Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

It only takes a little driving in Arkansas to run across some interesting town and place names that sound French. Arkansas’s history is checkered with forays by European explorers. And the French were the first Europeans to establish a permanent settlement in the territory that would eventually become Arkansas.

Hernando de Soto

The Spanish were the first explorers to set foot in Arkansas. Hernando de Soto arrived in Arkansas with his expedition in 1541. He crossed the Mississippi River into Arkansas on June 28, 1541, and spent the next year roaming the state. De Soto’s expedition was a key point in Arkansas history. He was not only the first European contact the Indigenous populations experienced, but his group of explorers unintentionally brought numerous diseases with them. De Soto described large communities of people living in towns who had the ability to raise an army of thousands if needed. When the French arrived over 100 years later, these populations had been nearly wiped out by diseases like measles, smallpox, influenza and other respiratory infections.

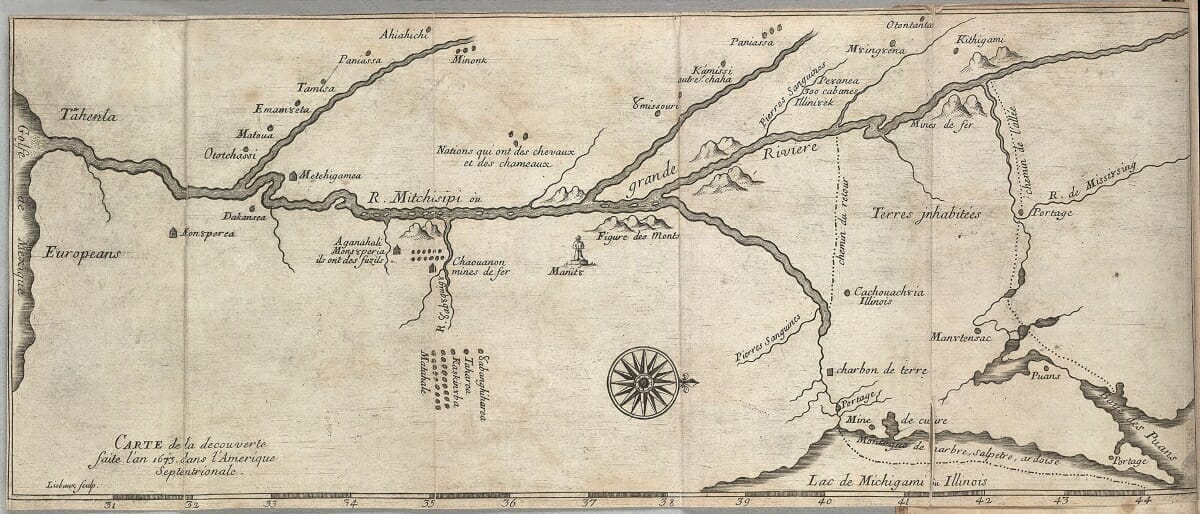

First French to Arrive in Arkansas – Marquette and Joliet

The first two Frenchmen to arrive in Arkansas were Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet. Both were residents of New France at the time, which was the name given to Southeast Canada. Louis Joliet was born in Quebec. He was well-educated and had become a fur trader. The fur trade was the economic driver behind French exploration. It required peaceful interaction with Indigenous peoples, who traded furs with the French for European commodities. His expedition partner, Father Marquette, was a Jesuit priest who had arrived in New France in 1666 and was in charge of a Jesuit mission in what would become Michigan. Marquette had become proficient in at least five Indigenous languages, including Illinois.

The two set out from St. Ignace, Michigan in two canoes with three other men. This small expedition’s purpose was to explore the Mississippi River to see if it led to the Pacific Ocean. They left May 17, 1673, and encountered several villages of Illinois peoples. They reached the mouth of the Arkansas River and were met by members of the Quapaw tribe from Kappa, a Quapaw village. The Frenchmen were the first Europeans in Arkansas in over 100 years. Though wary at first, the Quapaw offered the men food and smoked the calumet, a type of pipe, with them. Marquette wrote in his journal:

A place had been prepared for us under the scaffolding of the chief of the warriors; it was clean, and carpeted with fine rush mats. Upon these we were made to sit, having around us the elders, who were nearest to us; after them, the warriors; and, finally, all the common people in a crowd.”

