Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

We must look for some legislation before long in regard to the pitcher. We are all willing to concede that he is a plucky, determined Base Ball character, and the very fact that he is so persistent and combative makes it necessary now and then to subordinate him a little to the other men who are part of the game.”

— Spalding’s Official Baseball Guide, 1909

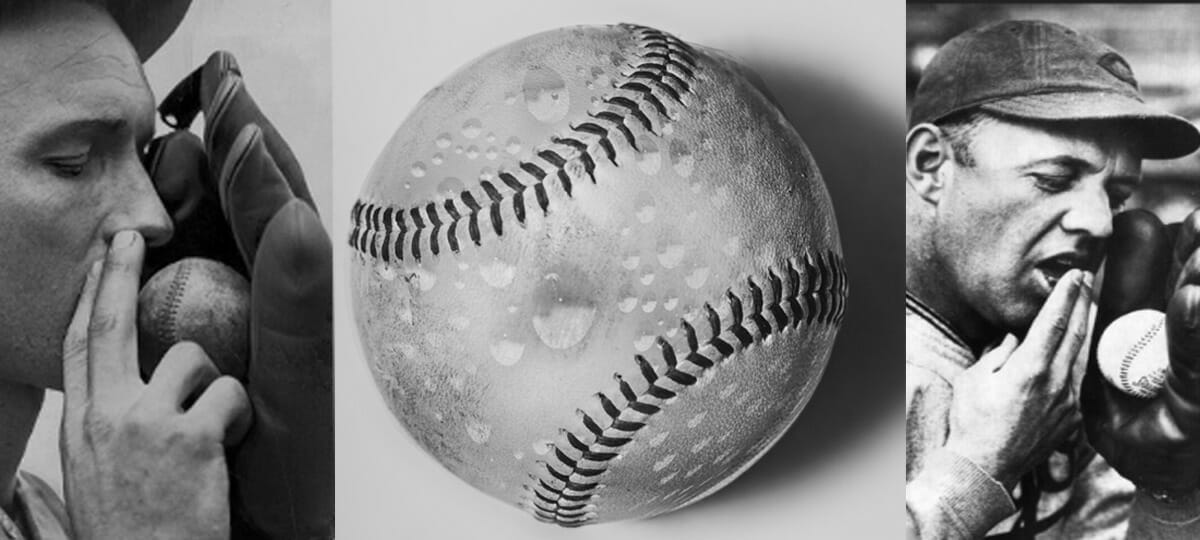

Despite declarations to the contrary, baseball has always clandestinely made pitchers the villain. After all, pitchers initiate every action in baseball and although purists claim to like a one-to-nothing pitcher’s duel, fans, in general, like to see the ball in play or deposited over the outfield fence. Pitchers, by assignment, are formidable enemies of action and are deemed to have sufficient skills without the help of a foreign substance or a vandalized ball. The rules-makers made their first serious attempt to stop the cutting, soiling, scuffing and applying saliva, 100 years ago. They made their last attempt to guard against such mischief in 2021.

Jack Chesbro

“Big Ed” Walsh

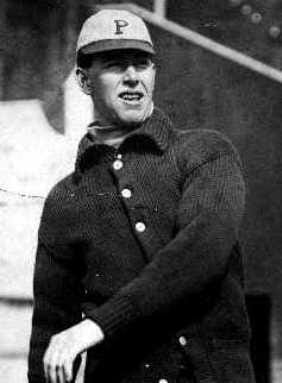

The individual, who first decided to spit on a baseball to see what would happen when it was thrown, is not celebrated as a significant innovator in the game. Perhaps the discovery that salvia, correctly applied, made the ball dart down erratically, was more accidental than scientific. Although the father of the spitball remains uncredited, the first two big-league pitchers to rely on the pitch successfully were Jack Chesbro and “Big Ed” Walsh, who pitched concurrently in the early 1900s and were elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame together in 1946. The first Arkansan to reach the major leagues as a spitball artist was a much-traveled baseball journeyman from North Little Rock named Bill Luhrsen.

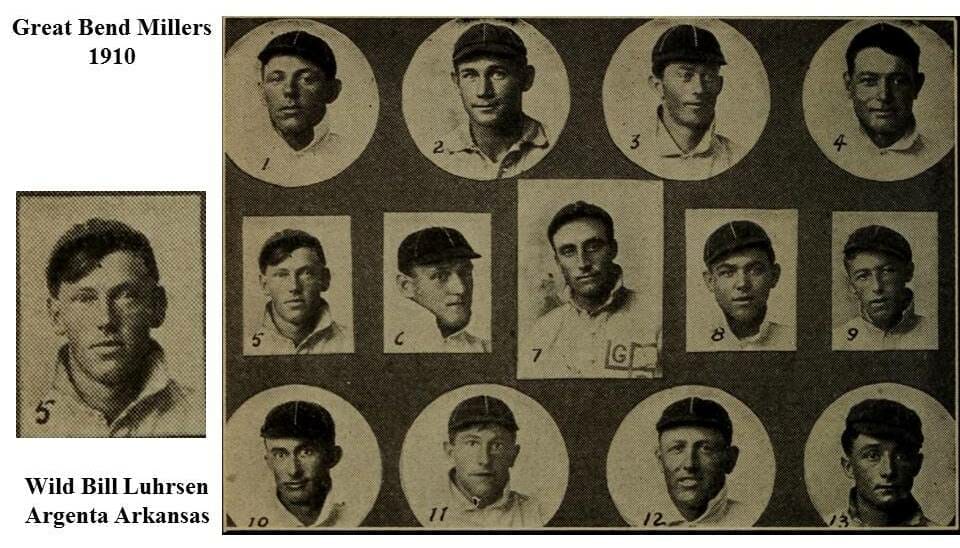

William Ferdinand Luhrsen was born in Illinois on April 14, 1884, but he called North Little Rock, Arkansas, his home all his adult life. By the middle of the 20th century’s first decade, the Luhrsen’s were well known around the little city called Argenta, across the Arkansas River from Little Rock. Bill’s brother Louis was an Argenta alderman, and brothers, Bill and George, were getting noticed as semi-pro baseball standouts. Desperately in need of a baseball nickname, young William became known around ballfields as “Wild Bill” Luhrsen.

