Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

Secreted away beneath the waters of Beaver Lake in Northwest Arkansas lie the remains of William Hope “Coin” Harvey’s community of Monte Ne. Much like the mystical town of Brigadoon, the resort established in 1901 now only appears when the conditions are right. In the instance of Monte Ne, a once thriving destination sought after by travelers looking for respite in the cool of the spring-fed valley, those conditions happen to be when the water level on Beaver Lake is low.

However, unlike the town of Brigadoon, there are some structures of Monte Ne that you can see at any time. Those structures include the tower that was once a part of Oklahoma Row Hotel–often mistakenly referred to as the honeymoon tower–and a four-sided chimney with fireplaces that once served several rooms in the Missouri Row hotel. These haunting vestiges are reminders not only of days gone by, but also of a larger dream unrealized.

Monte Ne origins

Coin Harvey was a teacher, lawyer, developer, silver mine owner, author, entrepreneur and promoter from West Virginia. He was most well-known during his time for writing “Coin’s Financial School” about the virtues of silver. His book was incredibly popular, a bestseller that was second only in sales to the Bible; however, his ideas about the silver standard eventually fell flat. After coming through the Ozarks while stumping for William Jennings Bryan, the 1896 Democratic presidential nominee who campaigned on a silver platform, he was so taken by the area that he decided to purchase some land. There’s no clear indication of why Harvey chose this area, but Allyn Lord, director of the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History and author of “Historic Monte Ne,” points out that the Ozarks likely looked quite similar to his home state. At first, he only purchased a small parcel of land, but after the defeat of Bryan to William McKinley, he returned and purchased 300 more acres in the Ozarks to build the resort he came to call Monte Ne.

From the very beginning, Monte Ne resort was a place for vacationers to gather, be entertained, and to see and be seen. Especially for those traveling from cities and towns along the Frisco railroad line, it was the place to be. The resort was home to the very first indoor swimming pool in the state and one of the first golf courses. It was also advertised as “The only place in America where a gondola meets the train.” Harvey had a railroad station built and put in a five-mile railway spur that brought travelers from the transfer station in Lowell to Monte Ne. Once they stepped off of the train, they were met by a gondola that took them across the lagoon to the hotels. In addition to importing the Italian gondolas that helped create this grand first impression of the resort, Harvey brought in bands and speakers for entertainment and hosted fox hunts and boating and fishing outings. It’s not hard to imagine why travelers sought this resort.

They came, now build it

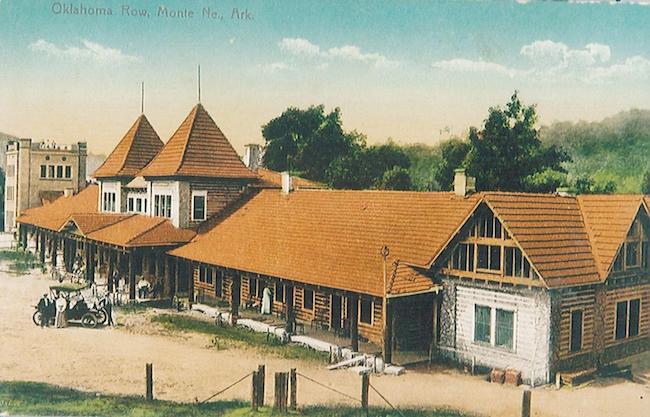

The first building to be erected for the resort was the Hotel Monte Ne, a framed structure with three stories and a large, wide porch or promenade. The grand opening for the Hotel Monte Ne was held in 1901. People began coming out to the resort, and Harvey quickly realized that he needed to build more and add a train station. This led to him contracting architect A.O. Clarke from St. Louis to build the remaining hotels and buildings. At that time, the intent was first to build what would be the Arkansas Hotel in the middle of the resort and surround it with hotels named after the states surrounding Arkansas. Only the foundation of the Arkansas Hotel was laid before worker strikes prevented it from being completed. Harvey had A.O. Clarke then moved on to building the first large log hotel, Missouri Row. According to Lord, the logs that graced the building were purchased from Van Winkle Hollow, the homestead that is now located within the confines of Hobbs State Park. Oklahoma Row was built next in a similar style with logs, Portland cement and a tiled roof, but with the notable difference of the added cement tower. The two hotels were the largest log buildings in the world at the time that they were built, another claim to fame for this infamous resort.

All roads lead to Monte Ne

Ever looking ahead, Harvey saw the writing on the wall with the advent of the automobile and began working to improve the roads that led to Monte Ne. In 1910 he spoke of bringing a network of routes into Arkansas that could be driven by modern automobiles. Then, in 1913 he established the Ozark Trail Association to promote the building of better roadways. His promotion of this idea was always about bringing the most travelers to Monte Ne. He admitted that his interest in the Ozark Trails was mainly that, “they all lead to Monte Ne.”

Despite Harvey’s work to further develop the infrastructure leading to Monte Ne, by 1920 the resort as it had been was no longer. With less costly automobiles and better roads, travelers were not constrained by destinations only accessible by train. They could travel by car, camp along the roadside and then continue to their next destination. While they still stopped in at resorts like Monte Ne, they no longer stayed for the long lengths of time.

Resort declines, Pyramid on the rise

During the 1920s Harvey was met with more setbacks including failing health, the decline of the resort, and the financial difficulties including foreclosure on some of the resort’s buildings. As before, Harvey found a way to move on with a new idea. This time his idea was to build a pyramid that would include a message for the future after the ruination of civilization. Harvey believed that when civilization ended, the mountains around Monte Ne would crumble into the valley and that the tall spire of the 130-foot pyramid would still be visible. According to “Historic Monte Ne,” once those who discovered the pyramid dug down into the base of the pyramid they would find “Harvey’s own books explaining 20th-century civilization, as well as a world globe, a Bible, encyclopedias, and newspapers, all printed on special paper and hermetically sealed in glass. In a large room at the Pyramid’s base were to be placed ‘numerous small items now used by us in domestic and industrial life, from the size of a needle and safety pin up to a victrola [record player].’”

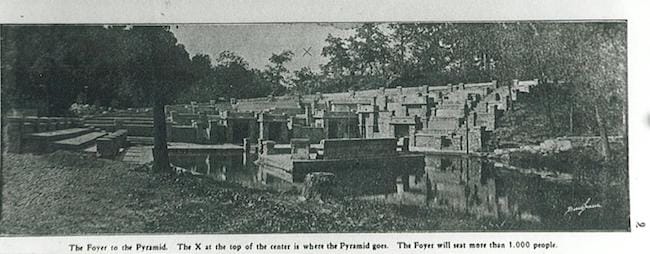

Harvey’s pyramid never came to fruition, partially because Harvey depleted his funds during the construction of the pyramid’s foundation/foyer and entrance room or the amphitheater as it came to be known. Though it was to be used as a way to shore up the pyramid, the amphitheater was constructed without an architect or any blueprints or designs. The outcome of this building method was an irregular, but unique structure. According to “Historic Monte Ne,” the amphitheater averaged 20 feet high and 140 feet long and could seat anywhere from 500-1,000 people.

The amphitheater had the same fate as much of Monte Ne. However, before it was forever buried beneath the waters of Beaver Lake, it was the site of parties, picnics, plays and a site to take in speakers, bands and other entertainment. Most notable of all, the only presidential convention to be held in Arkansas was convened there in advance of the 1932 presidential election. Harvey ran as a candidate for the Liberty Party, a party that he formed with monetary reform as the platform. He gained only 53,425 votes and came in fifth.

What’s Left of Monte Ne?

After Harvey’s death in 1936, he was buried in a tomb that had been built in 1903 for his son. The tomb was reopened, and Harvey was laid to rest with copies of his books and other papers. In preparation for the filling of Beaver Lake, the tomb was moved to private property that can be viewed from the boat launch at Monte Ne.