Marquette kept a detailed journal of the voyage, and added that the Quapaw brought food continually to the men, mostly made from corn, with some watermelon and meat. They spoke of their enemies downstream and discouraged the men from continuing their voyage down the Mississippi. Once Joliet and Marquette discerned that the great river led to the Gulf of Mexico, and not west, as they had hoped, they decided to return to New France. Their initial contact with the Quapaw set the tone for the next French explorer to Arkansas.

Explorer La Salle

La Salle and De Tonti

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (which roughly translates to Lord of the Manor), was another well-educated Frenchman turned fur trader determined to further French exploration beyond New France. Armed with the information Joliet and Marquette had gathered, La Salle wanted to sail down the entire Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico. La Salle was primarily concerned with expanding the reach of French fur traders.

La Salle, along with fellow explorer Henri de Tonti, arrived at the Mississippi River in February 1682, and built canoes for the journey. They reached Kappa and stopped to visit the Quapaw that Marquette and Joliet had established contact with nine years earlier. The Quapaw and the Frenchmen established a relationship that would benefit both groups for trade and protection from the Spanish and other tribes. La Salle then sailed to the Gulf of Mexico.

Henri de Tonti returned to the Quapaw four years later, in 1686. He established a French fur trading post where French settlers could gain a foothold. The post was near the Quapaw village of Osotuoy, at the juncture of the Arkansas and Mississippi Rivers. This post, named “Aux arcs” or “Poste de Arkansea” was the first European establishment west of the Mississippi River. Arkansas Post would remain a trade, government and cultural center until 1821, when it began to decline in importance.

Wood Runners

The French presence in Arkansas continued, but settlers didn’t arrive in large numbers. Instead, fur traders and hunters, mainly French-Canadians, traveled to Arkansas in search of buffalo, beaver and bear. These traders continued the alliance between the French and the Quapaw and learned to live alongside the tribe. These Frenchmen were known as “coureurs des bois”, or wood-runners, and they lived mainly independently of the French government. Though the first French explorers established Arkansas Post, the coureurs des bois are likely responsible for many of the French names that remain in Arkansas.

Once the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory in 1803, French settlement declined over the next 20 years. The Quapaw eventually gave up part of their territory to the U.S. in a treaty, and at the time of the Louisiana Purchase, only numbered around 700 members. As Americans took control of Arkansas, many of the French connections were lost. Today, these connections remain through place names, perhaps most famously through Ozark (Aux Arcs) and Little Rock.

La Petite Roche – The Little Rock

The naming of Little Rock belongs to Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Bénard de La Harpe. He traveled up the Arkansas River in 1722 and noted the rock formations that marked the transition from the delta region to the foothills of the Aux Arcs (Ozark Mountains). La Harpe called the larger rock formations “Le Rocher Francais”. The smaller rock formation was well known in the area, especially by the Quapaw, and called “La Petite Roche” or the little rock. When the Quapaw signed the treaty denoting the borders of their territory, Little Rock was used as a marker of the northern boundary.

Other French names still in use today include Chicot, which means “stump” in French, Saline, meaning salt or salty, and Fourche La Fave. Fourche means fork, as in fork of a river. And La Fave is likely derived from La Fevre, the name of one of the earlier French settlers on the Arkansas River.

Although much of the French history of Arkansas has been lost, you only have to look at the lingering French names to remember Arkansas’s connection to New France, the French-Quapaw alliance, and how the state’s early history influenced its development. To learn more, visit the Arkansas Post National Memorial or Arkansas Post Museum State Park, or read the excellent series of articles over early explorers and European exploration and settlement in Arkansas at the Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Like this story? Read more from Kimberly Mitchell

The XXV Winter Olympics concluded this February in Italy, and one of the...

Scott Fitzgerald never forgot the feeling of freedom he got from biking...

Trains revolutionized the United States in the 1800s. People and goods...

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment