Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

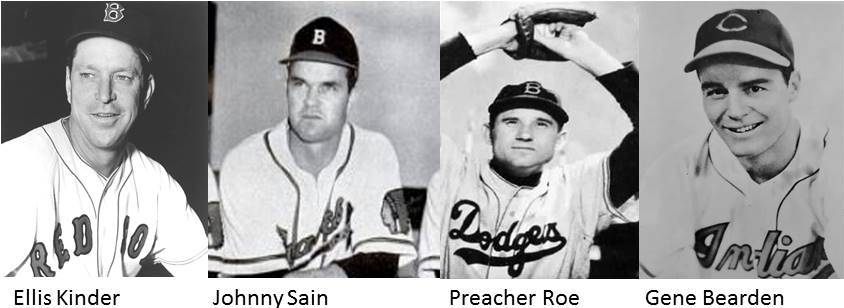

The fourth of four stories about rural Arkansans who became major league pitching stars in the late 1940s

A compelling argument could be made that the key to a successful pitching staff in the late 1940s was to locate the right Arkansas country boy. In 1948, the Cleveland Indians found a knuckleball specialist from the Arkansas Delta named Gene Bearden. Bearden recovered from a catastrophic war injury to lead the Tribe to the American League pennant and a World Series Championship. That same year in the National League, Havana, Arkansas’ Johnny Sain won 24 games, worked more than 300 innings, and pitched 28 complete games for the pennant-winning Boston Braves.

The 1949 season produced a similar story with different characters. Preacher Roe, a part-time math teacher from Viola, Arkansas, won 15 games for the NL Champion Brooklyn Dodgers. He led the team in ERA and the league in winning percentage. Over in the American League, a hard-living 34-year-old right-hander from Atkins, Arkansas, named Ellis Kinder was dominating hitters despite his inattention to any typical training conventions.

Ellis Raymond Kinder was born into poverty in 1914 and raised in the cotton fields of the Arkansas River bottoms. He dropped out of school after seventh grade, and when a devastating drought brought life-threatening starvation to an already impoverished region, Kinder was forced to grow up quickly. By his teens, he dragged his pick sack through the cotton patches alongside the adults. Kinder also joined the local adult men in the Sunday afternoon baseball games. Despite his father’s strict rules against Sunday baseball, Kinder would leave from church and secretly head off to pitch in the afternoon semi-pro games. By evening, after a quick dip in the creek, he was back in his Sunday clothes and back in church.

Kinder was pitching for the Bibler Lumber semi-pro team and working at the company sawmill at Scottsville in 1938 when Hartley Gilland, owner of the Jackson Generals, sent his brother, Preacher Gilland, to offer Kinder $75 a month to become a professional pitcher. It was an offer he could not refuse.

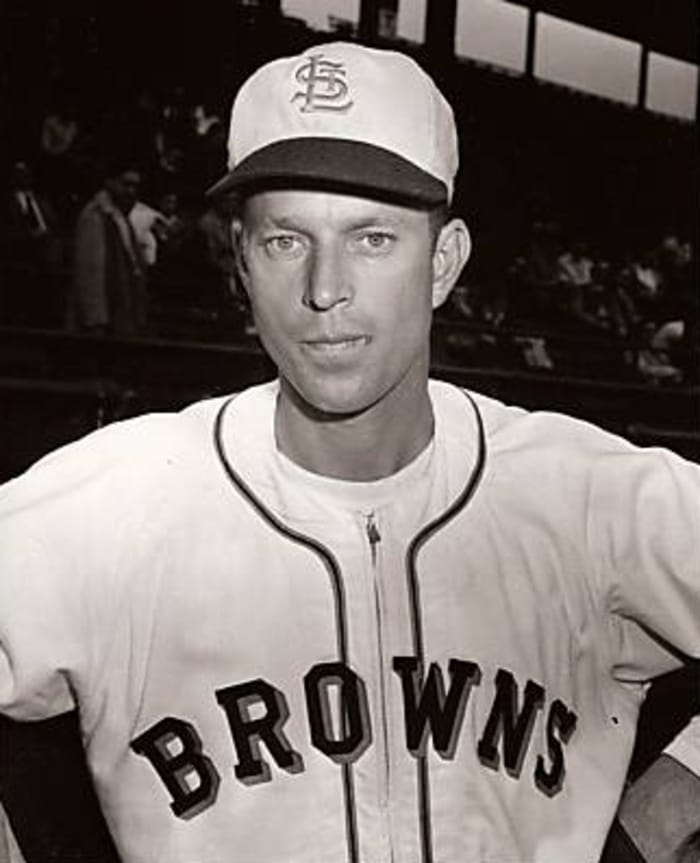

It would take five minor league seasons and a tour of duty in the Navy before Kinder reached the major leagues. He was 31-years-old when he joined the St. Louis Browns in 1946. Eight years older than the average rookie, his teammates called him “Old Folks.”

Like many southern country boys, Kinder arrived in the major leagues with little experience managing big city temptations. Unfamiliar with free time and spending money, they often celebrated when there was nothing in particular to celebrate. Kinder’s wife, Hazel, lamented on his lifestyle with this obviously understated description on the occasion of his induction to the Jackson Tennessee Hall of Fame, “Ellis, bless his heart, did enjoy a good time.”

Sunrise regularly found Kinder still enjoying the activities of the previous evening, often when he was the scheduled starter for that day’s game. Fortunately for Kinder and other rowdy night owls, it was also a time when sportswriters protected players’ personal lives and even enjoyed a special place as the “designated friend” to get baseball stars safely to their rooms after a debilitating evening.

Ellis Kinder had one such friend in renowned sportswriter Arthur Richman. Despite obvious differences in culture, the Jewish city boy and the uneducated country boy from Arkansas became close friends. On one occasion Kinder had Richman accompany him home. When the sportswriter saw the large crowd at the train station, Richman remarked, “Looks like they got a great homecoming for you.” Kinder replied, “Naw, Artie, I just told them I was bringing a Jewish kid with me and they are all here because they have never seen a Jew before.”

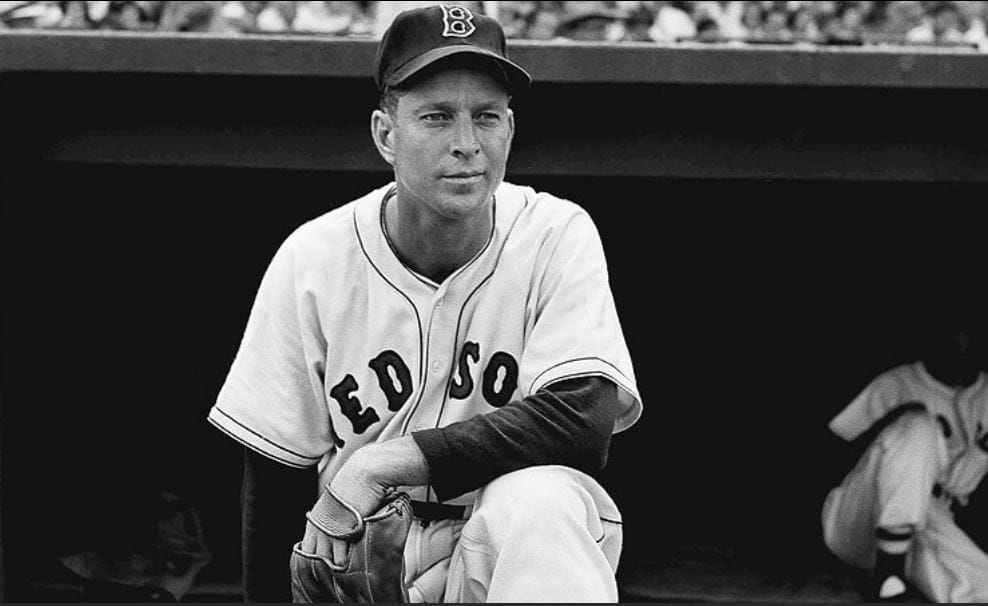

After two lackluster seasons with the Browns, Kinder was traded to Boston in 1948. The Red Sox had the league’s best hitter in Ted Williams, but needed pitching help. They were perennial contenders but seemed destined for disappointing finishes. Kinder arrived just in time to play a part in two of Boston’s most heartbreaking and often second-guessed seasons.

