Uh oh...

It appears that you're using a severely outdated version of Safari on Windows. Many features won't work correctly, and functionality can't be guaranteed. Please try viewing this website in Edge, Mozilla, Chrome, or another modern browser. Sorry for any inconvenience this may have caused!

Read More about this safari issue.

There are stories in my family about my great-grandfather running afoul of the law when Arkansas was a wild place to live and the United States as a whole was wrestling with calls for prohibiting the sale of alcohol. Campaigns for prohibition were common in the 1800s, and in Arkansas, the push for limiting or completely outlawing the sale of alcohol was steady, but the state didn’t pass a prohibition law until 1915. Moonshining was already common, as my great-grandfather Joe Ross could attest to, but Prohibition made things more interesting. For 16 years, Arkansas was legally dry while plenty of liquor still ran through the state illegally.

Early Prohibition Efforts

Limiting the use of alcohol in Arkansas can be traced to even the earliest Arkansas settlement. When Arkansas Post, the territory’s first European settlement, was occupied by the Spanish, they sought to limit and prohibit sales of alcohol to the Quapaw tribe. Alcohol sales to Native American tribes was a thriving business. In Fort Smith in the early 1830s, the sale of alcohol to Native Americans living in Oklahoma Territory was so common that a commander from the fort organized a sting operation to try to stop sales.

Alcohol was ingrained in people’s daily lives and in Arkansas politics, but public opinion was beginning to shift. In the 1820s and 30s, a religious revival was also sweeping the nation. Churches in Arkansas began to organize members to advocate for a ban on hard liquors. As Arkansas looked toward statehood in 1836, a temperance movement began to grow. Temperance clubs like the Little Rock Temperance Society were formed. The Arkansas General Assembly attempted to curb the sale of alcohol in the state in the 1850s by passing an initiative that was largely ignored. In 1855, they tried again, this time handing more power to municipalities to approve the establishment and licensing of taverns within their city or county limits. The initiative required that a majority of the township approve the licensing and it was a more effective way to limit the sale of alcohol.

During the Civil War, the state banned the production of alcohol in distilleries, but the consumption of alcohol continued, along with growing illegal production. Moonshining, already common in the state, increased. Secret stills sprang up around Arkansas where locals produced mostly corn whiskey. The wildness of the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains made these areas perfect for hiding illegal alcohol production. Farmers realized they could make much more by selling their corn to moonshiners than by taking it to market.

Moonshine Wars

Ben F. Johnson III wrote in his 2005 book “John Barleycorn Must Die: The War Against Drink in Arkansas,” that “in the 1890s a southern farmer could make about $10 when he hauled his 20 bushels of corn to town, whereas distilling 40 bushels into 120 gallons of whiskey could clear $150, without the federal tax.”

The post-Civil War period from the 1870s to the turn of the century was marked by the moonshine wars. U.S. Marshals accompanied federal revenue agents searching for illegal stills in the hill country of Arkansas, as well as across the South. Local law enforcement often landed on the side of moonshiners, either imposing light penalties on captured moonshiners, or even prosecuting revenue agents for injuring moonshiners. Moonshining at this time wasn’t without peril. In 1897, a federal marshal and another man were killed after approaching a still in Searcy County. My grandfather was involved in the moonshine wars as well. He was eventually arrested on charges of illegal distilling and accused of murdering a U.S. deputy marshal as well.

While the moonshine wars raged between local moonshiners and the U.S. Marshals and federal revenue agents, the push for temperance and prohibition increased. The violence surrounding the stills, moonshiners, and marshals during the moonshine wars also encouraged towns to do something to curtail moonshining, as well as illegal sales of alcohol. John T. Burris of Russellville rose to prominence as a deputy revenue collector. In one year, Burris covered 22,000 miles of terrain, captured and destroyed 101 distilleries and arrested 141 men, according to the Arkansas Democrat paper. Coincidentally, one of these arrests was made on another of my southern Arkansas relatives’ land when Burris and his deputies used Duckett Ferry to cross the Cossatot River in search of some known moonshiners. In all, Burris closed over 150 stills and investigated many more, often posing as a timber buyer to entice moonshiners to meet with him.

Two laws in the 1870s helped curtail the legal sale of alcohol in the state and likely contributed to the increase in moonshining. The first prohibited the sale of liquor within 3 miles of educational institutions and the second called for towns to hold referendums every two years on whether or not to allow the sale of alcohol in small quantities within city jurisdictions. This severely limited the operation of saloons. The Arkansas chapter of the Anti-Saloon League was founded in 1899, and the move toward prohibition gained steam. Saloons continued to close as the state greeted the 20th century.

Prohibition Efforts at the Turn of the Century

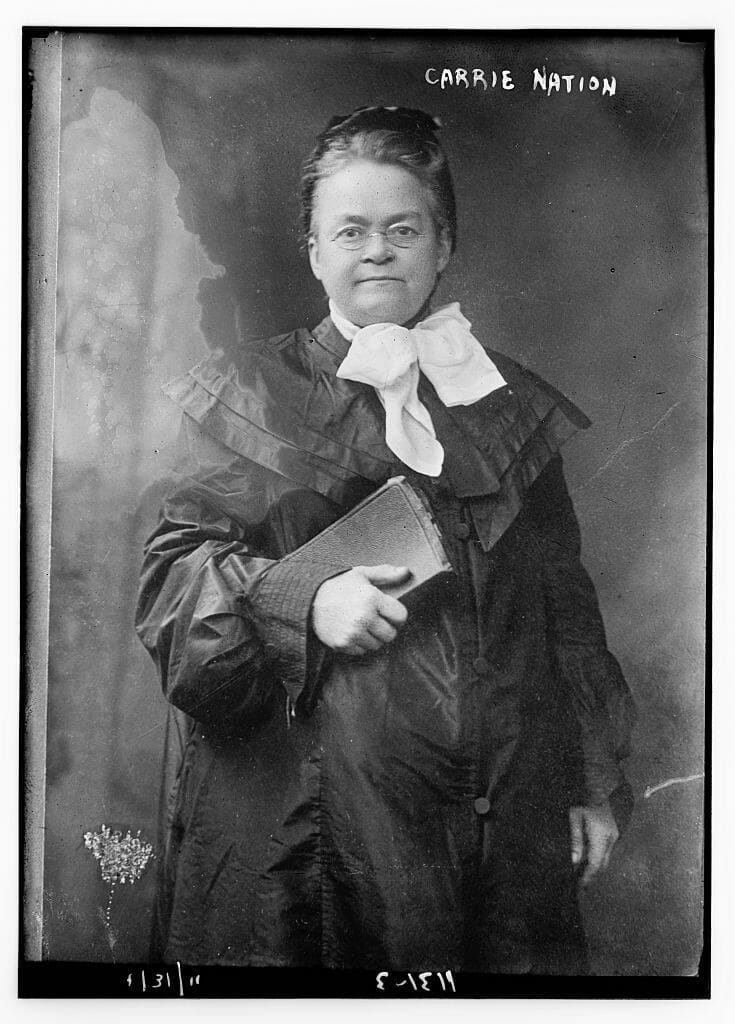

Prohibition advocates also traveled the country. One of the most famous, Carrie Nation, bought a house in Eureka Springs and lived there a short time. Nation was famous for her zeal against anyone who sold alcohol. She carried a hatchet and destroyed bottles of alcohol and kegs of beer in shops. She was arrested many times and spent some time in jail in Little Rock. However, the mayor released her when she agreed to give a speech at the opening of a new subdivision. Nation gave her last speech in Eureka Springs in January 1911, when she fell ill in the middle of it. She died later that year.

In 1915, the Arkansas General Assembly passed its most significant prohibition law, called the Newberry Act. The bill banned the manufacture and sale of alcohol in the state. By this time, only 12 counties in Arkansas were still “wet counties” which allowed the sale of alcohol. Through the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the other counties had all already passed legislation to become “dry counties.” The last of the saloons went out of business. In 1917, the importation of alcohol was also banned, making Arkansas completely dry two years before the 18th Amendment to the Constitution went into effect on January 17, 1920, making prohibition a national law.

Of course, alcohol was still available. Moonshining, now commonly known as bootlegging, survived and thrived all over Arkansas. Most bootleggers were farmers who also had a still as a side business. It was so common that everyone was likely to know at least one bootlegger, if not more. My great-grandfather, who was bootlegging in Polk County, wasn’t the only one hiding a still in the Ouachitas. Other areas around the state well-known for bootlegging were Yell and Montgomery counties, Pope County within the Ozark National Forest, the White River bottoms in Woodruff County, and Garland County, where Hot Springs provided ample opportunities to sell alcohol to visitors, where some of the most infamous were Al Capone, Frank Costello, and many more gangsters involved in illegal gambling and illegal drinking. Capone was also an important connection for Arkansas moonshiners as the mob boss purchased the moonshine and smuggled it out of state.

Prohibition Ends But Its Legacy Endures

Prohibition didn’t reignite the moonshine wars in Arkansas, though, and the state didn’t experience the same type of violence and criminal activity Prohibition produced in other areas of the country, most notably Chicago. Although bootleggers in Arkansas were still arrested for producing illegal alcohol, the arrests often didn’t have the same violence they’d held in the 1800s. When south Arkansas experienced an oil boom in the 1920s, alcohol was even sold openly.

The enthusiasm for Prohibition started waning by the late 1920s. The law was difficult to enforce and had increased illegal activities, including bootlegging and the existence of “speakeasies” or hidden clubs where alcohol was sold. It also began to cost the federal and local governments more to pursue bootleggers and hold them in jail. When the Depression hit, it was the final blow to the existence of Prohibition. A law that was nearly 100 years in the making only survived 14 years nationally, and 16 in Arkansas. On July 18, 1933, a majority of Arkansans voted to repeal Prohibition.

Although alcohol was once again legal in the state, not every county embraced the sale of liquor. The law that allows each county to vote on its own alcohol sales still exists. After Prohibition, many counties elected to remain dry counties. This created a patchwork effect of wet and dry counties across the state. Currently, 34 counties in Arkansas are dry counties, and alcohol sales are illegal statewide on Sundays, with some exceptions. The effects of Prohibition in Arkansas 100 years later are still apparent in these practices and the local laws that guide the sale of alcohol. It is still illegal to produce moonshine (whiskey) without a license from the state or to use a private still to produce moonshine, just as it was when my great-grandfather was moonshining in the Ouachitas.

As for great-grandpa Ross, he served a light jail sentence for moonshining, and the charge of murder was dropped, or at least never pursued. He eventually turned to the other side of the law and became a lawman, father, grandfather and great-grandfather, which leaves me to tell his part in the story of Prohibition in Arkansas.

Join the Conversation

Leave a Comment

2 responses to “The Long Road to Prohibition in Arkansas”

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

We do the work.

You check your email.

Sign up for our weekly e-news.

Get stories sent straight to your inbox!

Leave a Reply

Leave a Reply

[…] when many people advocated for social, political and economic reforms. These included pushes for Prohibition, Women’s Suffrage, and a greater focus on social reforms and […]

you might add that “Goose Tadum” ( basketball player) was born and raised in Calion, Ark.. Nothing to do with whisky!!! ha

— Globe Trotters