In their land survey, the Corp of Engineers mistakenly calculated that the property the three hotels stood on would be under water as well, so they purchased the land and dismantled the hotels. Now all that is left standing at the site of the former resort is the foundation and basement of Oklahoma Row, and a fireplace, chimney, foundation and a retaining wall from Missouri Row. When the waters of Beaver Lake are low, you can venture inside the basement of Oklahoma Row and even view part of the foundation of the uncompleted Arkansas Hotel. When the waters recede during times of drought (typically in late fall or winter), part or even all of the amphitheater can arise from the waters again.

Apart from the ruins of Monte Ne, the Rogers Historical Museum holds some relics from the resort for those interested in the history. There you can see many items, including a cement chair that was once part of the amphitheater, a wooden model of what the pyramid would have looked like, and Harvey’s death mask–made by a funeral home employee while waiting for Harvey’s tomb to be ready. At the time of this writing, the Roger’s Historical Museum is closed for construction, but the expanded museum is set to reopen in December 2018.

Directions to the Monte Ne ruins:

The following are directions for getting to the amphitheater which you can only view when the lake level is below 1,111 feet. To determine the current lake level, go to http://beaver.uslakes.info/Level/Calendar/2018/05/

- In Rogers, turn onto New Hope Road (Hwy. 94) going east

- Continue east on Hwy. 94. After a few miles the road will bend sharply to the right (and become Monte Ne Rd.); continue down into the valley.

- About a mile and a quarter beyond the big curve to the right (south), on the left is the log structure of old Oklahoma Row (opposite Rolynn Drive).

- About 0.4 miles further, take a right onto Canal Street and pass Pyramid Drive on the left.

- About 0.7 miles on the left is a dirt road (opposite Summit Drive) with a “Road closed; lake ahead” sign. From here you gain access to the shoreline and the location of the amphitheater.

- Walk east along the shoreline – be aware that, except for the shoreline, the rest of the land is private property – and walk around a small spit of land jutting out into the lake. Just at the edge of that spit of land is the Monte Ne amphitheater, IF the lake level is below 1,111 feet. (Directions courtesy of Allyn Lord).

To get to the other structures of Monte Ne, take the same route above, except continue on Hwy 94 E instead of turning onto Canal Street. Once you begin to see the lake on the right, pull in at the first parking area on the right to view the tower and the foundation of Oklahoma Row. From there you can walk towards the boat launch to view the fireplace and chimney, other foundations and retaining walls, or you can drive down to the parking lot nearest the boat launch. Most of the foundations can be viewed when the lake level is below 1,113 feet.

A casual weekend outing on Beaver Lake seems unassuming enough unless the waters are low and the ghosts of Monte Ne emerge, demanding the viewers’ attention to the long-forgotten (and often misinterpreted) history buried underneath the waters.

As quoted in Lord’s book on Monte Ne: Harvey wrote, “Think of stepping from a train into a gondola. Whoever heard of such a thing in this lakeless island region of the southwest! It’s enough to make one rub one’s eyes and wonder if the glistening water and picturesque craft are real. Think of all the resorts you’ve ever seen or heard of. Picture the hot, dusty ride from the railway station to the hotel. (That will not be difficult.) Then compare the way they do at Monte Ne–a few steps across the platform, a comfortable seat in a gondola or launch and a dustless, joltless ride over a half-mile stretch of cool, transparent water, alighting close to the veranda of a modern, well-equipped hotel. Does it sound like a fairy tale?”

Indeed, it does.

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

2 responses to “Monte Ne: Arkansas’s Underwater Resort Revealed”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

What all places r there to visit

[…] Betty Blake was born in 1879 in a community called Silver Springs, located just south of Rogers. History buffs and Beaver Lake visitors may know Silver Springs by its later incarnation, Monte Ne. […]