Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

I once heard an elderly woman at a baby shower declare, “Everyone should be named after somebody! Our name is our heritage!” This took place during a slightly heated discussion about baby names. It was a learning experience in many ways, mostly because I decided to never, ever, discuss potential baby names at my own future baby shower. But, here in Arkansas, all we have to do is take a drive down a highway, or a stroll across town, to discover that elderly party attendee was correct. Our names are our heritage, and most Arkansas locations are named after someone.

For example, Asher Avenue in Little Rock was named after Judge Joseph Asher. Once upon a time, when there were no major interstate roadways, Asher Avenue was part of the route travelers took to get back and forth between Memphis and Dallas. Dardanelle was named after a French explorer, Jean Baptiste Dardenne. Cantrell Road in Little Rock was named after Deaderick Harrell Cantrell, a prominent Arkansas attorney. Weiner, despite the jokes, was not named over anything hot dog related. It was named after the last name of an engineer who oversaw construction of the St. Louis Southwestern Railroad. Geyer Springs was named after the family who owned a farm in that area, and the springs where travelers stopped to drink. Our state’s name history is fascinating, and today we’ll explore a few of the Arkansas “greats” in place names.

Kavanaugh

I drove Kavanaugh Boulevard in Little Rock for many years on my daily work commute, and it simultaneously pleased and vexed me. The beautiful stately houses were delightful, the winding curves and steep grade? Not so much. It turns out that the geography of Kavanaugh Blvd was planned, as it once had to twist and wind up the hills to accommodate the electric streetcar system (which couldn’t handle a steep grade). These streetcars transported Heights and Hillcrest residents back and forth to downtown Little Rock. This winding road was named after a man whose name was as unique and stately as the houses that line it (although it wouldn’t be named Kavanaugh Boulevard until 1936).

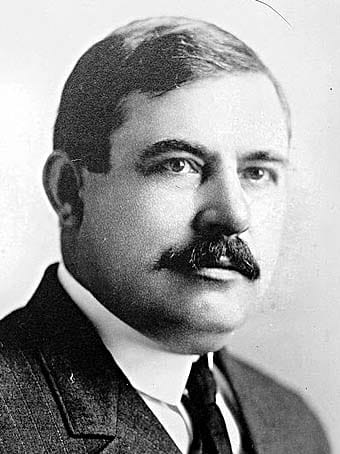

William Marmaduke Kavanaugh was considered to be one of Arkansas’s most important citizens. Born in 1866 in Alabama, he moved to Little Rock in 1886. He wore almost every hat imaginable during his lifetime; serving as president of the Little Rock Railway and Electric Company, treasurer of the Central Heating Company, managing editor of the Arkansas Gazette, Sheriff of Pulaski County, a county judge, not to mention spearheading building the road that led to the Heights (just to name a few). After a lifetime of hard work and dedication to his beloved city and state, he passed away in 1915. Businesses and public schools closed on the day of his funeral.

Beebe

Like so many of Arkansas’s early leaders and statesmen, Roswell Beebe was born in the northeast in 1795. Raised amid wealth in New York state, he went on to fight with Andrew Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans (which is, as a side note, the inspiration for Arkansan Jimmy Driftwood’s famous ballad). After fighting in New Orleans, it appears he stayed there, successfully running a business. Beebe struggled with rheumatism and eventually moved to Little Rock. Temporarily debilitated by his illness, he stayed in Chester Ashley’s home and eventually married Ashley’s sister-in-law.

Beebe ventured heavily into the real estate business and is credited with creating the patent for the town of Little Rock and drawing up the plan for the grids and blocks downtown. He gave land to the city (which would become Markham Street and the land where the new capitol was located). Beebe donated land for a school and cemetery (which would eventually become Mount Holly Cemetery). He was also president of the Cairo and Fulton Railroad Company. Beebe had a good reputation among Little Rock residents and was known to be a fair and honest man.

Upon Beebe’s death, while visiting his childhood home in New York state, the railroad company honored him by naming its first locomotive the Roswell Beebe. They also designated one of their stops, Beebe Station, in his memory. This location would eventually become the town of Beebe.

Ambrose Hundley Sevier, Public Domain

Sevier

Sevier County was named after Ambrose Hundley Sevier. Ambrose hailed from Tennessee. Born in 1801, his mother’s last name was Conway, and his great uncle was a Revolutionary War hero. Sevier settled in Arkansas, where he eventually became a member of the Arkansas Territorial House of Representatives. He married into a powerful political family with connections across the country. This group was known as “The Family” and would go on to dominate Arkansas politics for nearly 200 years.

Sevier and Andrew Jackson were political allies (as were many of Arkansas’s early leaders). He helped secure Aransas’s statehood, viewed the expansion of settlers westward as a right (he supported much of the inhumane Indian removal policies), and supported conflict with Mexico.

After years of political domination in Arkansas and Washington, Sevier suffered some major personal setbacks. He was “censured” for financial malfeasance (a declaration of wrong-doing by a public official) for his ties to a failed bank. A few years after that his wife passed away. He temporarily resigned his seat in the Senate and worked as a commissioner in Mexico, brokering the peace treaty. He became ill there and returned to his plantation in Arkansas. His “fill in” for the Senate won the seat officially in 1848 by a mere four votes. Sevier, who is said to have never recovered from the shock of losing his Senate seat by such a narrow margin, died the same year. He is one of the many political giants buried in Mount Holly Cemetery.

Pope

Pope County was named for John Pope, another colorful frontier Arkansan. Born in 1770 to colonial patriots in Virginia, he lost an arm as a child during a farming accident. He became a lawyer and embarked on an illustrious political career in Kentucky. An outspoken figure, he opposed the War of 1812. After supporting Andrew Jackson’s bid for President, he was appointed the territorial governor of Arkansas in 1829. He enacted policies to make the Arkansas territory more attractive to reputable settlers (it had quite the reputation of lawlessness), even going so far as to be the first territorial governor to bring his family with him to the frontier.

Pope is credited for selecting the site of construction for the Old State House, which is now the oldest surviving state capitol west of the Mississippi. Known for a long-standing rivalry with Robert Crittenden, Pope had a close professional relationship with the Arkansas Gazette and Ambrose Sevier. Pope’s political opinions began to differ from those of Andrew Jackson, and therefore Pope was not appointed as the territorial governor for the third time. He moved to Kentucky, where he served in the House of Representatives. He passed away in 1845.

For more Arkansans Behind the Names, be sure to check out Part I of this series!

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Liz Harrell

My son has a favorite phrase he uses when faced with repetition. It...

I remember visiting my grandmother on her lunch break. She worked at a...

Every time my dad comes to visit me, he reminds me of how small Conway...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment