Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

Cotton Plant is not an Arkansas town on most people’s radar. It registered just under 600 people in the last census. While it used to be a cultural center for Woodruff County, it’s now primarily a historical context for the region.

While early settlers came at the beginning of the 1800s to hunt unsettled lands, a farmer in 1846 showed up with a handful of cotton seeds he’d brought from Mississippi and established significance for this small town.

During the Civil War, many eligible residents joined the Confederate Army, and the region saw significant military interaction when 5,000 Confederate troops met 20,000 Union troops in the Action at Hill’s Plantation. This interaction between Batesville and Helena was a substantial win for the Union army.

The Encyclopedia of Arkansas tells the story we expect to hear of this location being a cotton exchange and production hub. With a rail line established in 1881, businesses grew and by the late 1890s, “the town shipped 1,500 to 2,000 tons of cottonseed and 4,000 to 7,000 bales of cotton. By 1920, the town had four cotton gins, a cotton compress and several large warehouses.”

While the area became a significant cultural hub for musicians and artists in the early 1900s, the Great Depression shifted everything as the price of cotton dropped, closing several mills and financial institutions. In addition, school integration moved several families to nearby towns, and the population continued to decline.

But history paints a different picture for a few people who once called Cotton Plant home.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe

“Sister Rosetta” Nubin Tharpe is notable for several firsts.

- One of gospel music’s first superstars

- The first gospel performer to record for a major record label

- An early crossover artist from gospel to secular music

- Attributed to influencing the music of Bob Dylan, Little Richard, Elvis Presley, and Johnny Cash

Tharpe grew up in a musical home. Her mom was a singing evangelist and mandolin player, and her exposure started early. By age six, she was performing with her mom, known for holding pitch and playing the guitar as a teenager, when African American women did not play that instrument.

Blues music, hymns, and jazz were all parts of building her musical legacy. Tharpe moved to New York in the 1930s and signed with Decca Records. Through the studio, she released “smashing hits” that gained instant success with gospel and secular artists. Her popularity grew into the 1950s and 60s when she tried anything to connect with new audiences.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe is a member of the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame, the Arkansas Entertainers Hall of Fame, and the Rock ‘n Roll Hall of Fame. In addition, Tharpe was an essential character in the 2022 box office hit Elvis. And last October, a mural in downtown Little Rock was dedicated in her honor.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe is a crown jewel from Cotton Plant, and her legacy continues to influence musical culture.

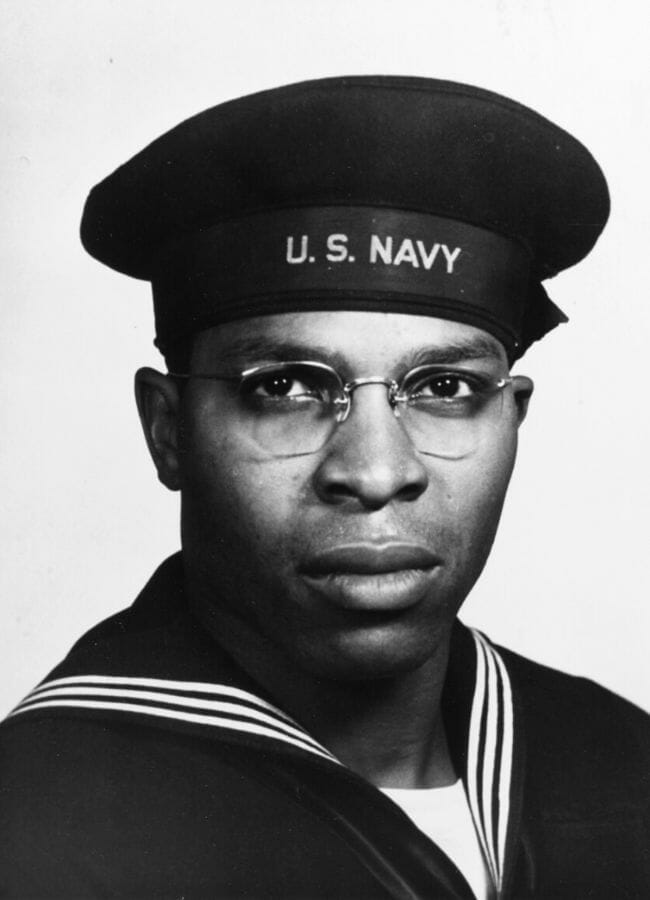

National Archives, public domain.

Jesse Walter Arbor

While the Army desegregated early with its first black General by World War II and the first black West Point officer graduate in 1877, the Navy did not follow suit. Enlistment to blacks was suspended from 1919 to 1933 and denied entry for many even as WWII began. They refused to train these men in technical roles like electricians or mechanics, and they could not advance into ranked officer roles.

It wasn’t until 1941, when President Franklin Roosevelt signed Order 8802 to prevent racial discrimination in government agencies, that anything began to budge. Three years later, with additional pressure from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and the Assistant Secretary to the Navy, an officer training course began for 16 black men. The men were selected from various backgrounds and deeply vetted through the FBI, which was not typical for their white counterparts.

Rather than create a competitive environment, the men banded together from the beginning. They shared stories and built a training system based on each other’s strengths, weaknesses and areas of expertise. They were determined not to be the last black naval officers.

Photo used with permission from Explore Pine Bluff.

Amid a setup to ensure they failed, a condensed and more rigorous training schedule, and studying late at night with flashlights, all 16 men passed their test twice, with a 3.89 collective class average. This score is still the highest average for any Naval training class.

In March 1944, the Navy commissioned 12 men as officers, with one more set as a warrant officer. Among the group was Cotton Plant native Jessie Walter Arbor. The group became known as the Golden Thirteen, the first black men commissioned and warranted as Naval officers. While attention is usually offered to the Tuskegee Airmen or Patton’s Panthers, these men were courageous trailblazers while fighting in a war on equality abroad, with civil unrest at home.

Arbor was honorably discharged from the Navy in 1946 and stayed in the reserves until 1954. During his lifetime, he received the American Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal.

Others to celebrate from Cotton Plant

- Florence Beatrice Price – first African-American woman recognized with a symphonic composition played by a major orchestra

- James McElroy – professional basketball player from 1975 – 1982

- Peetie Wheatstraw – influential blues singer in the 1930s, some called him the spiritual ancestor of rap artists

- Pearl Peden Oldfield – first female elected to Congress from Arkansas

- Benjamin Frank Adair – a prominent black criminal attorney in the 1890s, elected to the Arkansas General Assembly

- Rev. Frank C. Potter – principal of the Cotton Plant Academy, the first Presbyterian school for freed slaves in the South

- Moses Aaron Clark – Arkansas’s first black Justice of the Peace and the most influential black Masonic leader in Arkansas

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

One response to “Deep-Rooted Legacies in Cotton Plant”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

[…] Oldfield grew up near Cotton Plant as the daughter of farmers. She attended grade school locally and Batesville for high school. She […]