Baseball-Reference.com credits Wild Bill Luhrsen with exactly 100 professional appearances, but those recorded games all occurred after 1909 and do not include at least as many games played in the Arkansas State League and the Northeast Arkansas League. From 1906 through 1909, Luhrsen pitched for most of the minor league teams in the small cities in his home state. At various times, Wild Bill was the ace pitcher for his hometown Argenta Shamrocks, and teams in Brinkley, Pine Bluff, Marianna, and the Alexandria, Louisiana, Hoo Hoos, who despite the location, played in the Arkansas State League. In both the 1908 and 1909 seasons, he pitched for three of the above small-town minor league clubs in the same season.

Luhrsen spent seven summers in the fragile world of minor league baseball from 1906 to 1912. In those seasons on the backroads of American baseball, he never started the season with a team that did not cease operations before completing the schedule. Luhrsen and his spitball played in cities from New York to Kansas, and back to Alabama and Georgia, finally reaching the major leagues in 1913.

Honus Wagner

Rube Robinson

Wild Bill started the 1913 season in the low minor leagues at Selma, Alabama, but was promoted in mid-season to the Class C Albany, Georgia, Babies of the South Atlantic League. A month later after a combined 17 – 8 record for the season, Luhrsen got the call to report to the major league Pittsburgh Pirates. Among his teammates in Pittsburgh were Future Hall of Famer Honus Wagner, and Future Arkansas Hall of Fame selection Rube Robinson.

Bill Luhrsen was in fast company, but he continued to pitch well in the big leagues. After two starts and a couple relief appearances, he had won 3 games and lost none, with an Earned Run Average of 2.00. Unfortunately, he was about to meet the greatest pitcher of his day, and receive some shocking news.

In his third start on September 13, Luhrsen faced Future Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. Going against a living legend, in front of a large home crowd, on a Saturday afternoon, may have given Luhrsen a case of stage fright. In the first two innings, he gave up two hits, three walks, and a hit batsman. By the bottom of the second inning, Manager Clarke had seen enough and pinch hit for his rookie pitcher. In fact, despite three wins, only one loss, and a 2.14 ERA, Clarke had decided Luhrsen was not ready for the big leagues.

Wild Bill Luhrsen was traded down to Columbus in the American Association, the highest level of minor league baseball, with a promise that he would return as soon as he worked out some mechanics. Luhrsen never pitched in another major league game. For Arkansas’ traveling spitball pitcher the next two seasons would literally be a train ride through the bush leagues of baseball’s back roads. Even for a man with a history of forced travels, the downhill journey from the major leagues through descending levels of minor league baseball and back to Arkansas semi-pro leagues was a disheartening odyssey.

Preacher Roe

Baseball would officially ban the spitball in 1920, but allow 17 exempted pitchers, who depended on the pitch for their baseball livelihood, to continue to throw the spitter until retirement. Fourteen years after the spitball had been banned, a 40-year-old pitcher for the Pittsburgh Pirates used the last legally-thrown spitball to strike out Brooklyn Dodger journeyman Joe Stripp in a 2 – 1 Dodger victory. The pitcher had a suitable name and the villain’s face to oppose a Kevin Costner character in a Hollywood baseball movie, but the end of the spitball melodrama ended without significant fanfare. The virtually ignored date was September 20, 1934, and a sparse crowd generously estimated at 1,000, at Pittsburgh’s old Forbes Field, saw “Ole Stubblebeard,” Burleigh Grimes, throw the last legal spitball in baseball history.

Grimes was the last active member of the 17 rule-exempted pitchers who were allowed to use the spitball. His retirement in 1934 meant the end of the “legally” thrown spitball. Despite the ban on foreign substances applied to the baseball, clever hurlers continued to throw the spitball or other lubricated versions of the slippery sinker. They generally avoided detection and found new and more cunning ways to hide their intent. The deceitful rule-breakers operated without conscience in a game whose rules always seemed to favor hitters. Among those devious hurlers was Arkansas’ Elwin “Preacher” Roe, who admitted after his retirement that he had thrown a spitball at times. The always clever Roe, also revealed he had more success with a fake spitter. After pretending to go to his mouth, cap, belt, and glove to wet the ball, Roe threw a fastball by the confused hitter.

“It never bothered me none throwing a spitter. If no one is going to help the pitcher in this game, he’s got to help himself.” -Elwin “Preacher” Roe, 1955

On June 27, 2021, Seattle Mariner pitcher Hector Santiago became the first pitcher to be ejected from a game for using a foreign substance under the new umpire-search rule of 2021.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Jim Yeager

Roswell, New Mexico, is a tourist town. The little city on the High...

In 1968, Bob Gibson of the St. Louis Cardinals had what many baseball...

In 1967, Richard Henry Hughes of Stephens, Arkansas, took major league...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment