was known for its freshwater pearls long before the area became a state. A pearl rush began in the 1800s that trickled down from the Ohio River Valley into Arkansas. The White River became especially well known for its quantity of pearl-containing mussels. Northeast Arkansas became famous and people rushed to harvest pearls.

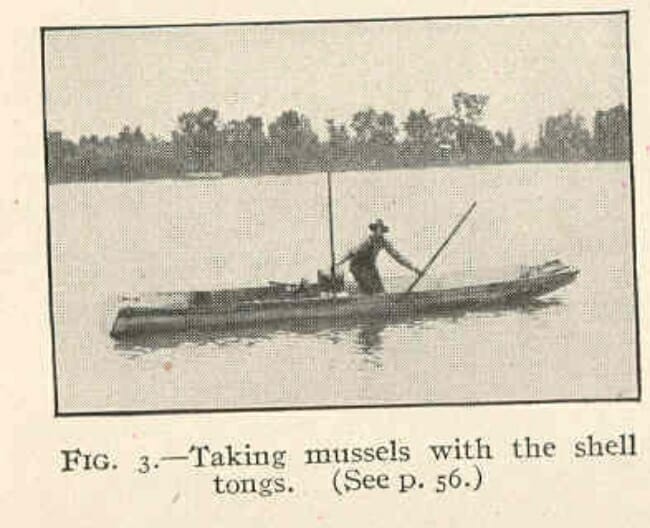

At first, people could simply wade into the water and harvest the mussels from shallow riverbeds. Once these mussel beds had been ravaged, the hunters had to search deeper waters. They used pearling rakes, which were long-handled tongs, to reach mussels in deeper water. The first pearl rush in Arkansas happened from 1897 to 1903. People set up tents along the rivers for quick access. Some people left farms and stores unattended to join in the rush. By 1905, the rush had ended because the riverbeds had been so harvested. Though the pearls were mostly gone, some entrepreneurs realized the insides of the shells made beautiful buttons. Soon, a new industry was born. The pearl interiors were shipped to button factories in the Northeast, where they were made into pearl buttons and shipped around the world.

Plastic buttons mostly ended this business when they became more widely available during World War II. Still, Arkansas mussels have been in demand for a different reason. Cultured pearls became in fashion after World War II, and a Japanese entrepreneur discovered using beads from Arkansas mussels could create perfect pearls. He inserted the mussel shell fragments into oysters to create these pearls. From the 1960s to the 1980s, mussels were harvested and shipped to Japan. Fortunately, the trend began to disappear, but the mussel population in Arkansas faces new threats, and they’re still caused by humans.

Threats to Arkansas Mussels

The landscape of our Arkansas waterways has changed considerably in the last 100 years. Rivers have been dammed and lakes formed. These dams have prevented some host species of fish from moving downriver, impacting the mussel populations that rely on them to grow their young. Damming rivers also made it difficult for some species to survive, since mussels thrive in shallow, warm water. Increased sedimentation from erosion has also caused the mussel population to struggle. Soil carried from farms or exposed riverbanks muddy the riverbeds and suffocate the mussels. Chemicals in the soil also erode into the water. These pollutants also harm the mussels.

Another threat to native Arkansas mussels is the introduction of zebra mussels into the waterways. Zebra mussels are an invasive species that originated in Eastern Europe and were carried into the U.S. by ocean-going vessels that entered the Great Lakes. Zebra mussels are much smaller and multiply very quickly. They attach readily to hard surfaces and inundate stream beds, even attaching to the backs of larger mussels. First detected in Arkansas in 1992, they and are present in Bull Shoals Lake, the White River, the Mississippi River, Greers Ferry Lake, the Arkansas River, Lake Conway, the Dardanelle Reservoir and Plum Bayou. To learn how to stop the spread of zebra mussels when fishing, boating, or enjoying the water on Arkansas lakes and rivers, visit the United States Geological Survey site.

Arkansas mussels are found in most waterways, and with names like Arkansas Fatmucket, Turgid Blossom, and Fat Pocketbook, they’re interesting to study and seek out. But the best place for Arkansas mussels is in Arkansas rivers, streams and lakes. If you find live mussels, leave them alone and remember they do their part in keeping our water clean and our ecosystem functioning well.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

Hello. I teach middle school ELA in Wynne, AR. My students read an article the other day about mussels in the Mississippi River. I opened my email this morning to find your story, Arkansas Mussels. I am so excited to share this with my students. I loved the article.

The story reminded me of this place in Malvern Arkansas where I find fossilized shark teeth mussels clams shells and more.. it definitely is amazing how long these mullusks have existed here in Arkansas…

[…] and a post office, drugstores, a lumber factory, and even a button factory that made buttons from mussels gathered in the nearby White […]

[…] needed beautiful, functional buttons made from the mother-of-pearl lining found inside the Arkansas Mussels that were prolific in the Black River. This display dives deep into the fascinating story of […]