Injured in spring training, Kinder righted himself at midseason and won seven of his last nine decisions. The Red Sox caught the Cleveland Indians on the last weekend of the 1948 season, but Kinder was not chosen to start the one-game playoff. Boston lost the tie-breaker in the first of two tragic endings to a pennant race that fans blamed on Manager Joe McCarthy.

In 1949, Boston’s “wait till next year” hopes were dashed in a similarly tragic ending precipitated by a questionable McCarthy decision. Ellis Kinder was the Sporting News Pitcher of the Year. He posted 23 victories, led the league in winning percentage, and finished ten games in relief, between starts down the stretch. He was the Red Sox obvious choice to start the final game of the season, tied with the Yankees and the league title on the line.

What was not obvious to many Boston fans at the time was the decision to pinch-hit for Kinder in the eighth inning with Boston trailing 1 – 0. Kinder was pitching well, and the Red Sox had two more turns at bat to catch the Yankees. Unfortunately for Boston and McCarthy, the relievers, Mel Parnell and Ted Hughson gave up three runs in the bottom of the eighth. To add to the pain of not having Kinder finish the game, the Red Sox scored three in the ninth, to fuel fans’ conviction that Kinder would have won the pennant for Boston had he remained in the game.

The heartbreaking finishes of 1948 and 1949 were examples of an 86-year saga of close losses and near misses the Boston fans attributed to the trading of Babe Ruth to the Yankees before the 1920 season. “The Curse of the Bambino” would continue until 2004 when the Sox finally won the World Series.

Beginning in 1950, Ellis Kinder reinvented himself, partly as a concession to his age, but primarily due to the emergence of relief pitching as a weapon rather than a concession of defeat. Relief pitchers became an essential part of a complete pitching staff and Ellis Kinder became the best of these new specialists. He started 23 games in 1950, but only 14 the remaining seven years of his career.

By 1951, Kinder was the epitome of the new managerial strategy of calling on a reliable relief pitcher to save a game or hold the opposing team in check. He led the league in pitching appearances, finished 41 of the Red Sox games, and although it was yet to be an official statistic, he led the league with 16 saves.

One particular appearance on July 12, gave relief pitching an epochal credibility boost and elevated Old Folks to hero status in Boston. Kinder took over to start the eighth inning with the score tied and held the Chicago White Sox scoreless for 10 innings. The Red Sox finally scored a run in the 17th inning to win, 5 – 4 in one of the most memorable relief performances of all time. In those two hours of work, Ellis Kinder moved relief pitching to a new level.

Although the Red Sox never made it to the World Series in the 1950s, Ellis Kinder remained the consummate relief pitcher in the game. He saved 89 games in Boston, before a trade to the Cardinals in 1956. Saves became an official statistical category in major league baseball in 1969, and when historians retroactively calculated saves for pitchers before that time they discovered that Ellis Kinder was the only pitcher in baseball history, before 1960, with more than 100 wins and 100 saves.

Kinder pitched in almost 500 major league games, all after the age of 31. Although his formal education ended in elementary school, he is regarded as one of the craftiest pitchers in baseball history. Ellis Kinder died in Jackson, Tennessee, in 1968. A member of the Jackson Generals Hall of Fame, and the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame, he was inducted into the Arkansas Sports Hall of Fame in 1980.

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

3 responses to “Hall of Famer Ellis Kinder, Known as “Old Folks””

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

Hi Jim!!! I stumbled across this by accident, but am so glad I did. Your writing is amazing and the reader can easily relate to your passion about your chosen subject. I adore writing…thanks for the inspiration! Give my love to Susan…I miss y’all!!!

Mr. Yeager, I look forward to these stories every month.

[…] same year and about a mile down the road from the birthplace of future major league pitching great Ellis Kinder. After the flood of 1927 and the Great Depression, the Kinders survived in Wilson picking cotton, […]